In early 1973, as Joe Biden was settling into his new job in Washington, DC, Ralph Nader published a deconstruction of what made the freshman Democratic senator’s state of Delaware, the most anodyne of states, so exceptional. The answer, The Company State explained, had to do with the unique relationship between government and commerce: Delaware was less a democracy than a fiefdom, contorting its laws to meet the demands of its corporate lords.

Preeminent among them was the chemical giant DuPont. Nader took readers to Rodney Square, in the heart of Wilmington. There was the ritzy Hotel du Pont, housed in a building owned by DuPont, next to a theater built by DuPont, connected to a bank controlled by the du Pont family, surrounded by law offices and brokerages—all affiliated in some way with what was known simply as “The Company.” The du Ponts owned the state’s two largest newspapers and employed a tenth of the state legislature. The governor was a former executive. The state’s member of Congress for most of the 1970s was Pierre Samuel du Pont IV.

“General Motors could buy Delaware,” Nader quipped, “if DuPont were willing to sell it.”

Over the next two decades, as Biden rose through the ranks of the Democratic Party, the state’s center of gravity began to shift from the world of chemicals to the big business of other people’s business—banking, accounting, law, and telemarketing. But if the industry had changed, the ethos remained: Delaware was the Company State. It owed its prosperity to its willingness to give corporations what they wanted.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Though he’s now a millionaire thanks to book sales and speaking fees, Biden has long positioned himself as the champion of the middle class, a scrappy kid from Scranton who’s fought the good fight for decades. His adopted home state is part of that identity too—an unglamorous enclave of scrapple and toll roads, the Acela Corridor’s own Flyover Country. But as he pursues his third and likely final quest for the Democratic presidential nomination, his record haunts him, because the interests of Delaware are often at extreme odds with everyone else’s.

Biden did not create this system, but he used his influence to strengthen and protect it. He cast key votes that deregulated the banking industry, made it harder for individuals to escape their credit card debts and student loans, and protected his state’s status as a corporate bankruptcy hub.

Biden’s career in the Senate placed him on the wrong side of some of the biggest financial fights of his generation and brought him into conflict with some of the same rivals he faces today. If you want to understand how Biden became Biden, you have to understand how Delaware became Delaware.

Delaware is a tiny state, and because it is tiny, it has had to get creative to survive. Small countries sell shipping rights, citizenship, and secrecy. Delaware offers an American variation of the same—a legal and administrative sanctuary that allows businesses to do things there that they could not do elsewhere.

The foundation for the state’s economy began with its 1776 constitution, which created a special venue for the handling of business disputes, called the chancery court. But Delaware’s role as America’s corporate epicenter traces back to 1899, when—with the backing of the du Ponts—legislators passed the General Corporation Law, allowing anyone in the United States who wanted to form a company in Delaware to do so. The number of corporations based in the state grew quickly, and when New Jersey—the OG of lax incorporation laws—decided to crack down on trusts, Delaware welcomed the exiles.

The incorporation law made it easy to set up shop in Delaware, and the chancery court made it convenient to stay. Companies knew they’d get a reliable pro-business forum for their disputes. Today, there are nearly twice as many Delaware-incorporated companies as there are Delaware voters, and incorporation fees constitute the second-largest share of the state’s annual revenue.

But Delaware’s windfall comes at the expense of other states. Corporations can place their profits in Delaware-based holding companies to avoid paying taxes in the places where they actually operate. Delaware LLCs can also be incorporated anonymously via third-party agents, stifling transparency. “Setting up a company in Delaware,” the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy says, “requires less information than signing up for a library card.”

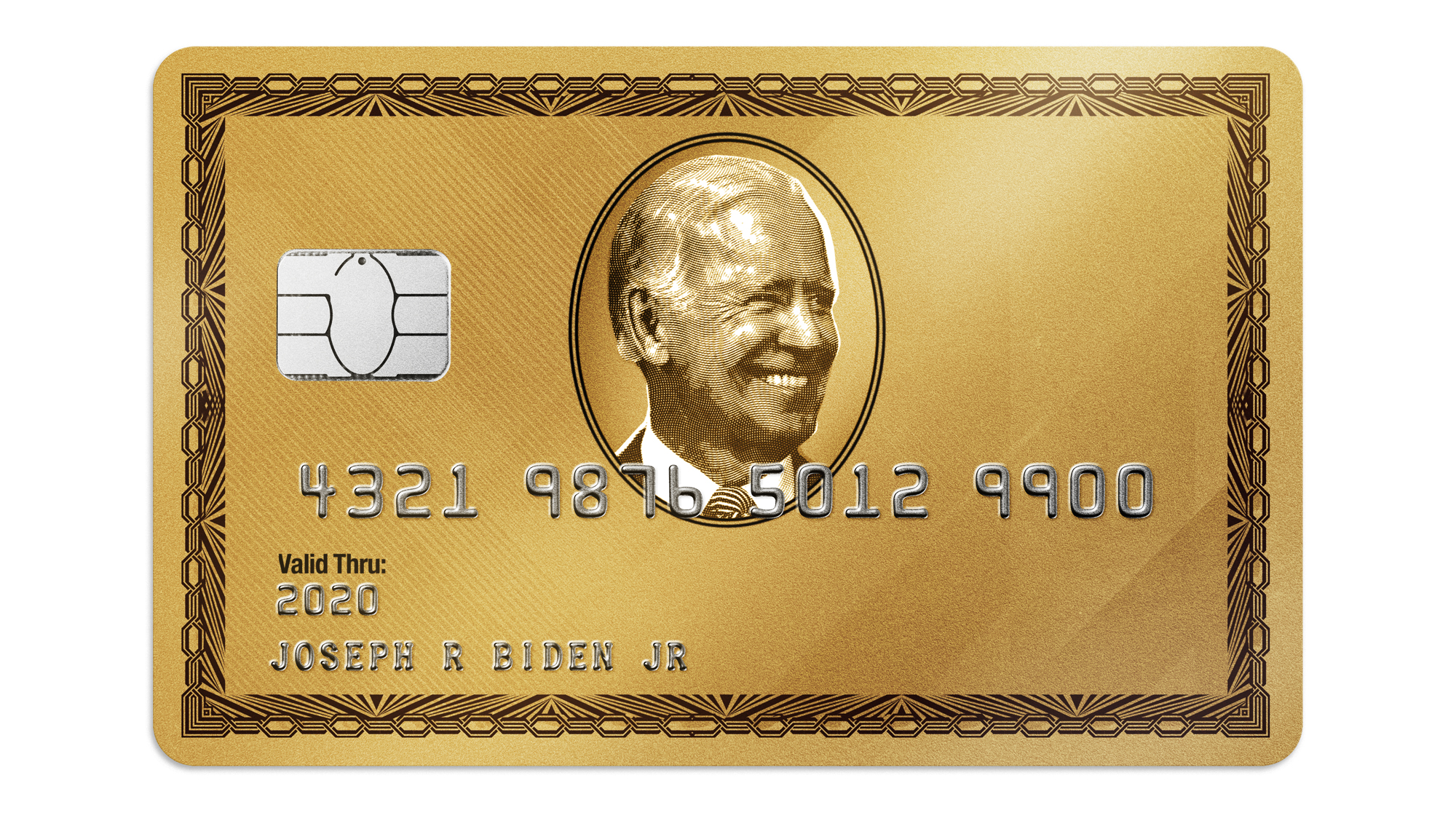

When the economy sagged in the late 1970s, the cash-strapped state began looking for ways to supplement its income. In 1981, it passed a new law, written by banking lobbyists and backed by DuPont, with the hopes of becoming, in the words of the governor who signed it (a du Pont, naturally), “the Luxembourg of the United States.” While other states were setting caps on usury rates, Delaware told banks they could charge whatever they wanted in annual interest and late fees; the banks could also foreclose on debtors’ homes if they fell behind on payments. The state even cut corporate taxes.

The result was a corporate gold rush. A dozen companies, including JP Morgan and Chase Manhattan (now JP Morgan Chase), opened offices in Delaware in the first year alone. By the late ’90s, four of the five largest credit card firms in the country had set up in Wilmington, and the industry employed at least 35,000 people. The Company State had pulled off a lucrative turnaround.

The state’s decision to turn itself into New Luxembourg ushered in an era of economic prosperity that coincided with a political era of good feelings. The rebooted Delaware was emblematic of the kind of gauzy comity that Biden has sometimes gotten in trouble for waxing nostalgic about. Elected officials from both parties prided themselves on what they called “the Delaware Way”—a willingness to put aside partisanship for the good of the state, which invariably meant aiding its business climate. Revenue from corporate taxes and LLCs kept government coffers full, and the state’s low income tax rates kept voters happy.

For decades, much of the front-line work of championing the state’s industry in Washington was handled by the state’s senior senator, Republican William Roth, a Senate Finance Committee member so absorbed in such matters that there’s a tax-free retirement account named for him. But Biden did his part too.

A letter I found in Roth’s Senate papers at the Delaware Historical Society offered a glimpse of how closely banks worked with the state’s delegation. In 1998, an executive at First USA, a credit card company based in Wilmington, wrote to Roth, asking him to intervene on a proposed rule that would shorten the window in which credit card companies could collect debts from debtors. A few days later, Roth, Biden, and a Delaware representative did just that. “Reducing the collections period for credit card debt by one-sixth would have a direct effect on Delaware banks,” the lawmakers wrote to federal regulators. “Many Delaware bankers are concerned that such a change would unfairly result in substantial losses to their institutions.”

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, as Biden settled into a comfortable incumbency, banks sought to make the rest of the country work more like their mid-Atlantic refuge—to embrace the least possible amount of regulation so they could grow as big as they wanted. Delaware, for instance, had a loophole allowing banks to sell insurance. Now the banks wanted to do that everywhere. Delaware’s laws made it easy for credit card companies to do business in any states they pleased. Financial firms wanted regular deposit banks to have that ability too.

Biden supported a baby-step deregulatory effort in the early 1980s, and then, in 1994, he backed a very big one: the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act, which eliminated the remaining barriers to where banks could operate. The law passed with overwhelming bipartisan support and was fairly innocuous in some respects, codifying changes that were already happening at the state level. But it opened the floodgates to an era of corporate consolidation. Delaware’s financial institutions got another big boost in 1999, when Biden voted for the Financial Services Modernization Act, which repealed the Depression-era Glass-Steagall law barring banks from owning securities and insurance businesses. By 2016, there were almost 5,000 fewer banks in the United States than there were two decades earlier, and the 10 largest firms controlled half of all banking assets.

The metastasis of America’s financial conglomerates proved catastrophic when those increasingly huge banks began to package subprime mortgages as securities a few years later. (Biden, for his part, opposed the 2000 law that deregulated derivatives.) During the 2008 campaign, even after Biden had been added to the presidential ticket, Barack Obama cited Glass-Steagall’s repeal as a stepping stone to the financial collapse. Recently, Biden has been apologetic, if somewhat cryptic, about that vote. “I’ll be blunt with you: The only vote I can think of that I’ve ever cast in my years in the Senate that I regret—and I did it out of loyalty, and I wasn’t aware that it was gonna be as bad as it was—was Glass-Steagall,” he told the New Yorker in 2014.

Even when Biden was nominally bucking his state’s business interests, he did it gently. In 1991, to the horror of Delaware companies, he supported amending a banking regulation bill to impose a nationwide cap on credit card interest rates. He explained that he had voted for the amendment only because he considered it a poison pill that would force the Senate to pass much narrower legislation. It worked.

But the most controversial item on the banks’ agenda, and the one that would require the most legwork from Biden, was bankruptcy reform.

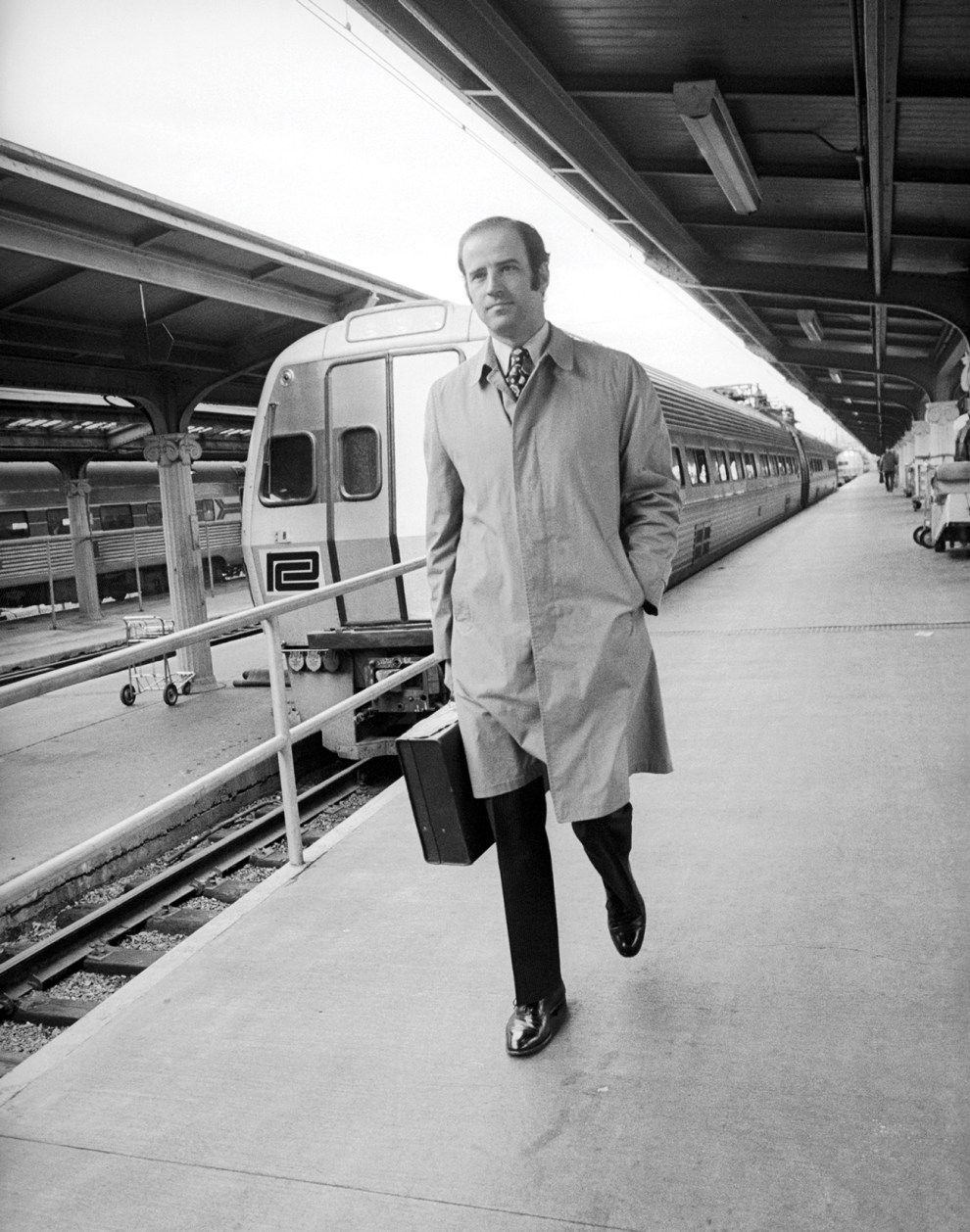

Senator Joseph R. Biden, D-Del., is seen here at Union Station where most days, after the Senate adjourns, he caught the Metroliner to Wilmington for home.

Bettmann/Getty

Late in Biden’s 1996 reelection campaign, a consultant working for his Republican opponent pushed a troubling story: The senator had sold his home to an executive from the credit card company MBNA for double its appraised value. MBNA called the story “viciously false,” and Biden pushed back hard enough that his opponent fired the consultant. True, he had sold his house to an MBNA executive—but at its appraised value. Not long after that, though, the company hired Biden’s youngest son, Hunter, and the criticism stuck: Biden became, to his detractors, “the senator from MBNA.” (Hunter’s corporate affiliations have once again become an issue for Biden. His son’s role on the board of a Ukrainian energy company while Biden oversaw the Obama administration’s Ukraine policy has fueled corruption accusations and conspiracy-mongering by Republican critics; Donald Trump’s effort to force Ukraine to investigate the Bidens is now at the center of the impeachment inquiry.)

MBNA, the largest independent credit card company headquartered in Delaware, hardly drew notice at first. In 1982, five employees from a company called Maryland Bank set up shop in an old supermarket a few miles from the state line. They hit upon the idea of pitching credit cards to targeted groups—like sports fans or college students—and did a quarter of a billion dollars of business in just over a year. By 1997, MBNA was mailing 30 million credit card solicitations a month and making 6 million over the phone. Getting people into debt was how the company profited, and it was self-perpetuating. If a debtor missed a car payment to pay a credit card on time, MBNA would raise the person’s interest rate anyway, a practice known as universal default—thereby increasing the likelihood the person would miss future payments.

Because MBNA did all of its work in-house—even telemarketing and customer service—its Wilmington-based payroll dwarfed rival firms’. MBNA employed about a third of the state’s finance workers. The company stockpiled vintage cars (a Duesenberg was parked in its lobby) and began buying up old DuPont properties—office buildings and golf courses—and slapping its logo on new and renovated buildings overlooking Rodney Square. When, in the early 2000s, the chancery court relocated to a bigger building, MBNA bought the old one.

MBNA brought the same largesse to politics. It shelled out nearly $1 million in donations to federal candidates in 1994, the same year an array of pro-business Republicans took control of Congress. These donations came from individual employees, not the corporate treasury, but the Wilmington News Journal obtained an internal memo from the bank’s chief counsel directing 150 MBNA execs on whom they should contribute to, even asking them to send photocopies of their checks.

Most of the money flowed to Republicans—MBNA employees were George W. Bush’s largest contributor during his 2000 presidential campaign—but Biden was an exception. He brought in more than $200,000 from MBNA employees over the course of his career. And he developed a relationship with the company’s CEO, Charles Cawley. When Biden held a Wilmington fundraiser for his 1996 campaign, Cawley was there. When Cawley received an award for his charitable giving, Biden and Bush appeared onstage with him. A couple years later, Cawley co-chaired an award ceremony for Biden. On the company’s dime, Biden and his wife, Jill, flew to Maine, where the senator spoke at MBNA’S 1997 corporate retreat.

MBNA lobbied for the repeal of Glass-Steagall, according to the News Journal, and because MBNA’S business model was based on delinquent customers, it lobbied to block reforms meant to help cash-strapped consumers, such as crediting bill payments to the day they are mailed rather than the day they are received. But what it was really after was bankruptcy reform.

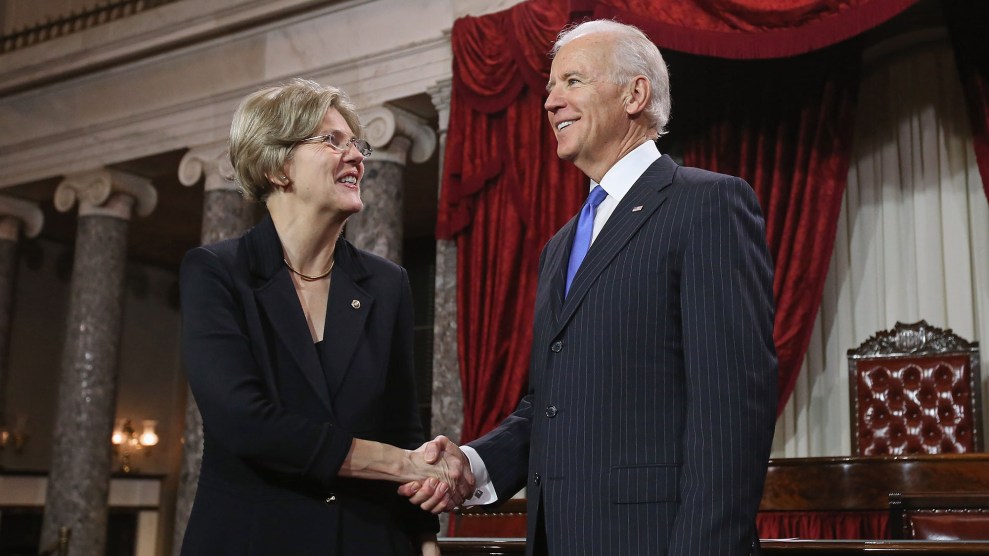

Between 1980 and 1997, the number of Americans filing for personal bankruptcy jumped more than 300 percent, affecting 1.3 million households annually. A growing number of researchers, led by a Harvard Law School professor named Elizabeth Warren, believed the fault lay with the accumulating credit card fees, hospital bills, student loans, and mortgages that were placing the squeeze on middle-class families. Their research found that, for debtors, personal bankruptcy was not an escape hatch; it was a lifeline.

A congressional effort to curb bankruptcies might have started with looking at how people were getting into debt. Instead, Congress tackled the problem from the perspective of the creditors, who argued that stricter rules were necessary to forestall abuses of the system and prevent billions of dollars in losses from trickling down to consumers. In 1997, a group of House lawmakers began crafting a bill that would make it harder for individuals to file for bankruptcy by subjecting filers to a means test and giving creditors more opportunities to collect. The credit card companies loved it. After all, they wrote large chunks of the legislation.

Biden voted to make the bill more moderate, and it died. Then he supported an altered version introduced in the next Congress. Bankruptcy reform would go through the judiciary committee that Biden sat on and had once chaired, and, in the words of one lobbyist, he was the “linchpin” of the effort to pass it.

Credit card companies wanted to limit the options of people filing for personal bankruptcy, but that was only one part of the equation. Delaware also had a lot riding on helping corporations file for bankruptcy. For a variety of reasons, including its high concentration of white-collar lawyers and the pro-business reputation of its courts, the state was the venue for a large percentage of the nation’s Chapter 11 cases. It had even come up with a special fast-tracked bankruptcy process. Filing in Delaware allowed companies that were functionally based elsewhere to “escape the obligation to make the process open,” as Warren put it.

Bankruptcy cases made huge gobs of money for Delaware’s legal industry. When reformers introduced language that would force companies to file for bankruptcy in the states where they were actually based—a clause dubbed “the Delaware killer”—Biden used his leverage to defeat it. Ultimately, Biden ended up securing funding for four more bankruptcy judges in Delaware.

Over time, Biden’s exertions on the bankruptcy bill began to shape his national reputation. “His energetic work on behalf of the credit card companies has earned him the affection of the banking industry and protected him from any well-funded challengers for his Senate seat,” Warren wrote in the Harvard Women’s Law Journal. “This important part of Senator Biden’s legislative work also appears to be missing from his Web site and publicity releases.”

Warren’s criticism of Biden came to a head at a Capitol Hill hearing in 2005, when they sparred over the bankruptcy bill for 15 minutes. Biden appeared exasperated with the expert witness sitting across from him. He found it “outrageous” that she would question the openness of Delaware’s bankruptcy court to small creditors, and he insisted that Warren was aiming at the wrong target. Her focus should be on big structural issues like health care and lending practices, he insisted, rather than the particulars of the bill he was pushing:

Biden: Maybe we should talk about usury rates, then. Maybe that is what we should be talking about, not bankruptcy.

Warren: Senator, I will be the first. Invite me.

Biden: I know you will, but let’s call a spade a spade. Your problem with credit card companies is usury rates, from your position. It is not about the bankruptcy bill.

Warren: But, Senator, if you are not going to fix that problem, you can’t take away the last shred of protection from these families.

Biden: I got it, okay. You are very good, professor.

Biden takes criticism of his bankruptcy position personally, in part because it infringes so directly on his well-cultivated political identity—a middle-class warrior and longtime critic of corporate campaign contributions. In a floor speech just before the bankruptcy bill’s passage, he accused its opponents of “fabricating wild claims” such as the charge that the bill would make it harder for women to collect child support payments from insolvent ex-husbands. The bill did include protections for the collection of alimony and child support—pushed by Biden and endorsed by the National Child Support Enforcement Association—which moved those debts to the top of the pecking order (above credit card bills) in bankruptcy proceedings. In theory, this would save single parents and ex-spouses from having to hound deadbeat exes in court. But the criticisms weren’t unfounded either—by increasing the amount of money that companies with liens could skim off the top prior to bankruptcy, it shrank the overall pot of money to collect from. Henry Sommer, president of the National Consumer Bankruptcy Rights Center, says the idea that Biden stood up for single mothers is “kind of a hoax.”

“Vice President Biden has championed the middle class for his entire career and has a proven track record of delivering on his progressive values,” his spokesperson Michael Gwin said in a statement in response to questions about the bill. “As a Senator, Joe Biden fought to secure critical concessions for working families in the bankruptcy bill.” Biden did advocate for other improvements that made it into the bill’s final version, such as new disclosure requirements for credit card solicitations. The means test at the heart of the law came with a “safe harbor” provision that exempted filers who made less than their state’s median income. And Biden supported a cap on how much money a rich debtor could shield from creditors in the form of real estate.

When the New York Times Magazine asked Biden about bankruptcy reform in July, he was defiant. Contributions from banks didn’t matter to him, he said, because “MBNA could not beat me.” He had worked on bankruptcy reform, he explained, because he knew it was going to pass and he believed he had an obligation to use his influence to make it more consumer-friendly. “I had an opportunity to do one of two things: Vote no, and feel real good about it, or I could make it better.”

But the reform movement was hardly a steamroller. It took five successive Congresses, and a new president, to finally pass the bill in 2005. Plenty of Democrats in Washington, including then-Sen. Barack Obama, opposed it. Biden’s support was instrumental, and he was deeply invested in its success. “If they don’t [pass it], to hell with them,” he reportedly said of his colleagues in 2002, after the bill stalled yet again. Those weren’t the words of a person who was simply along for the ride. Biden joined a small group of Democrats representing major credit card states to vote with a united Republican bloc against Democratic amendments aimed at moderating the bill’s pro-creditor slant.

No one I spoke with who opposed the bill considered Biden sympathetic to their side. Gary Klein, a former senior attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, which had helped coordinate opposition to the bill, told me his coalition never even got a meeting with the senator or his staff despite repeated requests.

The bankruptcy bill did not, in retrospect, turn into the total catastrophe that its opponents had feared. Senators introduced enough changes that the final version included protections for certain kinds of debtors from certain kinds of creditors. “I think over time that some of the balance we got into the bill has proven effective at allowing people who need the system to get the relief that they need,” Klein said. But, he added, “I still don’t think it was a good bill.”

A 2008 study published in the American Bankruptcy Law Journal found that “credit card companies saved billions because of reduced loan loss rates,” but that none of those savings benefited consumers. Because interest rates and late fees continued to tick upward, “the cost to credit card customers increased 5% to 17%.” And even before the recession hit, Credit Suisse found that the bankruptcy law had “a profound impact on subprime borrowers” and made it more likely that borrowers would fail on their bankruptcy payment plans. “Before that law was passed you could file a chapter 7 bankruptcy for seven, eight, nine-hundred dollars, including attorney’s fees and filing fees, and that’s gone up to more like $2,000,” Sommer said. “It’s made bankruptcy much more expensive, difficult, burdensome, and less effective.” The number of personal bankruptcy filings has fallen by half in 15 years.

Biden’s banking votes have stuck with him because their effects have stuck with us. You could draw a reasonably straight line from the bank deregulation votes of the ’90s to “too big to fail,” the housing crisis, and the Great Recession. And plenty of Democrats do. Biden now finds himself locked in a tough presidential primary with Warren herself, who forged her political identity by clashing with the kinds of megabanks Biden had a hand in creating. At an event in Iowa this spring, Warren used the bankruptcy showdown as a point of contrast between herself and the Democratic frontrunner. “I got in that fight because [families] just didn’t have anyone and Joe Biden was on the side of the credit card companies,” she said. “It’s all a matter of public record.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders, another critic of Biden’s banking votes, sometimes asks audiences to rattle off their student loan debts. But Biden, whose state is home to student lenders like Sallie Mae and Navient, cast vote after vote to make student loan debt as hard to escape as credit card debt. Sanders has pushed to cap credit card interest rates at 15 percent and called for the return of Glass-Steagall, whose repeal, he warned in 1999, would put taxpayers on the hook “should a financial conglomerate fail.” In August, he proposed canceling all of Americans’ overdue medical debt (about $81 billion) and repealing portions of the bankruptcy law, which his campaign said “eliminated fundamental consumer protections.”

In 2008, the New York Times reported that Obama aides considered MBNA “one of the most sensitive issues they examined while vetting [Biden] for a spot on the ticket.” Biden’s progressive critics still harbor those concerns. “We saw in 2016 that there were too many people who bought Donald Trump’s fake populism where he pretended to bash Wall Street and pretended that he would clean up corporate corruption and political corruption,” Adam Green, co-founder of the Warren-backing Progressive Change Campaign Committee, said. “We can’t blur the waters on that again. We need to have someone who voters instinctively see as on their side and willing to challenge entrenched interests.” The economic system Warren and Sanders are running against is the one that Biden helped export from his state to the rest of the nation.

Like most of the institutions that call Delaware home, Joe Biden now does much of his work somewhere else. His campaign is headquartered in Philadelphia. His campaign kickoff was in Pittsburgh. His stump-speech lodestar is Scranton. But if its elder statesman has moved on, Delaware hasn’t.

One afternoon in July, I strolled from the Joseph R. Biden Jr. Railroad Station in downtown Wilmington and walked through the leafy JP Morgan Chase campus to the gleaming new Delaware Chancery Court. A few blocks north, the Hotel du Pont still stands, flanked by the 18-story Citizens Bank and a high-rise that until recently was owned by Bank of America, which purchased MBNA for $35 billion in 2006. The old chancery court has a new tenant too—the state’s largest bankruptcy law practice. The names may change, but the Company State is eternal.

On my way back to the station, I stopped at the Delaware History Museum, a tidy space that opened its doors in a renovated Woolworth in 1995 amid a boom in downtown construction. There, alongside artifacts from DuPont’s labs and a T-shirt from the Punkin Chunkin Festival, was an entire exhibit on the modern Delaware economy. A black-and-white photo depicted the supermarket where MBNA opened its first office. Accompanying text helpfully explained how the 1981 Financial Center Development Act removed “the cap on the interest rates that banks could charge on credit cards…further diversifying the state’s economy.” Wall panels, at kid-level, invited visitors to guess the identity of Delaware-incorporated companies based on short descriptions like “This company’s mascot is a charming green Gecko with a Cockney accent who turns up everywhere in television commercials.”

I wandered out to the gift shop, where I found the bestselling item perched on a shelf along the back wall. “Your long search is finally over,” a sign said. “You have acquired a Joe Biden scented candle.” It cost $22 and smelled like oranges. Before you ask, yes, they take credit.