Curtis Compton/Atlanta Journal-Constitution/AP

Kamala Harris is out.

The junior senator from California suspended her bid for the Democratic nomination for president Tuesday afternoon. The announcement capped off a historic campaign that started with a bang and quickly devolved into a sputtering operation torn between two coasts and warring staffers, according to damning reports from Politico and the New York Times. Harris entered the race as one of the favorites but ended it polling in the low single digits—far behind Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigeig, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana.

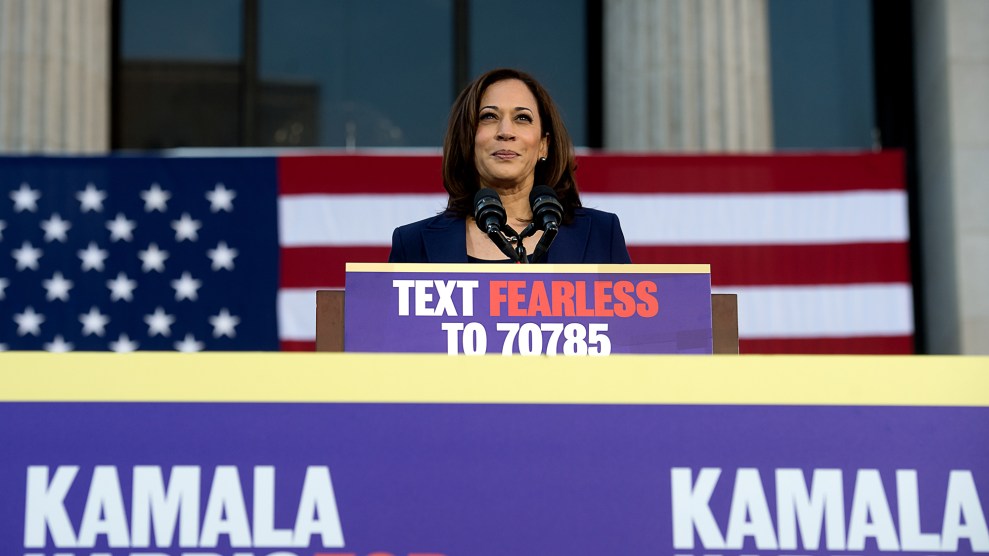

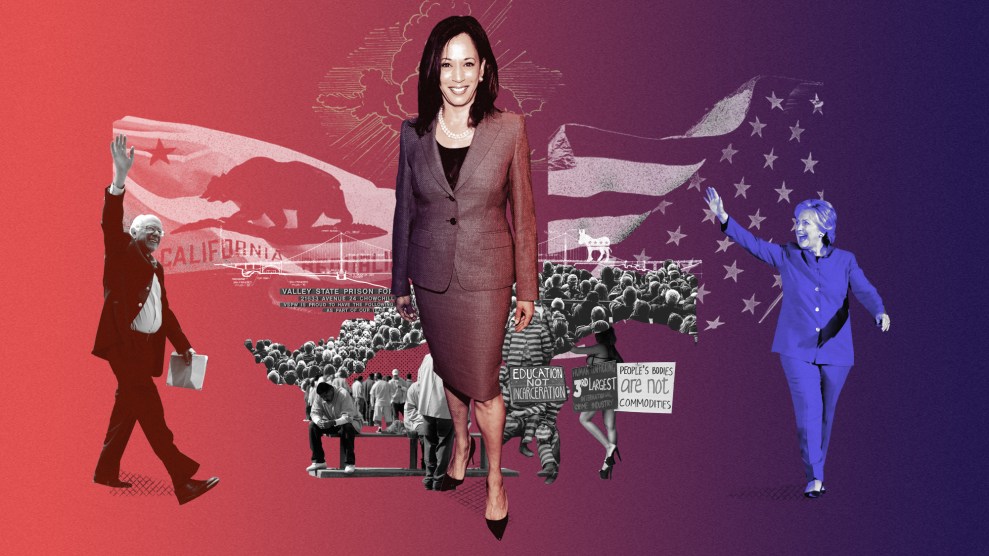

Harris is used to making history. As a biracial black woman of Jamaican and Indian descent, she ticked off a list of firsts as she climbed the ranks of national politics. She was the first woman, at the age of 38, to lead San Francisco’s district attorney’s office. She was the first black woman and first Asian American woman to serve as California attorney general and US senator from the state. She centered her campaign on the symbolism of pioneering black women politicians who came before her, like Shirley Chisholm, whose historic 1972 run for president inspired everything from Harris’ first stump speeches to her team’s retro yellow, purple, and burnt orange design scheme.

But in the end, it was Harris’ own history that worked against her. As district attorney, she pioneered an innovative program that kept nonviolent first-time offenders out of jail. But she also boasted a tough-on-crime approach, including truancy programs that sent a handful of parents to jail. Harris, still in her first term in the Senate, ultimately could not reconcile the nearly two decades she spent in law enforcement with a rapidly changing political landscape on criminal justice issues that’s driven by the progressive base’s desire for systemic change.

This narrative was baked in early, even before Harris launched her campaign in front of 20,000 people in her hometown of Oakland. Days before her official entry into the race, Lara Bazelon, a law professor at the University of San Francisco and a former public defender, published a scathing opinion piece in the New York Times titled “Kamala Harris Was Not a ‘Progressive Prosecutor,'” pushing back hard against Harris’ claims in her memoir that her prosecutorial approach was in line with modern-day reformers like Larry Krasner in Philadelphia and Kim Foxx in Chicago. “If Kamala Harris wants people who care about dismantling mass incarceration and correcting miscarriages of justice to vote for her, she needs to radically break with her past,” Bazelon wrote.

And then there were the searing stories of the human toll of Harris’ career in California. Jamal Trulove, a San Francisco man convicted of murder by her DA’s office, later had his conviction overturned and won a $13 million settlement. Cheree Peoples was arrested in 2013 during Harris’ crackdown on truancy as attorney general—even though, as the Huffington Post reported, Peoples’ chronically truant daughter was in fact battling sickle cell anemia. Several news outlets later reported that Harris’ campaign battled internally over how to talk about her record as a prosecutor—she did issue a handful of apologies—but never settled on anything beyond telling voters that she had the prosecutorial chops to take on Donald Trump.

In the last months of her campaign, as rivals like Warren and Sanders enlivened the Democratic base with ambitious and unapologetically ideological agendas to remake health care and cancel student debt, Harris seemed to move tepidly. In one interview with the New York Times, she boasted about not being ideologically driven and said that she was instead a pragmatist focused on solutions.

Harris’ standout campaign moment came during a debate in June, when she challenged Biden’s record on school desegregation by pointing to her own childhood, when she was bused to a nearby majority-white school in Berkeley.

That moment sowed the seeds for what could have been a true breakout moment—there were t-shirts and memes—but it ultimately failed to do much in the long run. Turns out, words and memes weren’t enough to convince Democratic voters that Harris was the right choice to run against Trump.