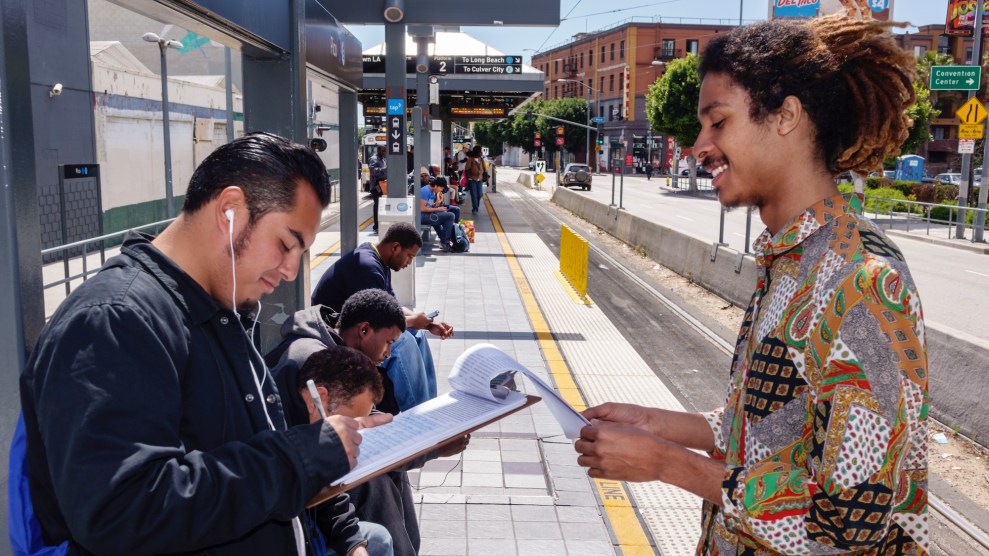

Members of the group “The Reckoning Crew" canvass for the Joe Biden campaign in Hopkins, South Carolina, on February 19, 2020.Gerald Herbert/AP

In 2020, Democrats were going to knock on a lot of doors.

Since the summer of 2019, the Democratic National Committee has trained more than 600 college students on the best methods for door-knocking, phone-banking, and party recruitment. In particular, the party focused on “relational organizing”—face-to-face conversations that typically leverage one’s own social network to develop long-term, community-building relationships. The initiative, called Organizing Corps, aimed to put 1,200 students—primarily from communities of color—on the ground in eight swing states well in advance of the general election. The idea was to turn those students into trusted messengers, a strategy based on research from the Analyst Institute that found this kind organizing can make a big difference in campaigns.

Then came coronavirus. Needless to say, there will be no face-to-face conversations for the foreseeable future. Instead, the DNC is exploring whether to move the rest of the trainings—and perhaps even the entire organizing effort—online.

Michigan, a pivotal swing state, already had 45 Organizing Corps graduates going door-to-door in the Detroit area last summer. Another 43 students completed the bootcamp at Michigan State University in East Lansing during the first week of March. Complementing those students’ efforts are 27 full-time organizers and a director of African American outreach who have been laying the groundwork for 2020. Now, much of that operation is resting on the shoulders of the Michigan Democratic Party’s single full-time digital organizer, who is charged with designing an online plan to salvage the program and, hopefully, to help the field staff move full-steam ahead during the pandemic.

In Wisconsin—the poster child of the crumbled Blue Wall—herculean efforts had been made to start early in a state Trump won by just 22,000 votes. Last summer, 30 Organizing Corps members knocked on 20,000 doors across every ward in Milwaukee. The state party, too, had hired organizers and has 250 volunteer neighborhood teams that knocked on half a million doors before the 2018 midterms. “You’ll see organizers and a presence in every part of the state,” David Bergstein, the DNC’s battleground states communications director, vowed in January.

Ben Wikler, the chair of Wisconsin Democrats, had already been building out a digital organizing strategy. But late last week, he decided that this digital initiative—originally planned as a complement to the in-person ground game—would instead replace it.

Since the 2016 election, the Democratic Party and its allies have been on an apology tour of sorts, one premised on the theory that Hillary Clinton didn’t lose because people wanted to vote for Donald Trump, but because voters who might have supported Democrats stayed home. And that, party leaders say, was the result of a failure of outreach to young people, women, and people of color. “We lost elections in the run-up [to 2016] because we stopped organizing,” DNC chair Tom Perez said in July 2018. “We stopped talking to people.”

So Democrats recommitted themselves to voter outreach, an effort that paid clear dividends in 2018. That organizing can continue, but there won’t be any doors knocked—not now, not soon, and, based on some predictions, not until sometime after November’s ballots have been cast (hopefully, by mail). And that’s left the party and its allies scrambling to figure out how it’s going to defeat Donald Trump in the fall.

“There’s been a transformative pivot to the very real possibility of running all-digital organizing programs, and as more states move to vote-by-mail elections, the reality is sinking in that we’ll have an election environment truly unlike any other,” says Nick Chedli Carter, a Harvard Kennedy School fellow who served as the national political outreach director for Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign.

To be clear, in-person organizing has long been just one slice of campaign field operations. House parties, town halls, and canvassing have their place, but so do texting, phone-banking, direct mail, and paid media blitzes. Face-to-face outreach is a time-intensive and expensive endeavor; even before coronavirus, its prominence had been shrinking in an increasingly digital world. But according to political scientists like Hahrie Han at Johns Hopkins University and Josh Kalla at Yale University, in-person conversations are a more effective means of campaigning than digital ones—partly because it’s becoming harder to connect with people over phone or email.

One concern for Wikler, the chair of the Wisconsin Democrats, is that those who are farthest from politics—the ones not in a voter file, for example—may remain politically impenetrable. “Democrats in Wisconsin have been knocking on the doors of people on nobody’s list and finding a mix of Trump supporters and undecided people,” Wikler explains. “A friendly face outside your door is an easier way to begin a conversation with someone who doesn’t feel like they’re connected to politics in any substantive way.”

Still, experts say that the new reality of social distancing isn’t necessarily a doomsday scenario. Kalla has found, for example, that phone conversations are the best way to reduce prejudice. High quality phone calls—in particular, live ones from volunteer phone banks—can increase voter turnout. What often makes face-to-face conversations more effective, Hahn says, isn’t the fact that they are done in person—it’s that these interactions have traditionally been seen as the foundation of authentic, human connections. If those connections can instead be forged digitally, door-knocking might not be necessary after all.

“Traditionally, people are best at constructing those relationships face-to-face, but nowadays people have been finding ways to create that same kind of connection virtually,” Hahn says. “To me, that is the challenge for organizers: How do organizers learn to draw power from relationships created online?”

Wikler says he’s thinking about how to best leverage trusted offline relationships in online organizing. “It’s difficult to build trust online, but trust that’s been built can be tapped online,” he tells me. And though strangers aren’t able to knock on doors right now, there are a lot of people whose daily schedules suddenly include a lot of free time—and who are desperate for human connection. “This is a recipe for a bigger virtual organizing effort than anyone’s been able to mount,” Wikler says. “The hardest part of relational organizing is getting people to reach out to their own contacts, but everyone’s in reach-out-to-your-loved-ones mode right now.”

Annie Weinberg, a veteran progressive strategist who advises on organizer trainings for groups like Our Revolution and Movement School—the organizing wing of the Justice Democrats—says that the earliest tests of this moment are, anecdotally, yielding results. “One of the volunteers came back crying from phone calls because she talked to a voter who had been isolated all weekend, and the phone call was the first interaction she’d had in days,” Weinberg says, describing a get-out-the-vote phone bank she facilitated before this week’s Arizona primary. “It can be healing to have someone there to listen to you in these times.”

Running for office during the coronavirus crisis is certainly an unprecedented challenge, but Weinberg says that there are some analogous situations candidates can draw from. Campaigns have had to plough ahead in the face of natural disasters, particularly around hurricane season, which often overlaps with the general election. She also pointed to the experience of candidates in places where face-to-face organizing is always difficult—for example, Gina Ortiz Jones, a Texas Democrat running for Congress in a massive, low-density district that encompasses two national parks. “Plenty of folks have figured this out,” Weinberg says.

The situation also shifts a new burden to the paid media side. Priorities USA, the Democratic super PAC that has committed $150 million to ads before the Democratic National Convention—with much more to come in the general—is reevaluating where its content should run, says Danielle Butterfield, the group’s paid media director. There aren’t any sporting events on TV right now, for example, but people might be streaming a lot of material from digital platforms. And she’ll be cognizant of the volume people are exposed to—now that they may be getting more screen time than ever. “We’ve always had a careful lens on how a paid media program layers on top of a field operation, and that’s not changing on our end,” Butterfield says. “But there are small tweaks we’re going to have to make.”

And what should be the message of those ads? Butterfield noted that Priorities had spent much of the last year talking about the inherent instability of the economy under Trump, something she says the pandemic has underscored. Melahat Rafiei, a DNC member and California-based strategist, says that the best way to engage folks might be to move away from politics for the time being. “Whether you’re mailing, emailing, or targeting through social media—instead of it being about a campaign, it should be about services to the community,” Rafiei says.

But even with the best online tactics, an unanswered question is who Democrats should be targeting. COVID-19 has thus far proven it can be a serious health threat for every age group, but experts say the elderly—the most reliable voting bloc—are the most at risk. “One of the most important ingredients in an election plan is knowing what kind of voters need what kind of contact,” Wikler says. “If voters who have voted every year since 1950 are now at the biggest risk for getting the virus, that changes things.”

“But the one counter to all this is that the urgency of voting is suddenly a life-or-death matter for millions of people, and that’s a very powerful countervailing force,” Wikler adds. “We don’t know how it works, but we’re in a new world now.”