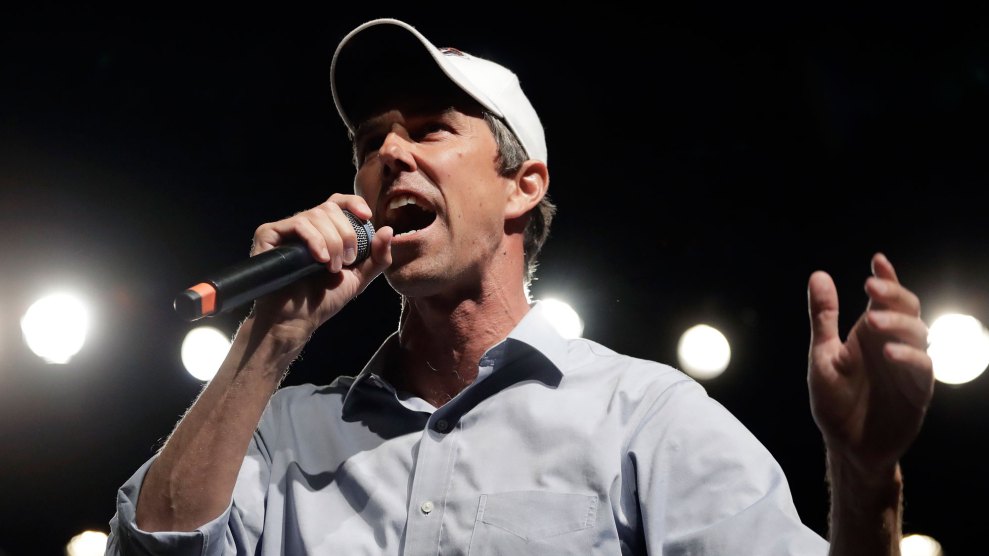

Eric Gay/Associated Press

On Monday night, a few hours before President Donald Trump’s reelection rally in El Paso, Texas, former Democratic Rep. Beto O’Rourke and a group of allies—including Rep. Veronica Escobar and the Border Network for Human Rights—will lead a march to promote, as O’Rourke put it, “a bold, confident, ambitious message for the country from the U.S.–Mexico border.” The march will end with an address from O’Rourke in a park across the street from the arena from where Trump is set to speak, but it’s the starting point that carries perhaps the most symbolic significance: Bowie High School.

Bowie is the beating heart of the historic Mexican American neighborhoods of south El Paso, but it’s more than that. It was also pivotal to the development of modern border security.

Bowie High is situated a few hundred yards from the Rio Grande in a part of El Paso known as the Chamizal—the last piece of Mexican territory ceded to the United States in 1964. (The neighborhood had ended up on the north side of the Rio Grande after the river changed course, and it took years for the two nations to negotiate a compromise and construct a permanent channel.)

Owing to its location—it was separated only by a patchy chain-link fence from the international boundary—large numbers of unauthorized migrants would cross Bowie’s property on a weekly basis, and Border Patrol agents would drive across the campus in pursuit. But the Border Patrol did more than that. Agents staked out the campus and targeted students and teachers, too. In an interview with the El Paso Times in 1992, Bowie High School principal Paul Strelzin recounted a series of horror stories from faculty.

There was the secretary who was followed to her home by Border Patrol agents who demanded to search her car. There was the assistant football coach who was giving a few players a ride only to be pulled over by Border Patrol; an agent put a gun to his head until other coaches were able to vouch for his citizenship. Strelzin complained to the paper that Border Patrol cars would park in the faculty parking lot at Bowie and harass students before and after school; sometimes they’d sit and watch marching band practice.

Simply going to school meant putting up with a potentially life-threatening climate of racial profiling; at the very least it meant being subjected to questioning from Border Patrol agents. (“Why shouldn’t you students answer agents’ questions?” Dale Musegades, the El Paso Border Patrol sector chief, complained to students who confronted him. “Is it a deliberate attempt to antagonize the Border Patrol? All you have to do is answer their questions.”) So later in 1992, Bowie fought back. Five students, along with the secretary and the assistant coach, filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging that the Border Patrol was infringing on their civil rights. A federal judge agreed, granting an injunction in December 1992 that ordered the Border Patrol to stop harassing Bowie High students and faculty unless there was a “reasonable suspicion based on specific articulable facts.”

The story doesn’t end there. Under pressure, the Border Patrol established a community review board to handle complaints, and shortly thereafter a new chief took over the El Paso sector—a 48-year-old career officer named Silvestre Reyes.

Rather than chasing migrants through a high school parking lot and harassing kids, Reyes offered a new strategy dubbed “Operation Hold the Line.” It basically amounted to an overwhelming show of force along the border in El Paso, making it physically impossible for individuals to cross. It drew protests in both El Paso and Juarez, but it worked. Illegal crossings in El Paso dropped dramatically in the immediate aftermath, and Reyes’ strategy soon became the Border Patrol’s de facto national strategy, replicated in San Diego and other urban areas. Reyes, for his part, was elected to Congress from the state’s 16th District in 1996 and served eight terms until he lost in 2012 in a Democratic primary to…Beto O’Rourke.

The creation of modern Border Patrol policy isn’t a feel-good story. A major consequence of the blockade approach to urban border security, of which Bush-era fencing was the natural evolution, is that migrant routes were pushed into more wide-open spaces, such as southern Arizona, where thousands of migrants have died in the desert in the decades since.

But there’s a lesson in the legal fight at Bowie that has parallels to the current moment, as Trump pitches an unpopular wall in a border city that doesn’t want him, on a border he has routinely smeared as a haven of crime. The Border Patrol’s outrages at Bowie were fundamentally an outgrowth of the idea that some Americans’ security mattered more than others—that trampling the rights and wishes of Americans in one community was an acceptable price for securing the peace of mind of Americans in another. El Pasoans fought back. And then, as now, it started at Bowie.