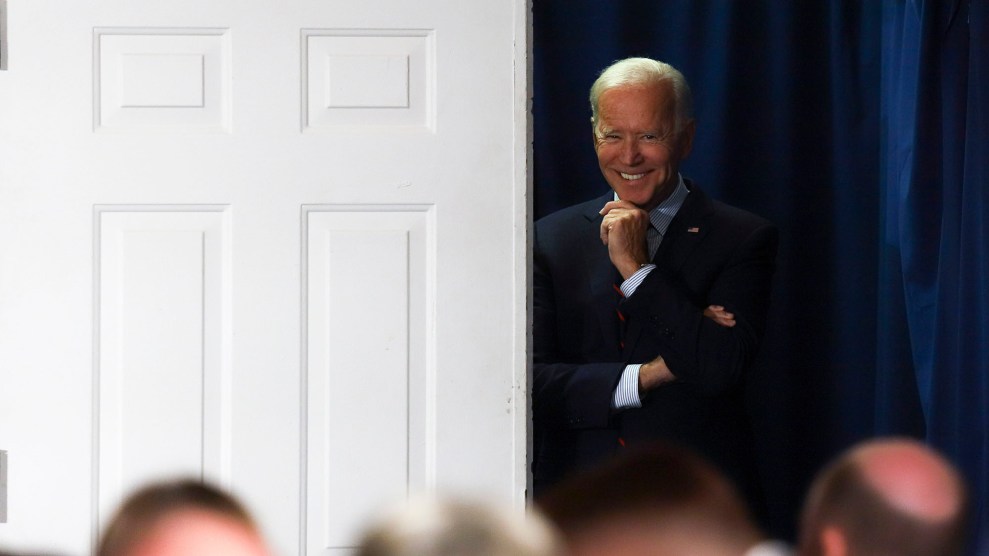

Democratic presidential candidate and former vice president Joe Biden speaks at a campaign event in Scranton, Pa., on October 23, 2019.Matt Rourke/AP

On October 20, Joe Biden rode into the well-heeled suburb of Greenwich, Connecticut, to attend a high-dollar fundraiser hosted in his honor by the state’s governor, Ned Lamont. The event was sandwiched between appearances in Manhattan, suburban Westchester County, and a swing through Pennsylvania, where the former vice president headlined another pricey event in advance of a speech in his hometown of Scranton—a speech that made an emotional appeal to the economic plight of the middle class.

The campaign wouldn’t disclose how much money the event at Lamont’s personal mansion raised, but the Hartford Courant reported that 140 attendees had chipped in more than $300,000—meaning at least three-quarters of donors had paid the $2,800 maximum campaign contribution that federal campaign laws allow. The former vice president had arrived from Manhattan by car and departed the same way, with no public or smaller dollar events as part of this trip.

Biden’s been at the top of the national polls since he entered the 2020 fray, but his fundraising numbers haven’t reflected that. From July through September, Biden posted $15.7 million, nearly $2 million less than what he spent during that time. His chief Democratic rivals, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, outraised him last quarter—by $12 million and $9.4 million respectively—while eschewing events like the one Lamont hosted. They are each declining to hold high-dollar fundraisers and are raising money primarily with low-dollar online contributions.

Critics and fans of Biden alike have noticed that his campaign has become overly reliant on exclusive events for the upper-tier of Democratic donors, and have suggested that the former VP might want to gin up some enthusiasm with the middle class voters who can chip in smaller amounts. They say private gatherings with lower price tags or public appearances paired with the opportunity to donate—a ritual of the Sanders and Warren campaigns—could cultivate the demographics and bring in some much-needed cash.

But instead, Biden’s finance team is taking the opposite approach, pushing the campaign to be more reliant on max donations, by setting higher benchmarks for fundraisers that Biden will attend and keeping the candidate away from events with lower ticket prices. Biden supporters in close contact with the campaign told me they have faith in Biden’s tactics, but wouldn’t mind seeing the former vice president take a page or two out of his rivals’ handbook and pair these high-dollar appearances with small-dollar stuff that both pads the coffers and builds grassroots-style rapport with a different swath of the electorate.

A Politico analysis of candidate schedules found that Biden dedicated more than a third of his campaign schedule from April through August to fundraiser appearances, a percentage bested only by California Sen. Kamala Harris and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg. Biden’s appearance in Greenwich is one of at least half a dozen high-dollar fundraisers he’s held since the October 15 FEC filing deadline, where plates started at $1,000 and ran up to $2,800—and would-be donors willing to fork over the lower sums were turned away in favor of those who could dish out the max. (The Biden campaign declined to comment on details in this story.)

And Biden finance staffers have encouraged higher thresholds for these big dollar events: In the tri-state area of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, hosts have been asked to hit a goal of $200,000 per event, a floor $50,000 greater than what had been asked in past months. The campaign is rewarding bundlers with titles like “advocate” ($25,000) and “unifier” ($100,000) that come with attendant perks, like calls with campaign leadership and invites to finance committee meetings. And last Thursday, his campaign announced that it would no longer rebuff financial assistance from super-PACs, groups that raise and spend unlimited amounts of money. They tend to rely on massive checks from wealthy donors and offer another outlet for big spenders who have already maxed out in their donations to Biden’s primary fight.

Biden’s two top challengers, Sanders and Warren, have taken an opposite tack. Both have rejected corporate PAC donations, super-PAC help, and high-dollar fundraisers during the primary—and vow to continue doing so if one of them is chosen as the Democratic nominee. They’ve instead spent much of their time on the road, holding rallies and small gatherings that give them face time with supporters, in addition to the occasional in-person contribution—a method that’s also helped them build massive online lists that they can solicit from again. Sanders has held the occasional small-dollar fundraiser, like the one he did in Detroit in advance of the second debate. Both Sanders and Warren publicly criticized Biden for his reversing his position on accepting help from super-PACs.

In the early states, Biden’s public appearances do mirror those of his Democratic rivals, where campaign aides collect contact information and small donations from attendees. Jill Biden, the former vice president’s wife, has held lower-dollar events for her husband in Washington, Florida, Connecticut, and elsewhere, where the cost of attendance has hovered in the two- and three-figure ranges.

But some Biden supporters see the chance to do more events with smaller donors. “I wish we would do more unified events where you have high-dollar, medium-dollar, and low-dollar offerings,” says William Owen, a DNC member from Tennessee who has endorsed Biden. “I’m sure that will come. The campaign’s saying what their priorities are now and I respect that.” Owen co-hosted a top-dollar fundraiser at the Nashville City Club in May; hosts put up the maximum $2,800 donations while attendees paid $1,000.

“I believe in small money,” says Charlie Diradour, a Biden backer based in Richmond, Virginia, who’s in frequent contact with the campaign. “I think there’s some unique ways of raising money for those who can do $25, $100, $250. I don’t see what’s wrong with getting someone from the campaign on a phone or an iPad down here to do a presentation with beer and snacks. You don’t need Joe Biden or Dr. Jill Biden in the city to do that.”

Diradour held a fundraiser for Biden in August, where an invitation listed attendance prices ranging from $500 to $15,000. He says the Biden campaign has told him that it will be doing small money events at some point in the future. “I believe going forward, you will see more small money contributions into the Biden campaign,” he says.

Barry Goodman, a DNC member from Michigan and Biden supporter, co-hosted a fundraiser for Biden in Detroit around the second Democratic debate. “At our event, we were charging $1,000 per ticket, and for the maximum donation you got a photo,” he says. But he insisted the campaign offer a lower-priced ticket for attendees under 35, at $250. “I didn’t want just 50- or 60-year-olds. I’m trying to energize millennials who respond well to seeing Joe in person.” Ticket prices at similarly timed Sanders fundraiser in Detroit started at $27.

But none of the Biden boosters Mother Jones spoke with begrudge the campaign’s tactics. “I wish there were no PACs anywhere, anytime, but unfortunately to compete, they’re what you need,” Goodman says. “You have to trust who are running for office that they won’t be beholden to those.”