Facebook Ad Library; Mother Jones illustration

The federal government has strict disclosure requirements for political ads on television, radio, and print, but the internet remains the wild west for political content. In 2016, campaigns, super-PACs, dark money groups, and Russia were able to purchase ads without disclosing to viewers where they were coming from. So last year, in an attempt to head off scrutiny form Washington, Facebook announced two new policies. First, ads for candidates and political issues would now carry a disclaimer at the top, stating who paid for the ad. Second, clicking on that disclaimer would direct viewers to a new “ad library,” where they could see who else had viewed the ad by state, age, and gender.

But Facebook left a gaping loophole in this system: If a user shares a political ad, the disclaimer disappears for anyone who sees the shared ad, as does the ability to click through it to the ad library. Civil rights and election security experts have warned Facebook that this loophole is ripe for abuse. Several experts on campaign finance expressed surprise when Mother Jones asked them about it, and concern that this loophole could lead to viral, misleading content paid for by undisclosed political actors.

“The public has a right to know who is trying to influence their vote,” says Brendan Fischer, an expert on campaign finance and ethics issues at the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center. “For political actors that want to influence the public without detection, creating posts that are designed to go viral would be an obvious way to do so, and perhaps to do so legally.”

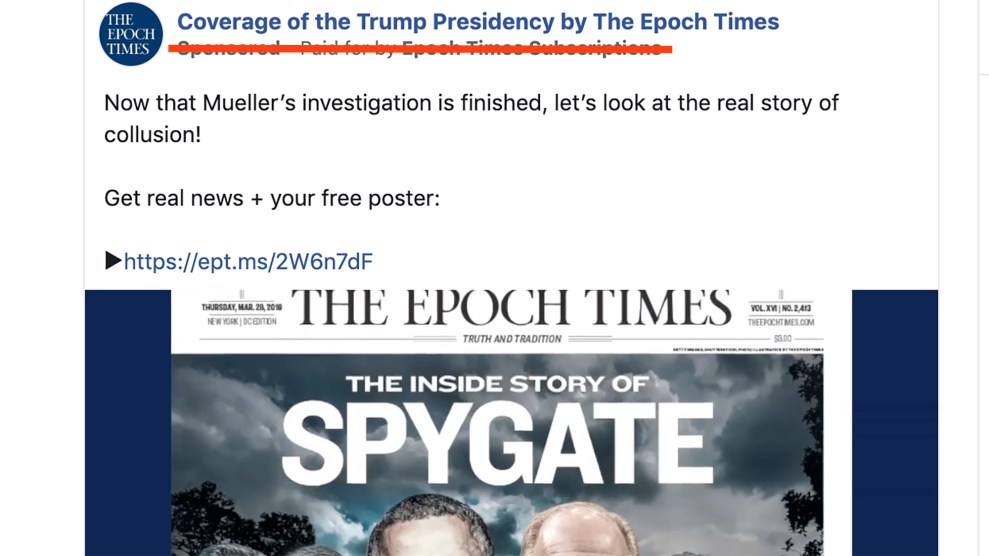

At the top of each ad on Facebook is two lines of text. First, the ad is labeled with the name of entity that paid for it. Below that is the disclaimer line, which states “Sponsored” and then “Paid for by,” followed by the name of the entity. When an ad is shared, the first line continues to be displayed, but the disclaimer line goes away. If the source of the ad is not easily recognizable, such as a candidate’s name, it could be difficult to ascertain where the ad is from, or even that it is an ad at all. The result is that an ad from a candidate’s campaign will still be recognized as campaign-related content, but ads from super-PACs or third-party groups may not clearly come across as ads.

People are likelier to trust information that appears not to be a paid ad but rather content shared by someone in their social circle. “It’s just basic social psychology that we are prone to believe things when we think it is coming from people we trust or who share our interests,” says Bret Schafer, who studies social media and propaganda at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

“So much of what we see on social media is shared by people we know or secondhand connections,” says Ian Vandewalker, an attorney who focuses on campaign finance and voting rights at the Brennan Center for Justice. “Which is one of the ways that things go viral, whether true or false.”

This creates an incentive for political groups and perhaps even hostile nations to design ads that will go viral. Facebook users will see a disclaimer if an ad is displayed in their feed directly from its creator, but the more people share an ad, the likelier it is that a given user will get it via a friend and won’t see the disclaimer. The name of the page behind the ad will still be displayed, but the name could be anything—something generic when it’s actually from an interest group, or something American-sounding when it’s really from abroad. (Facebook has created some certification requirements to ensure that foreign actors are not placing political ads.) Schafer notes that a super-PAC or other outside group could place an ad and then mobilize supporters to spread it as regular content, losing the disclaimer in the process. “It just seems to be a loophole that is there to be easily exploited,” says Schafer.

“It’s a big loophole,” agrees David Brody, an attorney at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law whose expertise covers technology issues. “It seems like it goes more to the priorities of their advertising business model than it does to user welfare.”

It’s one thing to lose a sponsor tag for a product, where the purpose of the ad is still obvious. It’s different when it comes to political content. “It doesn’t matter how it came in front of [a user’s] eyeballs, whether it was a paid promotion or one of their friends shared it or whatever, they’re seeing a piece of content,” says Brody. “And if that content is a political ad, political messaging, they should know that that’s what it is and where it came from and who paid for it.”

Technically, shared ads still live in the ad library, but the library is so difficult to search that even if someone saw content and wanted to ascertain that it was a paid ad, it could be virtually impossible to find it. Brody believes the ad library’s poor search functions are an active choice by Facebook to limit transparency. “That was by design,” he says. “If they wanted to make a good user interface, that was easy to do, they know how to do it.”

A Facebook spokesperson said that the company puts out a weekly report with top ad spenders in order to provide more transparency. The spokesperson also said that by visiting the page of a group or individual, a user could find a link to the group’s ads in the ad library. But if a group is posting many ads—some advertisers post thousands at a time—it’s difficult to find the ad that brought a user down this rabbit hole in the first place.

Facebook announced its first steps toward adding disclosure requirements to political ads in October 2017, soon after a bipartisan group in Congress introduced legislation, the Honest Ads Act, to bring internet ads in line with the rules that already applied to print, television, and radio. (The bill was recently reintroduced but has not come to a vote.) The following February, civil rights advocates warned Facebook about its policy of dropping the disclaimer on shared ads, arguing that it was ripe for abuse by campaigns, super-PACs, and even countries seeking to disseminate political content not easily traced to its source.

When Facebook hired an outside consultant, Laura Murphy, to conduct an audit of the platform’s civil rights impact, civil rights groups raised the issue of the loophole with Murphy, according to one advocate involved in the audit process. The company argues that the disclaimer should tell users only whether they are seeing an ad because someone paid to promote it. When an ad is reposted, its funder is not paying for the ad to be shown to anyone who views it as a result of that share.

But that line of reasoning elides the entire purpose of political ad disclaimers: When people see a political ad, they evaluate it based on where it came from and whether it is an advertisement intended to sway their vote.

During the 2016 election, the Russian government sought to help Donald Trump’s campaign through both paid advertisements and fake accounts that purported to be Americans and sometimes tried to dissuade African Americans and Muslims from voting. The Trump campaign acknowledged to Bloomberg that it sought to persuade African Americans not to support Hillary Clinton through Facebook ads. In 2020, experts believe, the disclosure loophole could be an avenue for super-PACs and dark money groups to spread nefarious messages that few viewers can trace back to the original source.

The Honest Ads Act would create disclosure requirements for online ads. But experts who reviewed that legislation were unsure whether Facebook’s sharing loophole would actually be closed if the bill passes. And nefarious actors, like the Kremlin’s troll farm, may not follow any new rules. Still, Vandewalker says that if there are rules requiring disclaimers, then when content surfaces that doesn’t have one, it will be easier to spot, remove, and investigate.

After proxies for the Kremlin purchased ads in 2016, Facebook added new rules that required all advertisers to register with a US identification card, the last four digits of the administrator’s Social Security number, and a domestic address. But Facebook allows advertisers to write their own disclaimers and does not appear to verify them, meaning that groups could essentially attribute an ad to anyone. Last fall, Vice News placed ads in the names of all 100 US senators that linked back to blank Facebook pages, and Facebook approved them. Advertisers can also create groups with innocuous-sounding names in order to hide the sources behind an ad—a practice common in the oil industry, as uncovered by ProPublica.

Vandewalker says the Facebook loophole encourages political actors to create viral content that essentially becomes free advertising. “It also happens that the ways of doing that—creating outrage and appeals to political tribalism—also seem to be bad for our political culture,” he says, “and increasing extremism and institutional deadlocks that come along with it.”