Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP

At the center of the most passionate infighting of the Democrats’ 2020 presidential contest so far is the much-ballyhooed Medicare for All proposal. Bernie Sanders hails the idea—which would expand the federal government’s health care insurance program for the elderly to everyone and replace private insurance—as part of the political “revolution” he champions. Elizabeth Warren, who has endorsed Sanders’ plan, has been pressed at multiple debates by moderators and other Democratic contenders to acknowledge it would raise taxes on middle-income Americans (while, in theory, lowering their health care costs by a greater amount). Her refusal to do so has drawn criticism and barbs, as her Democratic rivals, including Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg, have questioned the total cost of such a program and decried the notion of taking away existing insurance from the two-thirds of Americans who have private health care plans. Recently, Sen. Sherrod Brown, the feisty Democratic populist from Ohio, who opted not to join the 2020 fray, noted, “It’ll be a hard sell to the public if we go into the general election for ‘Medicare for all.’” He cited the risk of alienating union workers who would lose their plans.

Whether they know it or not, the Democrats, on this front, are really fighting over economic theory, and the bad news for progressives is that social science research is not on the side of those calling for sweeping and immediate change in an industry that makes up about one-fifth of the US economy.

The traditional arguments against Medicare for All are hardly surprising: a gargantuan price tag, expanding government power (socialism!), widespread disruption, and so on. A big change to the status quo—especially a system that is profitable for many—will draw big opposition from the established order. But it does not take a rocket scientist—or a neuroscientist—to understand a basic dynamic that could put off voters. This proposal promises great benefits—no co-payments, no deductibles, low-priced medication, and more—in return for higher taxes, with the financial gains for consumers surpassing the cost of the tax hike. Yet it is not difficult to imagine that many voters will assume that the government will raise taxes (it certainly knows how to do that) but wonder if the government will be able to deliver on the promises of lower health costs and better treatment. (Progressives have long had to contend with an internal conflict in their overall message: Government is a corrupt institution shaped by corporate interests, and the power of government should be widened to address social ills.) And if a known quantity (your existing health care insurance, as imperfect as it may be) is going to be taken away and replaced by an unknown (the promised better system), many voters may be hesitant to make the swap. The devil you know and all that.

This mindset is a fundamental aspect of human nature, according to the pioneering work of behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. In 1979, the two developed what’s known as the prospect theory. It’s one of the first economic theories derived from actual experiments, and it challenged the basic notion advanced by classical economists that people evaluate decisions in a pure gain-versus-loss manner. No, Kahneman and Tversky said, after conducting a series of studies with people: Human beings are not that rational—or, that is, not rational in that way. People assess loss and gain in an asymmetric fashion. And that’s a problem for Medicare for All advocates.

In his marvelous 2011 book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2002, notes that “loss aversion” has an outsize impact on a person’s decisions: “When directly compared or weighted against each other, losses loom larger than gains.” So the prospect of losing what you have (say, your existing insurance) weighs heavier than the prospect of obtaining something better (no-cost insurance that supposedly will cover more). Kahneman explains there is a sound reason for this: “This asymmetry between the power of positive and negative expectations or experiences has an evolutionary history. Organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce.” Bottom line: We’re generally hardwired more to worry than to hope.

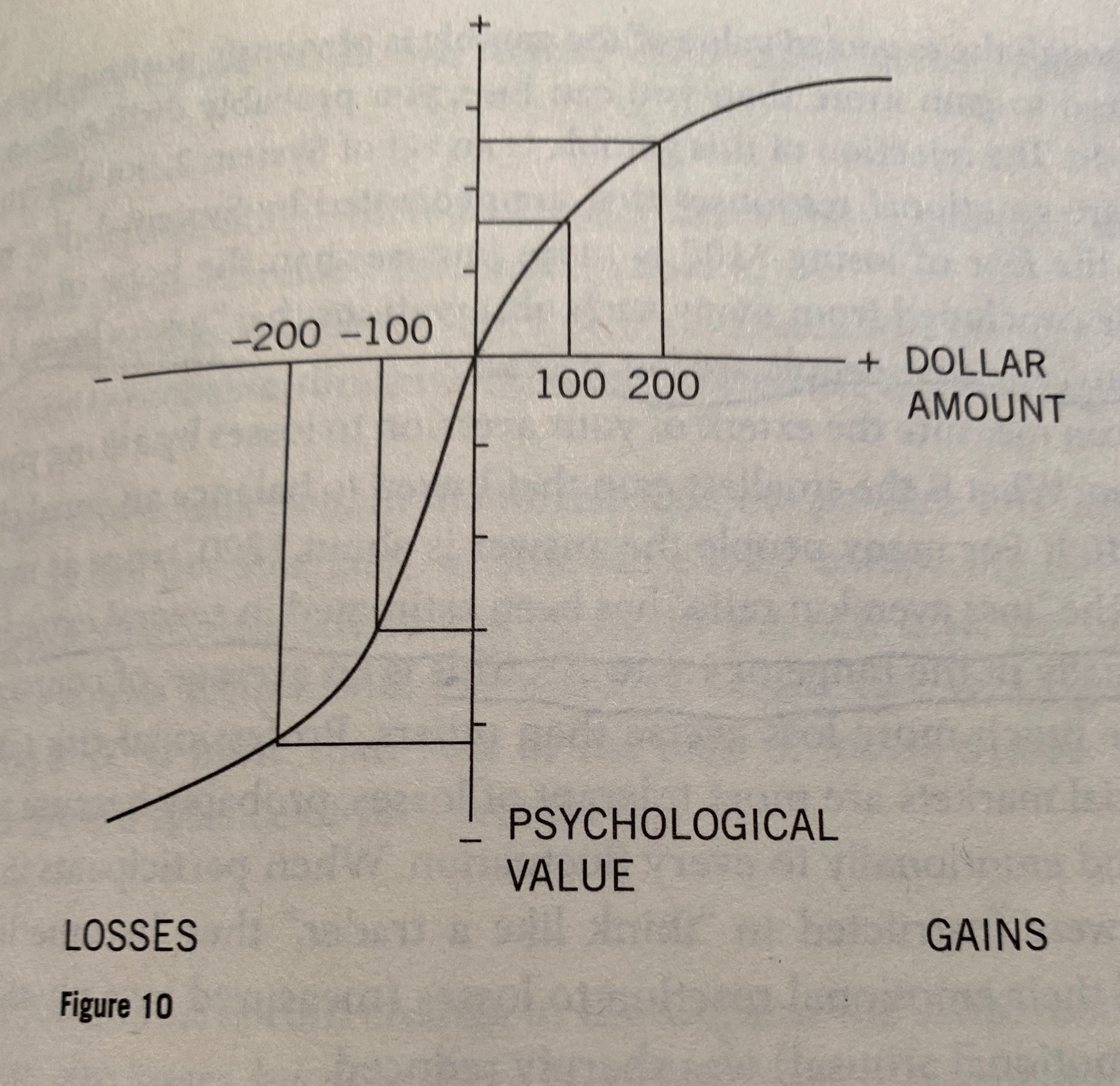

Kahneman and Tversky created what Kahneman calls a “flag” for their prospect theory with this chart:

The vertical axis measures the psychological value of the loss or gain, and it demonstrates that losses affect us more greatly than gains. “The response to losses is stronger than the response to corresponding gains,” Kahneman notes in Thinking, Fast and Slow. And he adds that “loss aversion rates” are “usually in the range of 1.5 to 2.5,” meaning the possible gain has to be worth 1.5 to 2.5 times as much of the possible loss for a choice to be seen as an even bet. And that’s when the two possibilities can be clearly articulated.

“Many of the options we face in life are ‘mixed’: there is a risk of loss and an opportunity for gain, and we must decide whether to accept the gamble or reject it,” Kahneman writes in his book. Medicare for All fits that bill for many. For those Americans with no health insurance coverage or with the crappiest plans, there will be little or no loss aversion. But a large majority of Americans are being asked to forego what they have for the promise of a plan that is supposedly better for them—and the nation at large. It’s understandable that when the choice is presented this way, they may be less than eager to dive in. Kahneman and Tversky’s theory shows why. (There’s another element not covered by the theory that is also crucial: Whether voters have confidence that whoever is proposing this radical restructuring has the ability to make it happen and then make it work. A voter can love Sanders’ plan but question whether he has the skills necessary to get it through Congress and guide the federal government to implement it effectively.)

The prospect theory is not the be-all and end-all. Kahneman notes it has flaws. For instance, it fails “to allow for regret.” But it does illustrate a problem faced by Medicare for All fans and those who would make this idea a litmus test for candidates or progressives at large. A candidate who champions a proposal that removes an existing benefit faces an uphill battle. Which is why polling shows that a plan that expands Medicare to cover people who want it and that does not force Americans with private insurance into a public health insurance system is more popular (at 67 percent in one recent poll) than the Sanders-style Medicare for All that eliminates private insurance (at 56 percent). And keep in mind, such polling has occurred in an atmosphere in which the mandatory loss of your private insurance is just starting to become an issue in the Democratic campaign. Though the health care discussion during the recent Democratic debates has frequently been chaotic and confusing, Sanders’ and Warren’s foes have tried to zero in on this aspect of the plan. (Warren recently announced she would within weeks release her own health insurance plan.) And it’s easy to conceive of a campaign that could be whipped up against a Democratic candidate advocating Medicare for All that hammers on the well-defined loss and questions the possible gain. The forces behind such an attack—Donald Trump, Republicans, corporate interests, Big Insurance—would be, whether they know it or not, relying on the prospect theory.

Remember how President Barack Obama claimed the Affordable Care Act would allow consumers, if they like their doctors and plans, to keep them? That turned out to be not entirely true—and he was mightily slammed for that. Many of the large and small social reforms that have succeeded in the United States—Medicare, Social Security, the Children’s Health Insurance Program—provided new and additional benefits to American citizens, without taking anything away. Medicare for All does both. That doesn’t mean that the trade-off (ending private insurance in return for a national public system) is bad. But this grand deal does create a political burden for those promoting this reform.

Selling massive and immediate transformation is a tough job—especially when it requires people to give up what they already possess and have become accustomed to. It’s incumbent on any would-be reformer to have a clear-eyed understanding of how voters will process the choice. A good idea is not enough. Neither is a bold promise. The numbers have to be convincing—and the psychology, too. Hope, optimism, passion, and public interest values can all be called into action. But Medicare for All proponents must realize that the arc of human decision-making seems to bend toward loss aversion—and that means they will need to find their way up this steep slope.