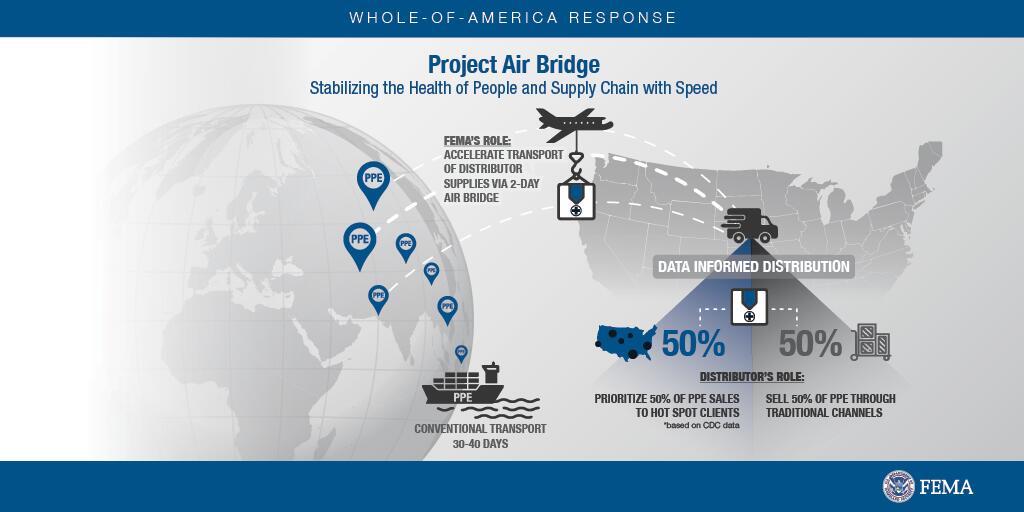

On March 29, President Trump held a press briefing to tout “Project Airbridge,” the administration’s new effort to organize and pay for airlifts of personal protective equipment and other medical supplies from abroad. The first of Project Airbridge’s “big, great planes” coming from Asia had landed in New York that day, Trump said, bringing in “2 million masks and gowns, over 10 million gloves, and over 70,000 thermometers,” which would be distributed to virus hot spots across the country. The heads of some of the country’s biggest medical supply distributors joined him at the podium to pay tribute to the administration and talk about the project. “They’re big people,” Trump declared of the executives working together with the administration to deliver “record amounts of lifesaving equipment.”

The origins of Project Airbridge lie with MIT experts, who originally proposed a government led and funded airlift of supplies, according to the Washington Post. But it was seized upon by Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, who ran a volunteer shadow coronavirus task force that included his former roommate and people from private-equity companies and consulting firms like McKinsey. (“Young geniuses” Trump called them.) Unhappy employees at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) dubbed them “the children.”

Yet less than two months later, after many glowing PR hits, the administration decided to put an end to Project Airbridge as members of Congress and the media started demanding answers about how the supplies were being distributed, who received them, and whether the White House was making distribution decisions based on politics rather than public health. On April 21, 10 Democratic senators, led by Elizabeth Warren, asked the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services to investigate the project. “The novelty and complexity of this arrangement demands heightened scrutiny and transparency,” they wrote in a letter. “However, the administration’s implementation of Project Airbridge has been completely opaque.”

The short-lived Project Airbridge is an example of how the Trump administration has taken advantage of the pandemic to boost some of the country’s biggest companies while doing little more than offer hard-hit states photo ops and the chance to compete against each other to pay exorbitant prices for PPE. And while the project did little to ameliorate national shortages of PPE, it may have a lasting impact on everything from health care costs to the consolidation of corporate power.

The companies involved in Project Airbridge are some of the biggest in the world, including McKesson, Cardinal Health, Medline, and Henry Schein. They are the huge intermediaries of the health care system, distributors of prescription drugs and medical supplies, which they buy from wholesalers and then sell to hospitals, clinics, and government agencies. Yet through Project Airbridge, the Trump administration gave these enormous firms a sweetheart deal free of much if any oversight.

Ostensibly run through FEMA, Project Airbridge arranged for FedEx and UPS to airlift PPE and other medical supplies from Asia to the US in just a couple of days, as opposed to the 30 or 40 days cargo ships require. Through the public-private partnership, the supply companies were supposed to sell half the goods to virus hot spots as determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The other half they got to sell to existing customers or elsewhere on the private market. These taxpayer-funded cargo flights saved the companies at least $91 million in shipping costs, the Washington Post found—savings the administration did not require them to pass on to hospitals or states buying their products. But the perks of Project Airbridge didn’t end there.

In normal times, collaboration between companies that dominate such a large share of the market could trigger a federal antitrust investigation. But the administration gave big distributors a pass on some enforcement of antitrust laws while they worked on the project. Those are fair trade measures designed to prevent big corporations from engaging in anticompetitive practices, such as price fixing, bid rigging, or conspiring to push smaller competitors out of the market. In early April, the Justice Department said it would allow the companies to collaborate because of the extraordinary demands of responding to the coronavirus pandemic. When assistant attorney general for the antitrust division (and former Google lobbyist) Makan Delrahim approved the antitrust waiver, he indicated that the companies would be helping HHS to “understand competitive prices for these supplies and medications” and “negotiate competitive prices.” The companies pledged not to engage in “profiteering,” although DOJ never said how it would ensure that didn’t happen.

Laura Alexander, vice president of policy at the American Antitrust Institute, says the arrangement is troubling. “The very companies that [sought] permission to engage in coordination are those that have a long history of anticompetitive conduct and anticompetitive collaboration,” she says.

Yossi Sheffi, director of the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, told me that the basic premise of Project Airbridge was a good one because the companies have huge networks and reliable sources in Asia. But he acknowledges it may lead to more corporate consolidation. “I think it’s a classic case of efficiency fighting corporate justice,” Sheffi said. “In the good, nice world it would be that every supplier would get their part.”

One solution would have been for the government to take a much bigger, centralized role by purchasing the supplies so states, cities, and hospitals weren’t forced to bid against each other to buy them from those big companies. The Trump administration refused to do that. “We’re not a shipping clerk,” Trump said 10 days before the federal government began subsidizing cargo flights from Asia. As a result, PPE supply chains are still plagued with shortages, high prices, and scammers. In early April, the Society for Healthcare Organization Procurement Professionals found that the cost of an N95 mask had soared 1,513 percent from pre-pandemic prices. The cost of an isolation gown went up 2,000 percent higher.

In addition, the Trump administration has refused to disclose how the supplies secured through Project Airbridge were distributed. The administration is “bringing stuff back from China to the United States and then they’re delivering it to private companies in the United States, not to the states,” Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker told PBS NewsHour last month. “They’re letting all of us bid against each other for those goods that are owned by the private companies.” The Washington Post found that many of the areas hardest hit by COVID couldn’t confirm they’d received any supplies via Airbridge and that the supplies that were delivered were a fraction of what the administration had promised. In April, for instance, Vice President Mike Pence claimed the project was delivering 22 million masks a day. The Post found that the number of masks delivered was actually 2.2 million a day.

The inner workings of Project Airbridge and how much the companies may have profited from the arrangement are unclear. DOJ was tasked with overseeing the collaboration, but it did not respond to questions from Mother Jones. McKesson, Henry Schein, and Medline did not respond to requests for comment. Cardinal directed questions to DOJ and FEMA, which also did not respond to a request for comment.

After failing to get any information from FEMA or the White House, senators Warren and Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) wrote directly to the medical distributors to ask for specifics. “[T]he American people need an explanation for how these supplies are obtained, priced, and distributed through Project Air Bridge,” they wrote to the companies’ CEOs. “Unfortunately, neither the administration nor your company has explained critical details, such as the content of any existing contracts or financial agreements.”

Without a coordinated effort from the federal government, local governments and hospitals were left at the mercy of the distributors. “They have a state-sanctioned cartel,” says Sally Hubbard, director of enforcement strategy with the Open Markets Institute, a nonprofit that fights corporate monopolies. “The fact that the states have to bid and compete against each other to get a product from a monopolist is an atrocity.”

The histories of some of these companies do not instill confidence in their public service ethos. Cardinal Health serves nearly 90 percent of the country’s hospitals, selling medical products and prescription drugs. It also manufactures surgical apparel like gloves and gowns. Based in Dublin, Ohio, and Dublin, Ireland, a tax haven it uses to avoid millions in US taxes, the company paid $26.8 million in 2015 to settle a lawsuit with the Federal Trade Commission over allegations that it had illegally monopolized 25 local health care markets and forced hospitals and clinics to pay inflated prices. A few months ago, Cardinal paid nearly $9 million to settle bribery charges with the Securities and Exchange Commission related to its work in China. It earned $145 billion in revenue in 2019.

McKesson, which has more than $200 billion in annual revenues, distributes everything from opioids to vaccines to lab supplies. In 2012, the company agreed to pay $151 million in a multistate settlement over allegations that it had overcharged the Medicaid program by inflating prescription drug prices. It paid more than $190 million to the federal government in a related settlement that same year. In 2014, McKesson paid $18 million to settle claims that it allegedly filed false claims with the CDC related to its handling of childhood vaccine shipments.

Henry Schein was established in New York in 1932 as a small pharmacy. Today, after a long string of mergers and acquisitions, it has more than $13 billion in revenue and controls at least 40 percent of the dental supplies and equipment industry. In 2013, it paid $1.14 million to settle a case with the Department of Health and Human services over kickbacks to physicians. In 2019, the company agreed to pay out nearly $40 million to settle a class-action suit alleging that it had conspired with the nation’s other two largest dental suppliers to fix prices and to block the entry of companies charging lower prices into the market.

Medline Industries is an Illinois-based private company with nearly $12 billion in revenue that sells everything from Curad bandages to wheelchairs. In 2011, the company paid out more than $90 million to settle a whistleblower suit that alleged it paid kickbacks to hospitals and health care providers to get them to buy their products.

Both Cardinal and McKesson have also already paid out millions for failing to report suspicious orders of opioids from pharmacies, with billions more in settlements in the pipeline. Late last year, McKesson revealed in financial disclosures that it has received a grand jury subpoena from DOJ relating to a criminal investigation into the pharmaceutical industry’s role in the opioid epidemic.

Both McKesson and Cardinal are still in the middle of a massive probe into what state officials have called the largest price-fixing scheme in US history. More than forty state attorneys general have filed a civil antitrust suit against some of the nation’s biggest drug companies accusing them of colluding to raise prices on a host of common generic drugs by well over 1,000 percent. Distributors Cardinal and McKesson are not named as defendants in the lawsuits, but the lawsuit argues that they reaped a windfall from the scheme and failing to notify authorities about suspicious activity by the drug manufacturers. “It was the fox guarding the hen house,” Michael E. Cole, a Connecticut assistant attorney general leading the case, told the Washington Post last year. In October, a federal judge allowed a securities class action to proceed against McKesson alleging that it was a knowing participant in the generic drug price-fixing scheme.

These are the companies the Trump administration subsidized with free shipping flights from China—and relied on for advice on drug prices. The collaboration is “really the latest example of a huge risk of major profiteering from this crisis,” Hubbard says.

US antitrust enforcement has been lax for years, but the trend has accelerated since Trump took office. The criminal fines levied for antitrust violations by the DOJ have fallen 80 percent during the first two years of the Trump administration according to a recent study by the American Antitrust Institute.

Hubbard, of the Open Markets Institute, explains that the near-monopoly power in the medical supplies industry may be partly why the country is suffering from such massive shortages of the very equipment needed to combat the pandemic. Medline and Cardinal Health together control nearly 60 percent of the market for surgical apparel manufacturing, for instance. When there’s no competition, big corporations can raise prices as much as they want and have an incentive to keep supplies scarce to justify keeping prices high, she says.

Consumer advocates and small businesses also fear that the DOJ’s antitrust waivers given through Project Airbridge may allow medical distribution behemoths to completely crush what’s left of their competition during the pandemic, further weakening supply chains. For instance, Medline told ABC News in April that it was selling PPE at a loss and wasn’t charging customers extra for the expedited service it got through Project Airbridge. That might just be welcome corporate do-gooderism during a national crisis. But Diana Moss, president of the American Antitrust Institute, says that selling goods below cost is also known as “predatory pricing” in antitrust parlance. It’s a time-honored way of forcing smaller competitors out of the market because they can’t afford to match the artificially low prices. Moss doesn’t want to imply that this is Medline’s strategy, but in general, “That’s exactly the kind of conduct we worry about” with the antitrust immunity DOJ granted to the Project Airbridge companies, she says. “That would be a big red flag.”

Dennis Clock, owner of Clock Medical Supply, a family-owned medical supply business in Kansas, says Project Airbridge “absolutely” put his firm at a competitive disadvantage: “Companies like mine will find new market spaces and adapt. But there will be sectors of the marketplace that believe smaller companies don’t have the same access to critical PPE supplies as the large companies engaged in this project.”

It’s not just PPE or ventilators missing in action as a result of the medical supply market concentration. The coronavirus is particularly damaging to kidneys, causing a national shortage of dialysis equipment. Just two companies make more than 75 percent of the dialysis equipment, and they’re failing to keep up with demand. If and when there’s a COVID-19 vaccine, experts say the country will need 300 million to 600 million syringes to administer it. A single manufacturer, Becton, Dickinson and Company, controls 64 percent of the US syringe market. BD has been repeatedly sued over allegations of anticompetitive behavior. It’s currently embroiled in a class-action suit alleging that it bribed medical purchasing groups and conspired with four of the Project Airbridge distributors to jack up syringe prices. “These companies need tremendous oversight,” says Hubbard. “So no, these companies just can’t be trusted.”

In late April, Kushner told Fox News, “The federal government rose to the challenge and this is a great success story and I think that that’s really what needs to be told.” Less than two weeks later, even as health care facilities struggled to obtain protective equipment, the administration in effect declared victory and quietly disclosed that it was putting an end to Project Airbridge. According to notes obtained by NBC News, a FEMA official from the group organizing the pandemic response reassured workers concerned about PPE shortages in the future that Project Airbridge could still be revived “if urgent needs arise.”