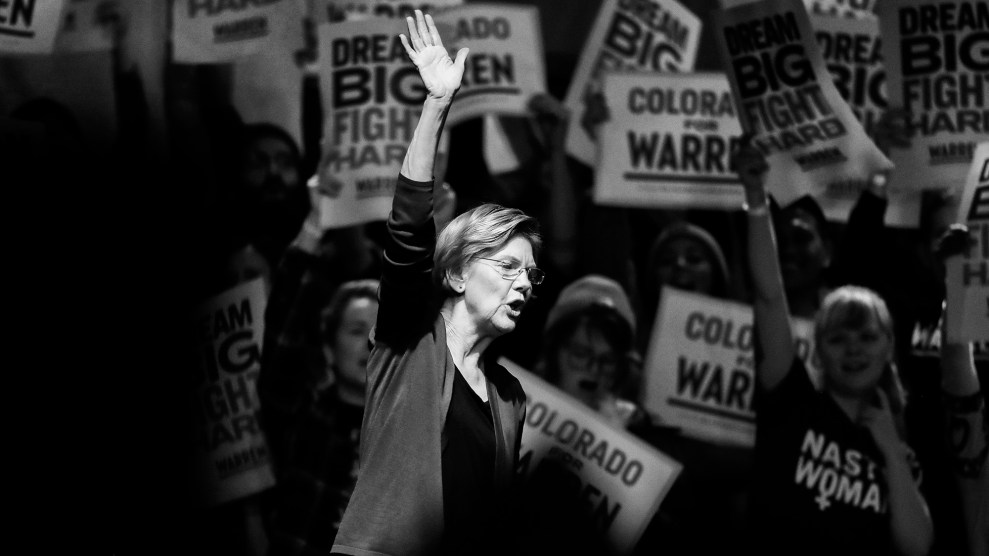

David Zalubowski/AP

On the morning of the South Carolina primary, reporters swarmed Elizabeth Warren in a tiny side room after a canvass kickoff in Columbia—her final event in the Palmetto State before departing for myriad Super Tuesday destinations. In her campaign trail uniform of black pants, black top, and jewel-toned cardigan—this one, aquamarine—the Massachusetts senator stood pressed against a wall that had been covered in her “Dream Big, Fight Hard” posters for the makeshift press conference.

She’d barely offered morning pleasantries before a television reporter barked a question her way: “When are you going to start winning?”

Warren was silent for a moment. “No one knew what a wealth tax was a year ago,” she finally said. “I’m loving this campaign. This a culmination of a lifetime of work.” Her ideas, she said, had a chance to live beyond “the academic side of things.”

She was still five days away from ending her campaign for the presidency, which she did today. But her words sure sounded like a candidate laying claim to her legacy. If that was, in fact, what Warren had intended with that answer, she did it well.

Elizabeth Warren ran to be our president. But the former Harvard law professor and bankruptcy expert leaves the race having accomplished something altogether different. She focused the national conversation on the question of just who government is supposed to work for and on the many ways those vested with its power have failed us. And she offered a detailed roadmap for solving these problems that will long outlive her candidacy.

Warren had entered the 2020 primary with a belly flop. A DNA test, taken to demonstrate once and for all her Native American ancestry, had royally backfired—enraging indigenous populations reminded of the ugly role that genetic science has played in their history and handing new ammunition to her right-wing detractors. But she kicked off her long road to recovery last February when she released the first of what would eventually be dozens of plans: A proposal to provide universal child care to all kids age five of younger, to be paid for by an “ultra-millionaire” tax on households with assets greater than $50 million.

If Warren were a typical candidate, that proposal might have been followed up a few months later with another. But as most of her competitors were still plotting campaign kickoffs, a plan to break up Big Tech appeared two weeks later. Another, promising to reverse decades of racist housing policies, was released just days after that. The near-weekly roll-out of new, meticulously crafted policy proposals throughout 2019 not only generated a steady stream of media coverage, but also enabled Warren to set the much of the agenda for the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.

With each new plan, Warren hammered home the message that America’s problems—sky-high hospital bills, unaffordable childcare costs, exploding student debt, meager savings accounts, Pentagon corruption—are not a forgone conclusion, but a choice made for us by a government that has put corporate profits and personal gain before the common good. And Warren, a gifted storyteller, could prove it, often sourcing anecdotes from her own life. Commuter college cost $50 a semester when Warren attended in the 1960s; the kindness of her Aunt Bee had been Warren’s childcare solution when she, a single mother, could afford no other.

When Warren’s own history wasn’t enough, she invoked the country’s past to prove her point. She focused particularly on the experiences of brown and black Americans, for whom racism has been baked into the centuries of state and federal policy. Warren gave five agenda-setting speeches during her campaign, using the history of place and struggle to weave together a narrative about the legacy of systemic inequality. Standing in New York City’s Washington Square Park, near the site of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, Warren talked about how corporate corruption has enabled the rich to tilt the rules in their favor. At Clark Atlanta University, a historically black college, in November, Warren honored the Washing Society—a union of Atlanta’s black washerwomen who launched a massive strike in the 1880s—and the struggles of domestic workers. She gave her last one in East Los Angeles, where she connected the legacy of farmworker organizers Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to how Latinx janitors had recently organized to protect their rights.

Warren’s detailed social justice agenda succeeded in drawing a devoted corps of activists to her side. But in the end, her campaign seemed to appeal mostly to white, college-educated voters—not the folks those plans had been designed to help the most, nor the ones who make up the core of the Democratic electorate. At times, her wonkish credentials obscured her compelling rags-to-riches origin story. “What too many voters see is Professor Warren from Harvard Law and not Betsy from Norman, Oklahoma,” Paul Begala, a Democratic strategist who worked on President Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign, told the New York Times.

Taken in sum, Warren’s plans offer a progressive vision. Between the lines of them is not just a what, but a how. Throughout the campaign, Warren repeatedly said that she would rather have a guarantee that someone else would enact her agenda than be president herself, and her exit from the race speaks to that desire. The question, of course, is whether the remaining contenders will take up Warren’s blueprint if they ascend to the Oval Office.

But even if that doesn’t happen, “Professor Warren” has changed the way at least some voters view the world. At a Warren rally outside Charleston last fall, I met a middle-aged white woman who told me she’d never heard the term “racial wealth gap” before Warren began using it during her stump speech—to talk about how her plans would level the playing field for people of color. If that’s the understanding of America that Warren leaves behind, that’s not such a bad thing.