Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, D-San Diego, speaks at a rally about her measure to limit how companies labeling workers as independent contractors.Rich Pedroncelli/AP

On Monday, the sports blog SB Nation, owned by Vox Media, announced it was reorganizing its model in California and would be laying off most of its staff of two hundred freelance writers and editors. Those laid off were told they could apply to a few dozen new employee positions or, according to a leaked email sent to SF Gate, work as “Community Insiders”—blogging for free. The reason? A new labor law.

In a blog post titled “Thank You California,” the company explained that the shift “is part of a business and staffing strategy that we have been exploring over the past two years,” adding that it became “necessary in light of California’s new independent contractor law.” What that justification doesn’t mention is that there are multiple lawsuits pending against Vox Media that allege the company was misclassifying workers to avoid overtime and minimum wage requirements. (Vox Media did not respond to a request for comment.)

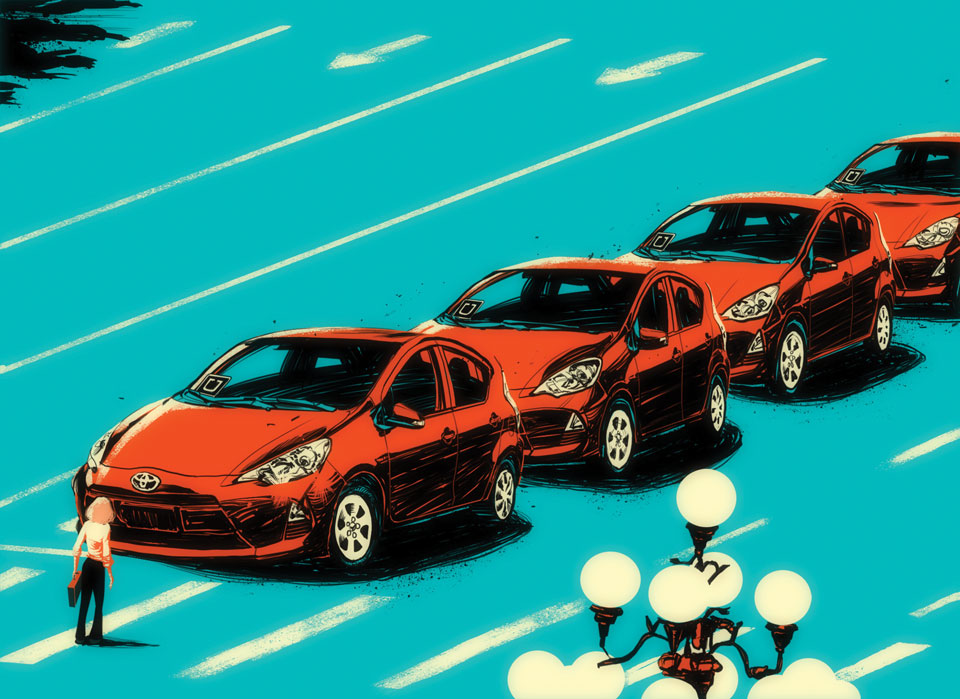

Instead, SB Nation management is blaming a new California law, Assembly Bill 5, which will take effect in the new year. The law clarifies a California Supreme Court decision, called Dynamex, from 2018 that imposed an “ABC” test to determine who is an independent contractor. Critics have been saying that AB5 changes everything for freelancers. It does not. What it does is make it harder for employers to get around basic worker protections (think benefits, pay) by deeming everyone a contractor—although with many exemptions; freelance journalists, for example, only require employment status if they write 35 articles or more a year for a publication. Similar laws exist across the country.

But AB5 has already become an invaluable scapegoat for companies looking to make cuts. With it, Vox’s actions are not only forgivable but sane—it made the story an inevitable outcome of regulation. Like when you cut jobs after a minimum wage hike.

“I don’t blame them at all,” wrote Rebecca Lawson, who runs the SB Nation Mavericks vertical site remotely from California. But she did blame “California’s terrible AB5.” (Lawson said the blog was her comment on the issue when contacted by Mother Jones.) Memes appeared on Monday of Vox.com‘s reporting on AB5’s aid to gig workers juxtaposed beside the layoff numbers for Vox Media (the parent company of both SB Nation and Vox). On Tuesday, the American Society of Journalists and Authors, repped by the libertarian Pacific Legal Foundation, announced a suit challenging the law over freedom of speech—joined by photojournalists. A drumbeat continued that has been banging since the law was being considered earlier this year: AB5 will kill freelance journalism in California.

But all of this misses the point. Even before AB5, the model SB Nation used was likely illegal. And it was being sued because of it. Currently, across all of its teams, SB Nation has non-employees—often for a low-wage—contract as site managers and churn out content. Writers created tight-knit and insular communities: Golden State of Mind, Niners Nation, Turf Show Times. And that was fun but also, um, an “army of exploited workers,” as Laura Wagner wrote for Deadspin. The lawsuits document the work of “Site Managers” and non-employees, like Michigan-based Cheryl C. Bradley of Mile High Hockey, who wrote five articles a week, managed other writers, combed through the comment section, and took directives from Vox management. Bradley even ran the social media accounts. “Bradley regularly worked thirty to forty hours per week,” according to the suit, “and was compensated at a rate of $125 per month.” That’s about $6 a day.

You don’t need AB5 for that to be illegal. The two class-action lawsuits making their way through federal courts both rely on regulations before AB5. One, from Bradley, was certified in March in federal court (months before AB5 passed in California) and alleges Vox Media was violating federal fair labor standards. The other started in California in 2018 and uses the state’s owns rules before AB5 to challenge the legality of the independent contractor status of SB Nation writers. AB5 just makes it hard to get out of punishment for this.

“The ABC test—which went [partly] into effect after Dynamex in April 2018—would make it much harder for them to defend their dubious position that the reporters were independent contractors,” Veena Dubal, a professor at the University of California Hastings, said in an email. “The [previous] test had slightly more wiggle room, but the reporters were still very likely misclassified under that test.”

And in this sense, SB Nation is actually a startlingly good example of why the law is important.

“I understand that fear of loss of income and I empathize with that. But I also understand that if we don’t start standing up in making and requiring companies to change, this will continue to spiral,” says state Rep. Lorena Gonzalez, a Democrat from San Deigo and one of the authors of AB5. That’s why, when journalist advocacy groups asked for a total freelance exemption to the law, she wouldn’t add it. “Seriously: [SB Nation’s] model was one by which they were already seeking out free writers to do work. And we’re going to say yes?”

Those 200 freelance “jobs” SB Nation /Vox announced ending yesterday & replacing w/staff jobs are better described here. I’m sure some legit freelancers lost substantial income, and I empathize with that especially this time of year. But Vox is a vulture. https://t.co/qsAktJILBx

— Lorena (@LorenaSGonzalez) December 17, 2019

For some SB Nation writers, the new law makes sense. “I do not think it is a secret that Vox Media’s employment model has long been unsustainable,” Lucas Hann, the editor of Clips Nation, an SB Nation blog, wrote in a brief post after the announcement.

Hann—who worked at SB Nation for eight years—told me he thinks the responsible thing would’ve been to hire the people they’d been likely misclassifying all that time.

“To me the law isn’t really what matters here,” Hann said. “What matters is that corporations like Vox Media are exploiting people for huge profits. And regardless of what happens with the law, they’re going to find new ways to continue doing that. They’re using the law as a shield to lay people off.”

There is a case to be that freelancers are being harmed by being classified as employees. Some freelancers want to forgo certain benefits—healthcare, overtime protections—tied to employment in favor of a flexible schedule or job freedom. The prescriptive, and speed-limit like 35 “submissions” per outlet to define employee versus an independent contractor is imperfect. But the mistake is the belief that AB5 suddenly changed all of this. To change this model, you’d have to undo years of the law tying employment status to worker’s rights.

For now, the fallout from fixing years of wrong seems to be only providing an excuse for companies to keep up doing what they’ve always done: fire people and fight regulation.