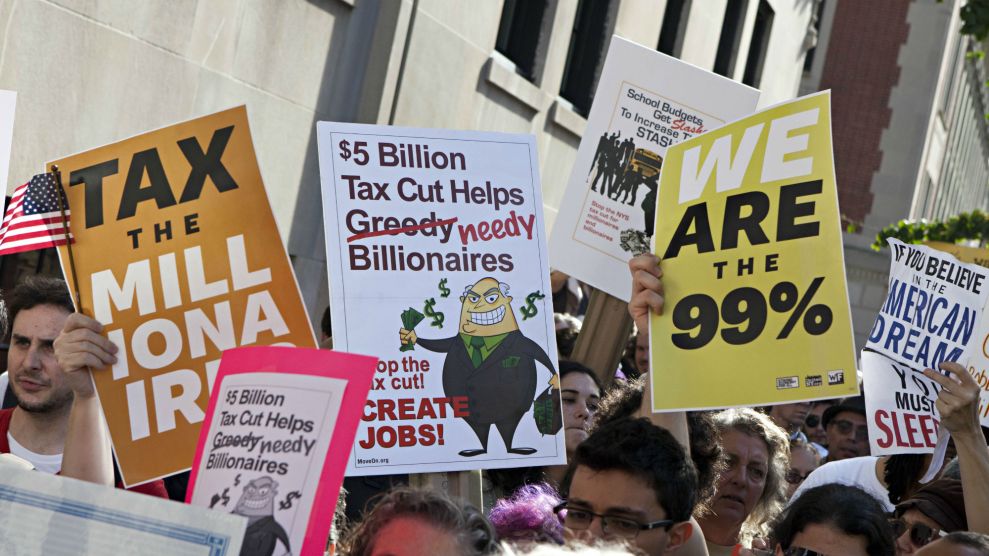

Thousands of teachers and their supporters march through downtown Raleigh, North Carolina during a one-day strike in May 2019.Ethan Hyman/ZUMA

Last May, for the second year in a row, thousands of North Carolina public school teachers marched to the state Capitol in red t-shirts to demand better funding for public schools and Medicaid. In part because of the strike, Governor Roy Cooper has refused to sign a budget that doesn’t include robust pay raises for educators.

North Carolina’s teachers weren’t the only ones who walked out on the job en masse last year. Data released this week from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that 2019 had a higher number of “major work stoppages,” meaning strikes and lockouts, involving 1,000 or more workers than any year since 2001. The Economic Policy Institute notes that 2019 also saw the most strikes involving 20,000 or more workers than any year since 1993, when BLS first started keeping track.

The General Motors strike in September and October was the largest strike of the year in terms of work days lost; the 29-day strike, involving 46,000 workers, resulted in a cumulative loss of more than a million days of labor and a $600 million loss for GM.

But the rise in strikes has overwhelmingly been dominated by the education sector. More than half of all workers on strike last year were teachers, BLS data shows. The three largest strikes of the decade were held by teachers in North Carolina (twice, in 2018 and 2019) and in Arizona. While some teachers went on strike for better pay, many focused on legislative cuts to education and expansion of charter schools.

In a 2018 Mother Jones story, Eddie Rios and Annie Ma analyzed data to show the decline of public school funding since the economic crash. “Education spending fell sharply following the recession,” they wrote. “In 2016, 25 states provided less funding per pupil for public schools than they did before the 2008 recession.”

As I wrote in December, the 2010s saw a surge of labor strike activity led largely by teachers unions:

The Chicago strike, which won teachers a 16 percent raise over four years and reduced emphasis on test scores in their evaluations, showed teachers around the country what was possible. By the end of the decade, the tactics used in Chicago had surged nationwide. The West Virginia teachers’ strike of February-March 2018 was soon followed by statewide strikes in Arizona, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Colorado and North Carolina—and by big wins. West Virginia teachers won a five percent pay raise and a commission to deal with insurance costs. In 2019, Los Angeles teachers won more counselors, nurses and librarians for their students. In Kentucky, Gov. Matt Bevin’s battles with the teachers’ union may have cost him reelection.

The end-of-decade rise in strikes comes even as the unemployment rate remains below 4 percent. In a report released yesterday, researchers at the Economic Policy Institute suggest that this means workers feel confident that if they lose their job for striking, they can find another. It also suggests workers are unsatisfied with their pay. “Working people are not seeing the robust wage growth that one might expect with such a low unemployment rate,” the researchers stated, “and inequality continues to grow.”