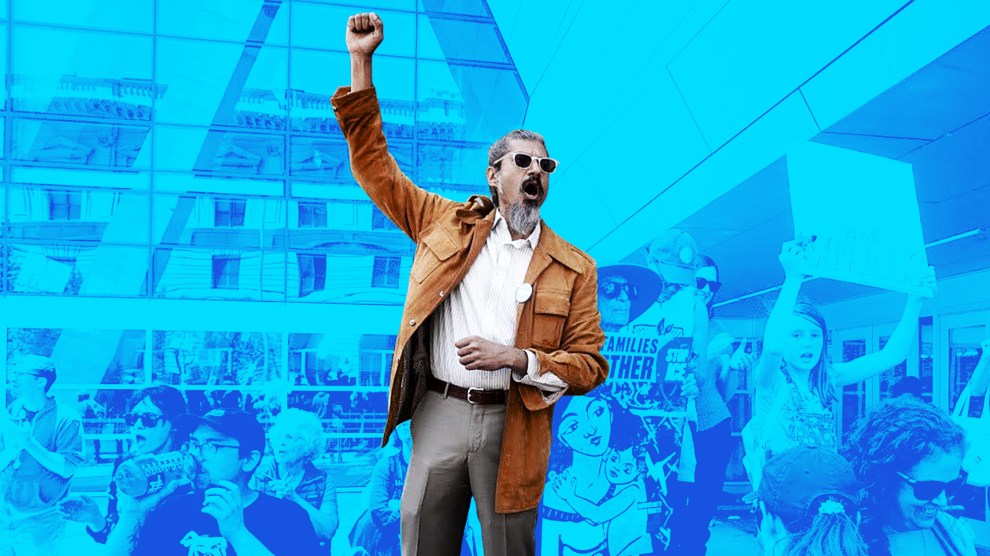

Courtesy Shahid Buttar for Congress

“I’m pretty sure,” says the man running to unseat Nancy Pelosi, “I am the only congressional candidate in the history of the republic who has spent time at Burning Man rhyming about the climate crisis and police violence and the role of immigrants in our community.” Shahid Buttar is laughing a little. He knows how it sounds. He knows there are people around the district who think of him as “that guy who goes to Burning Man,” which for the record he considers a space for “profound personal transformation” and “a hot bed for organizing.”

“I get the same thing about my hair,” says Buttar, who wears his salt-and-pepper hair in a top knot. “I’m too hipster for some people, I guess. But you know, I’m running to represent San Francisco, not Texas. And I couldn’t care less about the conservative stylistic sensibilities of a generation that, frankly, we’re trying to overcome.”

He’s talking about Pelosi. One of the premises of Buttar’s long-shot candidacy is that he’s more in tune with the district’s character than the speaker of the House is. Pelosi has spent much of her 17th term squabbling with the left flank of the Democratic Party and avoiding an impeachment showdown with President Donald Trump. Buttar’s proposition is a dubious one—no one gets to a 17th term without knowing something about her district, and in fact Pelosi has quietly shored up her support among the progressives who control the local Democratic Party, closing off one potential access point for an insurgency. If Buttar has a natural constituency right now, it’s not San Franciscans, at least not in the main; it’s the people around the country who see Pelosi as a quisling centrist party boss who’d sell out every refugee in Juarez for a few points in a swing-district Gallup poll. As Buttar puts it, “Her M.O. is creating space for conservative interests while claiming to defend whatever vestige of liberalism she remains committed to.”

Buttar does lay claim to certain distinctly San Francisco traits. The 44-year-old is an activist and a dabbler, and his politics are intertwined with his personal interests in such a way that it’s hard to know where the former end and the latter begin. He is a civil rights attorney and a grassroots organizer; he is a Burner and a Berner and a rapper, too. It’s funny: In a very rough sense he is the person the right wing believes Pelosi to be—the wild-eyed libertine crusader for “San Francisco values.” “I’m a post-colonial, intersectional liberation agent,” he says with a smile but no apparent irony. It’s not a soundbite. You won’t see that on a yard sign. But in a way, this, too, is a premise of Buttar’s bid to take down Pelosi, high priest of the DC cult of the savvy: Maybe it’s time for a little unsavvy.

As we walk around the city’s Civic Center neighborhood, I ask Buttar if there’s a song of his that best represents his campaign.

“Sure,” he says. “I have a music video called ‘NSA vs. USA,’ which I invite you to check out.” He says it’s a “hip hop–house music lesson” centering on President Eisenhower’s warning about the military industrial complex and “how it relates to police militarization and surveillance and the FBI’s attack on Martin Luther King and the Edward Snowden revelations, and how all that remixes and connects.” He has another on Guantanamo and what he sees as “the bipartisan endorsement of torture and what that means to the legacy of human rights.” And there’s “Ferguson to Jerusalem.” “It basically is a rhyme that connects the uh—well, I’ll just spit you the first verse and you’ll get a sense of it,” he says.

We cross the street, and he recites the first verse in a flat monotone:

There’s a Mike Brown in every town

Don’t try to tell me that America was found

We’ve been slaughtering innocents from the very beginning

our country spits a big game while sinning

Now he’s rolling. He keeps going:

Spitting half-ass facts:

All men are created equal,

except apparently blacks. Folks got

declared three fifths when whites wrote the Constitution

and ever since then even it we keep abusin’

Mass confusion on our own stated principles

Leaves the empire seeming invincible

Murder with impunity when shot by a cop

while prosecutors persecute the block nonstop

All the way from Ferguson to Jerusalem

the criminals have badges

From Ferguson to Jerusalem

To Washington, Houston, we have a problem

For housing, education not enough funds

’Cause we give the real criminals badges and guns

He stops abruptly. “You get the sense, right?”

Buttar is the director of grassroots advocacy at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which promotes and defends civil liberties on the internet. EFF’s most recent big win was getting facial recognition technology banned in San Francisco, a project Buttar has been working on in cities throughout the country. But his activism dates back nearly two decades. As a student at Stanford he helped organize anti-war protests in San Francisco. He founded a “poetry convergence” to serve as “a training ground for poets to learn how to claim public space and hold it, to basically share political propaganda.” His first case out of law school was defending campaign finance reform, four years before the Citizens United decision. In 2004, he filed the first marriage equality case in New York, and in 2006, while working at the American Constitution Society, he fought Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the DC circuit. “At the time, we were fighting all of Bush’s nominations,” he says. Later, at Muslim Advocates, he founded the program to combat racial and religious profiling. From 2009 to 2015, he led the Bill of Rights Defense Committee, a civil liberties group.

“I’ve been at this stuff a long time,” Buttar says. He is running not so much because he has “aspirations” of holding office, he tells me, but because he has many “deep frustrations”—one of them being Nancy Pelosi.

We’d met earlier in the day in front of the San Francisco Federal Building, where Pelosi keeps her district office and where a group of maybe 60 people, mostly women and children, had gathered to protest one of Pelosi’s latest outrages. This was July 1. Senate Republicans had just crafted an emergency spending bill that, with almost no congressional oversight, would funnel billions of dollars to the Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Pelosi vowed to hold strong against it, and then she didn’t, infuriating the progressive wing of the Democratic Party for what they saw as yet another capitulation to Trump. (In truth, it was a capitulation to the so-called Blue Dog Democrats, the centrists who knuckled Pelosi into dropping a House version of the bill that included protections for migrant children.) One protester’s sign got straight to the point: “Pelosi, no compromising with fascists!”

Buttar was not at the protest in any official campaign capacity. “I don’t want to roll up here as a political candidate and hawk my wares,” he says. “It seems too pandering.” But wherever there is a group of people gathering to express contempt for San Francisco’s elected representative, there will also likely be Shahid Buttar. “I resisted Bush’s wars, I resisted Obama’s surveillance, I resist Trump’s concentration camps, and unfortunately I have to resist Pelosi’s complicity,” he tells me.

Buttar maintains a comprehensive rap sheet on the incumbent—and on his points of contrast with her. There’s her Trumplike position on Venezuela. The monthslong battles over whether to launch impeachment proceedings, with Pelosi falling decidedly on the “no” side (he “practically self-impeaches” daily, she said not long ago, as if that relieved the burden of formal impeachment). The constant dustups with first-year Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts, known collectively as the squad (all of whom backed her for the speakership). In June, Pelosi cut progressives out of a prescription drug pricing deal, which some say “goes easy” on Big Pharma. Six months earlier, she rammed through PAYGO, a Republican austerity provision demanding that any spending on social services be offset by corresponding tax increases or spending cuts in other areas, effectively knee-capping liberal wish-list items like Medicare for All and the Green New Deal. “Terrible economics,” Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, called the move. Buttar describes it as “discriminatory accounting rules that privilege military industrial complex spending over spending on issues like affordable housing, or health care, or food stamps.” On Medicare for All, she’s “agnostic.” On the Green New Deal, she barely musters a shrug: “the Green Dream or whatever.” This, says Buttar, is even worse than what climate-denying conservatives do. “Ignorance can explain them. But Pelosi is not ignorant. She is sophisticated and unwilling...She is intelligent enough to acknowledge the science, so she’s not a climate denier, but she is a climate delayer, and to acknowledge the science and still choose to do nothing I think is worse than people who bury their head in the stand.” Then, of course, there was the border funding bill. As a Democratic staffer told Vanity Fair after the bill passed, “She has the power…and she made the wrong decision.” And that’s all within the past year. When Pelosi was voting to fund George W. Bush’s wars, Buttar was marching in the streets against them. When she was “complicit in facilitating CIA torture crimes by sweeping revelations under the rug,” he was organizing the resistance to it. (A CIA timeline revealed that Pelosi was briefed on enhanced interrogation techniques in 2002 and raised no objections.) “When a Democratic speaker of the House adopts Republican fiscal austerity rules, refuses to hold a Republican president accountable for his serial and continuing crimes, and supports a kleptocrat’s foreign policy, we can’t pretend that that’s meaningful opposition,” says Buttar.

Pelosi’s defenders tend to describe her as a pragmatic leader who holds her caucus together through incredible feats of vote counting. She’s a realist, they say, who won’t indulge in fantasy and prefers to labor toward incremental but tangible gains. (That these are traits largely hidden from public view is the whole point—only true DC insiders can appreciate the dark arts of political statecraft.) Some of the claims made on Pelosi’s behalf are no doubt accurate. She was instrumental in beating back the Republican push to privatize Social Security during President George W. Bush’s second term, rejecting the savvy-set consensus at the time that something had to be done to address the funding “crisis.” This was a crucial moment in the party’s shift away from the business-friendly Democratic Leadership Council era. In 2009 she pushed a cap-and-trade bill through the House (though the measure died in the Senate). In 2010 she shepherded the Affordable Care Act to passage, a remarkable legislative achievement that has withstood years of Republican sabotage.

Rep. Nancy Pelosi is greeted by moderator Gloria Duffy before speaking to the Commonwealth Club on May 29 in San Francisco.

Eric Risberg

But all this talk about Pelosi’s practicality begs the question of what gets reckoned practical or impractical in the first place. In the through-the-looking-glass morality of the DC political class, fantasy is opposing Trump’s ethnic cleansing altogether; realism is giving the president the money to fund it, lest certain swing Democrats appear too “pro-immigrant,” as one member of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus characterized it. Fantasy is wanting to exercise the House’s full practical means of oversight in the form of impeachment; realism is not wanting to do anything that might anger the people who aren’t going to vote for Democrats anyway. That Pelosi and her party might have some power to positively shape public opinion around their goals and values rarely seems to factor into the leadership’s calculus. The procedural moderation starts to look like an end unto itself. Perhaps, as HuffPost’s Zach Carter put it recently, she “doesn’t know who the Democratic Party is anymore.” Perhaps Buttar’s epitaph for Pelosi—sophisticated and unwilling—applies to more than just climate policy.

But is that how the putative progressives of San Francisco view her? Pelosi has been in office 30 years, swiftly and decisively dispatching her opponents in one reelection bid after another, including Buttar, who joined the 2018 race late and fell just shy of the second-place finisher in the primary, Republican Lisa Remmer. If Pelosi is truly the craven moderate Buttar says she is, what does that say about San Francisco?

There’s a difference between how the city votes at the hyper-local level and how it votes for higher office, such as Congress, says David Latterman, a San Francisco political consultant who typically works with center-left candidates. “When it comes to anything other than district races, we in this city really just don’t vote that way,” he says. “Look at our great politicians from this city—we crank ’em out like a factory: Newsom is not a hard lefty. Feinstein sure as hell isn’t. Pelosi is no longer. Kamala? She’s no progressive...We have a disproportionate number of people from San Francisco who do really well elsewhere, but none of them are on the hard left. All of our powerhouses are center-left, traditional liberal, even centrists.”

As for Pelosi specifically? “People revere Pelosi here. The woman who has been the biggest thorn in Trump’s side in two years? No one is going to vote her out of office.

“Dude, it’s Nancy Pelosi. End of story. That’s all there is to it.”

Jim Stearns, a progressive political consultant from San Francisco, sees a possible small opening for Shahid in the dynamics surrounding Pelosi and the squad. There are two other candidates in the March 3, 2020, primary—Agatha Bacelar and Tom Gallagher—and like Buttar they are mounting their challenges from Pelosi’s left. But Stearns sees little room for any challenger to maneuver. “By and large,” Stearns says, Buttar is “going to have a very difficult time. Nancy Pelosi is not just powerful but extremely well-known and well-liked by Democrats in San Francisco. Her numbers are consistently in the 70s and 80s. If you’re looking at it from a purely conventional political consulting point of view, you don’t see a lot of vulnerabilities there.”

Despite the persistent caricatures of San Francisco, the truth is that its politics look a lot more like Nancy Pelosi’s than Ocasio-Cortez’s. “This city is in some ways less the hardcore left progressive bastion you think it is,” says Latterman.

“It certainly was before,” Buttar counters. He points to Chesa Boudin, a progressive running for district attorney whose parents were members of the radical leftist Weather Underground. “I think precisely the question that’s on the table now with candidates like Chesa and I running to represent the city is: Can we make it that way again?”

Buttar’s version of San Francisco is the old ideal of the city: “There are several ways in which San Francisco’s particular voice has long been visionary—like being a mecca for the LGBTQ community, a home of the environmental movement, one of the more diverse parts of the country in terms of global representation, the tech industry and the creation of world-changing tools—this is a profound place and it always has been.” And, he adds, with a not-so-subtle nod to Pelosi’s decades-long reign, “It’s a voice that for the last 30 years has been entirely absent, the unique voice of this community has been entirely absent from Washington, and frankly the country needs our voice to be represented there.”

San Francisco may have changed, but Buttar believes there’s a native immoderation that, in theory, at least, should work against Pelosi. “I do think a lot of the folks who have moved here—the new entrants, the people who work in tech—they’re often derided as politically conservative because they’re upwardly mobile,” he says. “But many of them are very, very progressive, and very alarmed. Many others are very libertarian. But the point is: Very few of them are centrists.”

It’s hard to square Buttar’s notion of the San Francisco electorate with how it actually voted in 2016. During the Democratic primary, Hillary Clinton’s 85,000 votes in the city beat out Bernie Sanders’ 67,000. Says Stearns, “If you think of that as a proxy battle for this—and you have to say that Shahid is not Bernie; he doesn’t have the resources, he doesn’t have the awareness, he doesn’t have the people completely dedicated and loyal to him—it’s a real uphill battle for him.”

And just in case Pelosi does come under threat, she’s been preparing for it. In July 2017, David Campos engineered a progressive takeover of the San Francisco Democratic Party, cleaning out the real estate industry–backed and tech-funded “corporate Democrats who were running the show for many years,” in Campos’ words. When he became chair of the local party, he and Pelosi reached out to each other to work together in “a way that is unprecedented.” Last year, they launched Red to Blue SF, a volunteer call center aimed at flipping House control to the Democrats in the 2018 midterms. It was a “joint effort” between the local party and Pelosi, he says, “where she funded a lot of the space, the mechanics, and the operations, and then we staffed it.” They also aligned on a major ballot measure, Proposition C, that aimed to tax the wealthiest corporations in the city to fund homelessness programs. “It was opposed by the mayor, opposed by Big Tech and the Chamber [of Commerce],” Campos says. “The party came out for it…and then Nancy came out for it, too.

“This was Nancy Pelosi working with the progressive majority of the local party.”

While their politics differ at times, Pelosi can still count on Campos for support. “I am as aligned with the squad and AOC as anyone,” he says. “The question for me is, at the end of the day, who is going to move forward an agenda in the most effective way to address the needs of people like me? I believe that Nancy Pelosi is that person right now.” For a while, the banner image on Campos’ Twitter profile was a photo of him marching side by side with Pelosi.

“When incumbents just take for granted their position, that’s when those people are vulnerable, when they don’t take the potential for a challenge seriously,” Stearns says. “What I’ve seen from Nancy Pelosi is she takes those challenges very seriously, and she has been doing things to shore up her relationships with progressives in San Francisco to prevent a candidate like Shahid from getting a toe-hold.”

Buttar identifies a dormant radicalism in San Francisco politics, but he blames machine politics and money for its failure to awaken. Pelosi has “wielded her fundraising prowess and network basically like a sword of Damocles to intimidate potential opposition from people who might be inclined to challenge her,” he says, letting his critique outstrip his Greek mythology. “The people she’s faced in the past, and I have great respect for all of them, but they hadn’t necessarily had an opportunity to spend careers in public policy or public service. I’ve led a national non-profit. I’ve taught when I was still a student at Stanford Law. I spent 20 years building the progressive movement. I have a depth of experience and expertise that no one challenging her in the past had the opportunity to build.”

When Buttar characterizes himself as a “postcolonial, intersectional liberation agent,” it takes several minutes of explanation for me to understand him. “Postcolonial” refers to the fact that his ancestral land (Pakistan) had been dominated by a foreign power but also recognizes that he’s grown up with great privilege in the United States. His parents, belonging to the Ahmadi sect of Islam, fled Pakistan to escape religious persecution, landing in Britain before he was born. They left when Buttar was 2 years old to get away from the “postcolonial racism” they faced there. In America, he grew up in Rosebud, Missouri; attended Stanford; and worked, as he puts it, “in the imperial center” (Washington, DC) “for the liberation not just of the people from the place that I came from but all places.” “Intersectional,” by his lights, means he understands that people are oppressed across lines of race, gender, class, and nation of origin, and he knows how that oppression feels. “Liberation agent” means he’s fought to eliminate that oppression, however it occurs.

Call it activist cant if you want, but remember that there’s no shortage of political woo-woo surrounding Nancy Pelosi and her occult mastery over the levers of power. It’s just that, in the nature of things, the woo-woo gets alchemized into cold practicality, and the cant never gets a hearing. Buttar is offering a politics of ends to counter Pelosi’s politics of means, and if his campaign can accomplish anything, it might be to make people think harder about which is the naive approach in an escalating crisis and which is the savvy one.

“I don’t take this stuff lightly,” Buttar says. “My family moved around the world twice to get here…I’ll be damned if I’m going to sit on my hands while a bunch of privileged politicians born with silver spoons in their mouths sully that legacy.”

Unsophisticated and willing. Put that on a yard sign.