Bill O'Leary/The Washington Post/Getty

This story was originally published by Slate and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

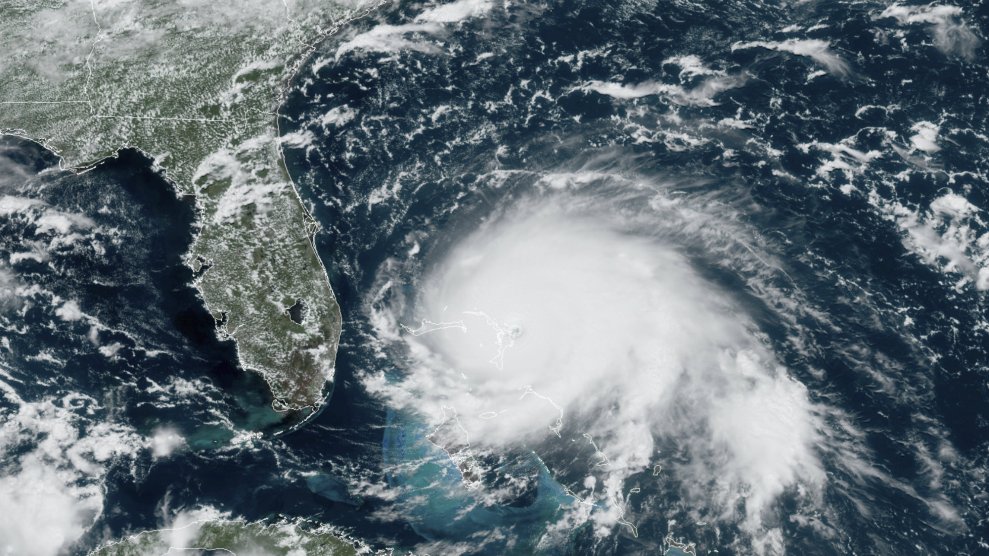

Official warnings about Hurricane Dorian, which continues on its tight-spinning crawl along the Southeastern US coast, have now been supplemented, underscored, and bungled by the nation’s president. Amid the chaotic weather reports emanating from his mouth and Twitter feed, Trump has already mistakenly declared that the storm endangers Alabama, misattributed a request for emergency relief in North Carolina, and gone to weird lengths to ballyhoo and exaggerate the storm’s historical significance.

This interference with the spread of useful information is as mystifying, in its way, as it is annoying. This administration and its leader have proved willing to display a floundering disregard for almost every form of technical expertise over the past few years. But still, one might hope that an exception would be made when it comes to weather forecasting. This White House isn’t known for being overstocked with scientific experts, but it does happen to have extraordinary and surprising depth in the field of meteorology. So why not use it?

In February, for example, the Trump administration booted the acting head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Timothy Gallaudet, in favor of Neil Jacobs, an expert in…weather forecasting. In choosing a meteorologist to run NOAA, Trump broke with a decades long tradition in which marine scientists like Gallaudet or space experts filled that role. Jacobs is the first weather guy to run the agency since 1977.

In taking the role, Jacobs joined another highly respected weather modeler in the upper echelons of the nation’s science bureaucracy. Last summer, Trump named the extreme-weather forecaster Kelvin Droegemeier as his director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy. Since most presidential science advisers have been physicists or engineers, it seemed like Trump was maybe making a point in bringing on a world authority on tracking storms—something like a meteorologist in chief for America, who could help the White House improve its shabby handling of hurricane emergencies.

The fact that we have such a deep bench of weather expertise in Washington only makes this week’s Oval Office clown show more depressing. I realize that Jacobs and Droegemeier shouldn’t really be the government representatives to answer questions on TV, or tweet out the best advice and information on a storm. Still, in the context of this image-first administration, I can’t help but rue the absence of their expertise in public settings. Droegemeier, in particular, could be far more involved in White House messaging on Dorian. After all, he isn’t just a very well-credentialed scientist and a founder of the Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms (though that alone would qualify him to speak out on the topic). Droegemeier also happens to be what the president might call a weather nerd “from central casting.” Bespectacled and big-eared, he’s a meteorologist named Kelvin who collects vintage handheld calculators and says he fell in love, as a teenager, with the power and majesty of tornadoes. If Trump can’t or won’t march this guy out for television briefings on a dangerous storm, what was the point of bringing him to Washington?

“That’s not his job,” University of Washington meteorologist Cliff Mass told me earlier this week, in reference to Droegemeier’s absence from the White House weather updates. “Kelvin should not be out there communicating the forecast.” Yes, of course that’s right. In a perfect world, this sort of messaging about a hurricane would be left to proper sources at the National Hurricane Center.

This is not that world.

It’s not as though Droegemeier is doing that much else with all his weather expertise. When he was appointed, some prominent scientists expressed relief at having a storm expert so close to the Oval Office. It’s very important to draw connections between extreme weather events and climate science, one former presidential science adviser told Nature in August 2018, and “there’s nobody better to do that than Kelvin Droegemeier.”

Yeah, well. When the science adviser gave a speech about his main priorities at the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in February, shortly after he’d been formally confirmed for his role, Droegemeier made no mention of climate change. In a follow-up interview with Science, he professed to have insufficient mastery of the facts. “I’m not a climate scientist,” he said to a reporter, indulging in the now-infamous formulation, “and my work [as a meteorologist] is actually at the opposite end of the spectrum.”

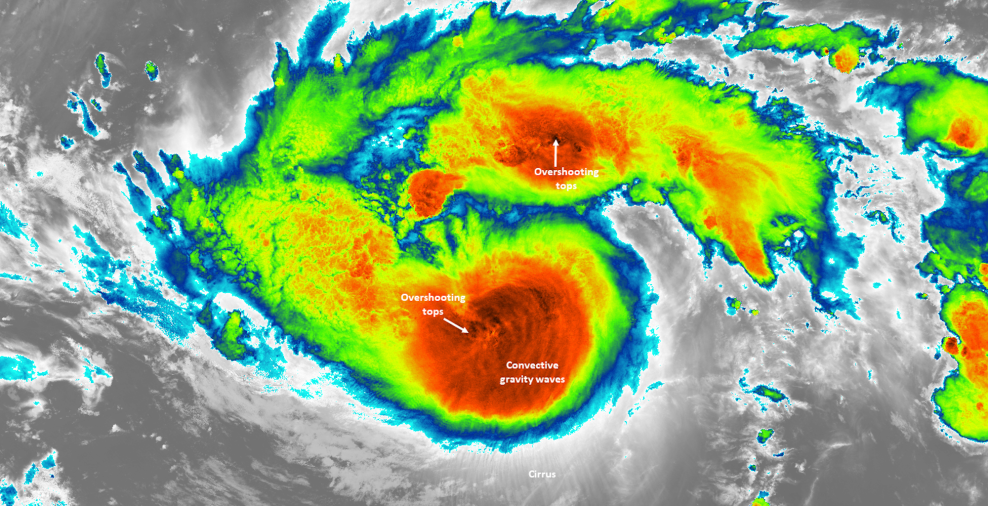

Let’s put to rest the fantasy that Droegemeier will teach the president about the links between climate change and extreme weather. No one in the world is getting through to a guy who tweets “where the hell is global warming?” whenever there’s a cold snap and relies on his “natural instinct for science” on the topic. Still, as Droegemeier himself points out, meteorology is distinct, in lots of ways, from the study of the climate. (You need a very different kind of model to guess the amount of rain in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, tomorrow than to predict average temperatures around the world in the year 2100.) And while our government may be flubbing its analysis of long-term, global trends, there’s every reason to believe that we’re in a golden age of government support for weather science.

In fact, in contrast to the crazy-making battles over global warming, there’s been a recent push by Democrats and Republicans alike to strengthen and improve the nation’s meteorological resources. This project started in earnest after 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, which produced, amid its devastation, a significant anxiety over the sad state of US storm forecasting. It turned out that American weather models and supercomputers had lagged four days behind their European counterparts in successfully predicting the hurricane’s fateful turn toward New York and New Jersey. By 2013, both parties in Congress were working on a comprehensive plan to fix systemic problems with the nation’s weather prediction.

This project culminated shortly after Trump took office, with his signing of the Weather Research and Forecasting Innovation Act in April 2017. Since then, his administration has continually requested appropriations in support of weather science research even while suggesting cuts to science budgets elsewhere. Trump’s latest budget request, for 2020, proposed an 18 percent cut to NOAA’s funding overall, including a 45 percent cut to its climate research. But tucked amid the details was a recommendation that $15 million be appropriated for a new “virtual center” that’s meant to bring US weather models up to the level of our rivals’, in support of the goals laid out by the Weather Research Act.

Congress, for its part, has been even more aggressive about putting money into meteorology. For the 2018 budget, legislators increased the total budgeted for weather research by one-sixth, to $132 million. The following year, it added another 3 percent.

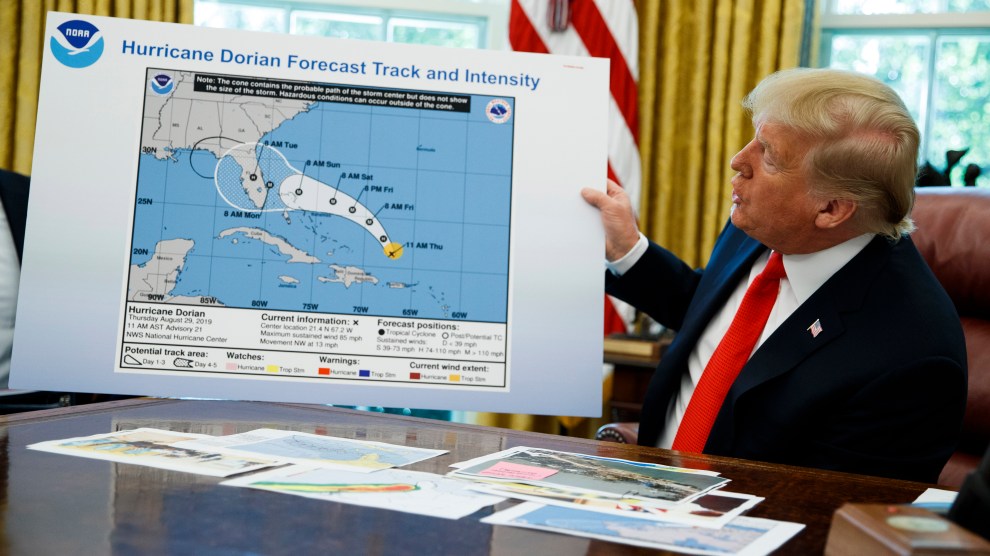

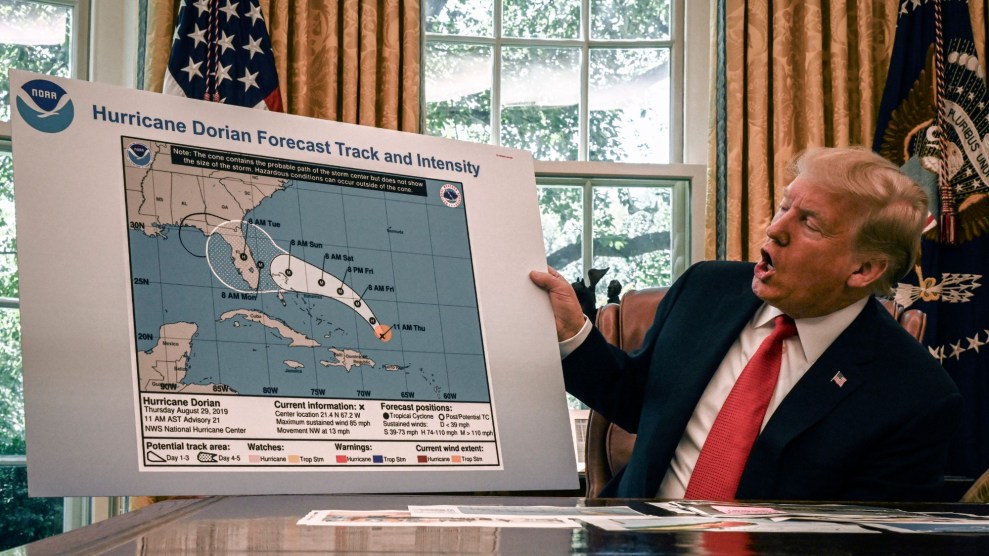

That’s why meteorologists like Mass have been feeling optimistic. “The head of NOAA is a weather modeler, and the president’s science adviser is a weather modeler,” he said. “It’s not only that you have those two people in place—Congress is in on it, too. There’s a tremendous opportunity right now to fix some of the fundamental flaws with weather prediction.” And yet, rather than seeing the fruition of this work, we’re getting oak-tag storm maps on TV that look like they’ve been altered with a Sharpie.

I’m glad the science is improving in the background. But as Dorian bears down on our shores, it’s worth remembering that somehow, and in spite of everything, our feckless and incurious commander has managed to recruit a brilliant team of experts on the weather. In the coming days, and in the face of life-threatening inundations, maybe it would be nice to hear from them instead of him.