Travis Long/The News & Observer/AP; Albin Lohr-Jones/Sipa USA/AP; Diedra Laird/TNS/Zuma

In the old photos, the ones taken right after he was arrested for gunning down three Muslim students in their North Carolina home, Craig Stephen Hicks appears as a dumpy, chinless man with a mousy beard cut too high above the jawline. The style, if you can call it that, looks reasonable from the front but ridiculous from the side. It’s often worn by men who are terrified of being laughed at for letting hair grow on their throat, but who can only ever see of themselves what they find staring back in a mirror.

He looked different at his long-awaited plea and sentencing hearing on Wednesday. More than four years of jail food and life away from the sun had broken down the fat. His spotty, pasty skin hung limp around a baggy orange jumpsuit. The neckbeard he’d once fought so hard to hide now sprouted across his jowls.

When Hicks murdered Deah Barakat, Yusor Abu-Salha, and Razan Abu-Salha, on the frigid evening of February 10, 2015, much of what we are now living through was also under the surface. America’s first black president was still in the White House. The massacre at Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church was four months away. The Nazi rampage through Charlottesville lay more than two years in the future; the mass shooting inside Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue further off than that. Donald Trump would not launch his campaign with a racist tirade about Mexicans, Japanese, Chinese, Muslims, and others until that following summer.

At the time, that is to say, it was still possible for many to pretend—or at least, easier than it is now—that the obvious had not occurred in Chapel Hill. It was possible for police, politicians, and much of the media to look directly at an angry white man who’d barged into a young Muslim neighbor’s apartment and executed everyone inside, including two women in hijab, and see something other than a clear and unmitigated act of Islamophobic terror.

They could see a man who’d amassed an arsenal in his condominium, including an AR-15 that he told police the night of the murders was “loaded up and ready to go,” and see a “sudden, shocking spasm of violence,” in the words of the Washington Post. They could see a man who posted anti-Muslim memes on Facebook and had a record of flashing guns and seething epithets at neighbors of color and repeat, uncritically, his soon-to-be-ex-wife’s assertion that “the incident had nothing to do with religion or the victims’ faith.” They could regurgitate her self-delusion—freshly disproven as forcefully as anything has ever been disproven—that he was merely “a champion of Second Amendment rights” who “believed everyone is equal.” His motive could be cast as a great unknowable.

In a pattern that would repeat itself in the white supremacist massacres to come, tastemakers went looking for anything that could complicate the narrative. Many seized on the fact that Hicks called himself an “anti-theist,” and in addition to anti-Muslim memes had denigrated Christianity and Judaism on his Facebook page. Once he said it would be okay if Obama were Muslim. Another time, he said of all three Abrahamic faiths: “I wish they would exterminate each other!” This proved, the Associated Press said, that he was “a man of contradictions.”

That’s when the Chapel Hill police stepped into the breach. Less than 24 hours after the murders, they announced the erroneous excuse that would spread around the world: that Hicks may have been motivated by “an ongoing dispute over parking.”

Thanks to the evidence produced at the hearing, we now know the truth: That was a lie, based on nothing more than the word of a man who had just walked in off the street and confessed to a triple homicide.

After the murders, Hicks had driven to a nearby lake in a state park, possibly contemplating suicide. (Investigators found a sealed envelope in his car marked “Cops.” It was torn open and had nothing inside.) Then he drove to neighboring Chatham County and turned himself in. His confession was videotaped. Sitting in a 2008 Pittsburgh Steelers conference champions T-shirt, relaxed despite wearing handcuffs and his victims’ blood, he bantered with the officers as if they were meeting over a barbecue.

Hicks seemed eager to win the white authorities’ friendship, apologizing for occasionally having to turn his head because of deafness in his left ear. “I didn’t want you to think I was looking away out of disrespect,” he said. The officer told him not to worry.

The cops seemed comfortable, too. When Hicks started talking about the gun he’d used, the officer asked for details. “I’m a gun guy,” the officer added. They talked for a while about the pros and cons of the Sig Sauer P229 with which Hicks had massacred Razan, Deah, and Yusor. Hicks had bought the gun used. It was a former highway patrol edition—$425, “everything included.” A pretty good price these days, the officer responded, knowingly.

In a bored, resigned tone, Hicks unspooled a version of the myth he’d apparently been telling himself for years: He and his wife had wanted to sell their condo in the Finley Forest community, in a slice of Chapel Hill just over the Durham County line, but got stuck by the recession. Now, he said, their property values were being driven down by “renters” who threw parties and disrespected parking rules. He did not mention that the supposed “renters” who he targeted most violently were almost always people of color.

In fact, Hicks had caused most of his own financial problems, in part by quitting a string of jobs and accruing at least $14,000 in unpaid child support, according to court records. He spent his days playing video games—Assassin’s Creed was his choice on the day of the murders—and posting memes on Facebook. His wife would soon file for divorce.

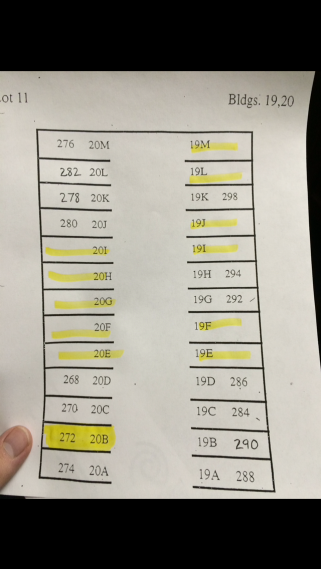

If anything, the neighbors he hated most had probably improved his property values. Barakat’s father, a wealthy Syrian immigrant to Raleigh, had bought his son the condo two years earlier. He and Mohammad Abu-Salha, a Palestinian American psychiatrist and father to Yusor and Razan, had just renovated the condo as a wedding gift for their newly married children. As other neighbors described them, the students were quiet and respectful. The victims’ text messages described Hicks staring menacingly at Yusor in her hijab. At least once he’d flashed his pistol at Barakat. Nonetheless, the young couple hoped to get by without provoking him, even distributing a map among their friends about where they could park without angering the menacing neighbor.

The murdered couple had made a map showing friends where to park, to avoid angering their eventual killer.

Indeed, Hicks admitted to the police that no one had even parked in his reserved spot that day.

Hicks’ most self-serving lies came when he described the 36 seconds in which he committed the murders. He claimed, falsely, that his victims had cursed at him. He speculated, speciously, that Barakat might or might not have come at him with a knife.

Unbeknownst to Hicks, Barakat had answered the door with his cellphone video running, planning to record evidence of harassment. The video was aired to a horrified courtroom packed with friends and family. Hicks banged on the door and said something about too many cars being parked in the lot. Deah tried to respond—nervous and forceful, but polite. There was nothing in his other hand.

Hicks then spoke words that have resonated with white supremacist killers from Reconstruction to Christchurch: “If you’re going to keep disrespecting me,” he said, according to his confession, “I’m going to start disrespecting you.” Before he was even finished speaking, he pulled out his gun like an action hero (one of his favorite films is the white-supremacist fantasy Falling Down) and shot Deah multiple times in the gut. Then he walked into the house. Off camera, the women screamed in terror and pleaded for their lives. According to forensics, Hicks shot Yusor and Razan individually with the barrel of his gun pressed against their foreheads. He then walked back and shot Deah, the dental student, in the mouth. Then he went outside and reloaded.

When Hicks described all this to the police, he mimicked Yusor’s and Razan’s screams. He acknowledged, sheepishly, that he’d probably overreacted.

The idea that police would have thought Hicks’ explanation was worthy of sharing with the public would have been baffling in any other circumstance, especially one in which the roles had been reversed. The police had no investigative reason to announce a potential motive. The only purpose was to influence the international attention surrounding the murders. Moreover, Hicks’ implied motive made no sense: Even if, somehow, there had been an ongoing, mutual beef with Deah and Yusor about anything, and even if that excuse were a plausible excuse for killing somebody, how did it explain Hicks’ decision to execute Razan, a 19-year-old who had never even been to the complex before? Did he need to kill a witness to the crime he was about to confess to? Or was it because she, like her sister, was wearing a Muslim headscarf?

That false conditional—may have been a parking dispute—gave editors a valuable commodity. Because there was never any question about who’d done the killing, and the victims themselves quickly proved to be such resolutely unimpeachable pillars of their community, they needed a mystery motive as a narrative engine. And because that question did not foreclose the possibility that it might have been a hate crime, it even felt journalistically responsible. I shared a byline on one of the most prominent of those “question” stories. I don’t know if the fact that, after weeks more of investigation, I followed it up with a solo effort that dismantled the “parking” narrative makes up for that or not.

For years, media and various officials have allowed white supremacists of all stripes to operate in the space opened up by that false conditional. The man who committed the slaughter at Mother Emanuel in Charleston may have just come from a broken home. Maybe the people who chanted “build the wall!” and cheered Trump when he promised to ban Muslims from America just shared Hicks’ economic anxiety. Maybe if you watched hours of video, or trusted their own diocese, something out there would exonerate the Covington Catholic boys. Maybe Trump knew something that no one else did when he declared that an expressly, emphatically, and uniformly violent white supremacist rally in Charlottesville had included some “very fine people.”

Meanwhile, the racist laws get passed, the camps fill up, and those amassing the arsenals go out and kill again.

I was in the Durham courtroom when the killer pleaded guilty to all counts on Wednesday and was sentenced to three life terms without parole. I’d gotten the last available seat in the packed room: directly behind him, within an arm’s reach of his pallid neck. I could see the entitled annoyance in his shoulders when he complained to the judge about how long the process had taken, how he’d wished he could have just gotten the death penalty and been done with it.

For a long time he’d enjoyed the best thing America has to offer a white man—the presumption of racial innocence—and now part of his punishment was to have it rescinded in public. The trial was “about exposing the hate, bias, and privilege that substituted for the lives of Razan, Yusor, and Deah,” said Satana Deberry, who was elected Durham County district attorney last year. “It was not about parking.”

“What we all know now and what I wish we had said four years ago is that the murders of Deah, Yusor, and Razan were about more than simply a parking dispute,” Chapel Hill’s police chief, Chris Blue, said hours later in an apology. “To the Abu-Salha and Barakat families, we extend our sincere regret that any part of our message all those years ago added to the pain you experienced.”

The apologies were, under the circumstances, what the Abu-Salha and Barakat families had wanted. During the sentencing portion of the hearing, family members took the stand to confront the killer and, it seemed, the nation outside the window. Mohammad Abu-Salha described an atmosphere of rising hate, fueled by blatant hate speech coming from Fox News and the network’s patron in the Oval Office, in which a disappointed white man had been radicalized. “These people with the white gloves do not do the dirty work,” the grieving father said. “They leave that to the feeble-minded.”

“The murders of Deah, Yusor, and Razan did not happen in a vacuum,” said Suzanne Barakat, Deah’s older sister and a physician as well. They happened during an election season in which it had become “not only acceptable but politically advantageous to demonize Muslims” even before Trump had formally entered the race.

Because of my strange positioning behind the killer’s back, I sometimes had the uncomfortable feeling that the witnesses were speaking directly to me. The rows behind us were packed with friends and relatives, American Muslim professionals in business suits and hijab, who’d come despite the horror to watch justice handed down. There were no illusions in that room about the daunting work to be done. Fixing the narrative had to be a part of a larger cure. The deadly false conditional had to be locked away as surely as the killer finally was.

Top image credits: Travis Long/The News & Observer/AP; Albin Lohr-Jones/Sipa USA/AP; Diedra Laird/TNS/Zuma.