slobo/iStock/Getty

This piece was originally published in The Guardian and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

Deadly urban heatwaves disproportionately affect underserved neighborhoods because of the legacy of racist housing policies which have denied African Americans home ownership and basic public services, a landmark new study has found.

Extreme heat kills hundreds of people in the US every year—more than any other hazardous weather event, including hurricanes, tornadoes and flooding, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Heatwaves have been occurring more frequently since the mid-20th century, and are expected to become more common, more severe and longer-lasting due to the climate crisis.

However, exposure to extreme heat is unequal: temperatures in different neighborhoods within the same city can vary by 20F. It is mostly lower-income households and communities of color who live in these urban “heat islands” which have historically had fewer green spaces and tree canopy, and more concrete and pavements and thus are less equipped to cope with the mounting effects of global heating.

This new study reveals how current temperature disparities echo the legacy of past racially motivated town planning. Urban neighborhoods denied municipal services and support for home ownership during the mid-20th century are now the hottest areas in 94% of the 108 cities analysed by researchers at Portland State University and the Science Museum of Virginia.

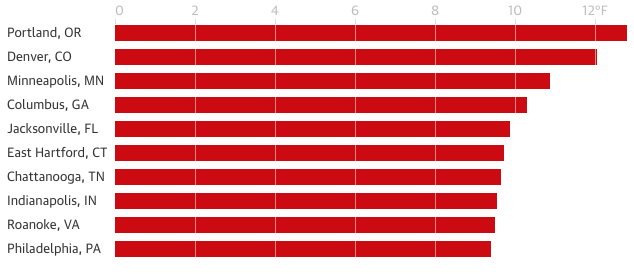

Heat differences between redline and non-redlined neighborhoods (Fahrenheit).

Researchers from the Science Museum of Virginia, Portland State University and Virginia Commonwealth University / Guardian

“This systematic pattern suggests a woefully negligent planning system that hyper-privileges richer and whiter communities,” said Vivek Shandas, professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University who authors the paper.

The study, published today in the journal Climate, is the first to examine the link between historical housing policies to disproportionate exposure to current deadly heatwaves.

“As climate change brings hotter, more frequent and longer heatwaves, the same historically underserved neighborhoods – often where lower-income households and communities of color still live – will face the greatest impact,” Shandas added.

Globally, temperatures have been rising since the beginning of the 20th century, with 18 of the 19 warmest years on record occurring since 2001.

Each year, more than 600 Americans die and 65,000 or so seek emergency medical care for excessive heat exposure. As heatwaves become increasingly frequent and severe, scientists expect to see an increase in deaths and illnesses, particularly among vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, economically disadvantaged communities, and those with pre-existing conditions like heart disease, asthma and diabetes

This new study examined the link between historic “redlining” and current heat islands.

Beginning in the 1930s, some, mostly African American neighborhoods – designated with red lines – were categorized as too risky for investment, and denied home loans and insurance.

As a result, the housing stock fell into disrepair, and residents were unable to create wealth through homeownership or move into “better” suburban neighborhoods, which intensified segregation and wealth inequalities. Redlined neighborhoods also had the lowest public and private investment.

Researchers used satellite images to analyse the relationship between summertime surface temperatures and “redlining” in 108 cities across the country.

Nationally, the study found formerly “redlined” neighborhoods are 5F warmer, on average, than non-redlined neighborhoods.

However, the difference is much starker in some cities. For instance in Portland, Oregon, and Denver, Colorado, researchers found a 12 to 13F difference between formerly redlined and non-redlined neighborhoods, compared with 1-2 F in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania and Flint, Michigan.

“The patterns of the lowest temperatures in specific neighborhoods do not occur because of circumstance or coincidence. They are a result of decades of intentional investment in parks, green spaces, trees, transportation and housing policies that provided ‘cooling services’, which also coincide with being wealthier and whiter across the country … neighborhoods are not made equal,” said Shandas. “We are now seeing how those policies are literally killing those most vulnerable to acute heat.”

“This study is a textbook case of how structural racism in housing compounds environmental, climate and health risks,” Dr Robert Bullard, distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, told the Guardian. “Zip code is still a potent predictor of health and well-being… environmental vulnerability maps closely with racial injustice.”

Redlining was banned in the 1968 Fair Housing Act, but those neighborhoods are still predominantly home to lower-income communities and communities of color who are disproportionately exposed to a variety of environmental hazards such as lead, poor water and air quality, over development and limited shade.

Numerous studies have exposed the legacy of these historic policies in racial disparities in healthcare, access to healthy food, incarceration and public resources allotted for schools, transport and and other public infrastructure.

Now, these results illustrate a need for better urban planning and climate mitigation policies.

“Our study is just the first step in identifying a roadmap toward equitable climate resilience by addressing these systemic patterns in our cities,” said coauthor Jeremy Hoffman of the Science Museum of Virginia.

Shandas added: “By recognizing and centering the historical blunders of the planning profession over the past century, we stand a better chance for reducing the public health and infrastructure impacts from a warming planet.”