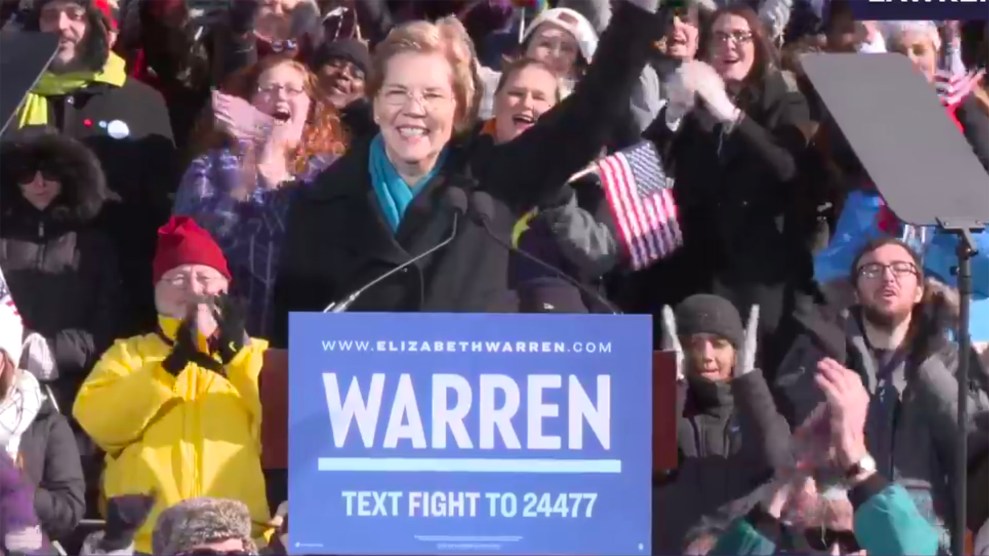

Presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) speaks at an organizing event on February 17 in Las Vegas.John Locher/AP

The early days of the 2020 Democratic primary have been defined by candidates rushing to embrace progressive policy ideas, with a string of candidates throwing their support behind leftist ideas on issues like climate change, tax policy, and health care. On Tuesday, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren added a new category to that leftward shift, releasing a proposal for universal child care, a commitment most of her fellow 2020 hopefuls have not yet made.

Warren’s new plan is a more fully fleshed-out and aggressive plan than what Democrats have proposed in the recent past. Under her proposal, the federal government would administer a network of existing locally run day care facilities for children who would be eligible to attend between birth and the time they start school. No family would pay more than 7 percent of their income for public child care, and families below 200 percent of the federal poverty line would pay nothing at all. According to an economic analysis conducted by Moody’s Analytics and provided by Warren’s office, the deal would give 12 million children access to child care—6.8 million more than currently receive formal child care. The revenue necessary to fund the program, which would cost an estimated $700 billion over 10 years, would come from an “ultra-millionaire tax” Warren has proposed on the richest 0.1 percent of Americans.

“I am so tired of hearing what the richest country on the face of this Earth just can’t afford to do,” Warren told a crowd in Los Angeles on Monday evening as she previewed her plan. “Invest in our babies, invest in our toddlers, invest in our preschoolers—that’s an investment that will pay off for generations to come.”

Child care as a Democratic campaign plank is nothing new. During the 2016 race, both Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton backed universal preschool and advocated affordable child care: Clinton proposed capping a family’s child care expenses at 10 percent of its household income, while Sanders shared Warren’s aspiration for government-backed universal care. But tackling child care has largely languished at the bottom of candidates’ wishlists, lacking either the airtime or details necessary to make it a major campaign issue. Clinton didn’t unveil her child care proposal until May 2016, only two months before the end of the Democratic primary; Sanders, meanwhile, never filled in the specifics on his platform.

Both the scope and timing of Warren’s proposal set her apart from her 2016 predecessors—and the rest of the 2020 field. “This is the first time we’ve seen someone coming out of the gate with a child care plan,” says Katie Hamm, the vice president of early childhood policy at the Center for American Progress Action Fund, the advocacy wing of the liberal think tank that provides policy advice to elected officials. CAP gave feedback to Warren’s staff on her proposal.

There’s been a struggle to get lawmakers to line up behind a universal plan. The most recent Democratic legislative effort, spearheaded by Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) in September 2017, similarly focused on access to quality child care and capped what families would pay, but higher-income families would not be eligible to participate. The last president to gain traction on the idea was Richard Nixon, whose White House worked with congressional Democrats to craft a proposal that, like Warren’s, would have established a national network of federally funded child care centers and subsidize costs based on family income. The bill passed both chambers of Congress, but Nixon ultimately vetoed the measure because of concerns about the “family-weakening” implications that “communal” approaches to child-rearing might have. (Nixon aide Pat Buchanan put it more bluntly, suggesting the policy would lead to the “Sovietization of American children.”)

The characterization stymied future efforts, though it’s not one most 2020 Democrats worry about—especially in a campaign largely defined by candidates’ willingness to move to the left on economic issues. In fact, economic gains played a prominent role in Warren’s unveiling, as she drew attention to how federal investment in the issue could be a big boost to child care workers, working parents, and the economy at large. “More than a million child-care workers will get higher wages and more money to spend,” Warren said in a blog post accompanying the release. “More parents can work more hours if they choose to, producing stronger economic growth.”

Indeed, the child care industry has its hand in economic stagnation: A CAP analysis of data from the National Survey of Children’s Health found that nearly 2 million parents of children under five left, turned down, or changed jobs to address a child care conflict. (Child care costs more than in-state tuition for public universities in many states.) Meanwhile, the median hourly wage of a child care worker, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is $10.72—just a hair above the federal minimum wage.

That emphasis also distinguishes Warren’s proposal from past child care pushes, Hamm says, which have often focused more on the benefits to children and the families seeking support. “It’s something that’s often been described as family policy, but we have growing evidence that child care is an economic necessity,” Hamm explains. “It not only addresses family economic security, but it also contributes to macroeconomic growth.”

For Warren, elevating the issue is personal. In her blog post, the senator described the struggle she faced balancing her full-time job as a law professor with raising two little kids as a single mother. When babysitters and day care centers failed her, she contemplated quitting her job until her 78-year-old aunt moved in to take care of the kids. “Not everyone is lucky enough to have an Aunt Bee of their own,” she writes.

And for other candidates, the issue has been personal too. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, a mother of two children, has been a vocal proponent of affordable child care since she was first elected to federal office more than a decade ago. Sen. Kamala Harris, a stepmother to two, talked about the need for affordable child care in her opening pitch to voters when she announced her candidacy in Oakland last month. But while these candidates and others have joined Warren on the left of some economic concerns, child care isn’t yet one of them. Harris and Gillibrand have stated support of universal preschool, but have not proposed policy as sweeping as Warren’s. Sanders, who officially entered the 2020 fray Tuesday, vowed to go as far as Warren, but has not put forward a proposal.

But just as faint cries for a public option turned into broad support for Medicare-for-all, there’s a chance Warren’s early move could force the hand of others, turning child care into a 2020 progressive litmus test, too. “A lot of issues have been discussed early on in the campaign, and it will be really important if all candidates talk about child care early on, too,” Helen Blank, the director of child care and early learning at the National Women’s Law Center, tells Mother Jones. “We’ll no doubt see many proposals as candidates make a commitment to this issue.”