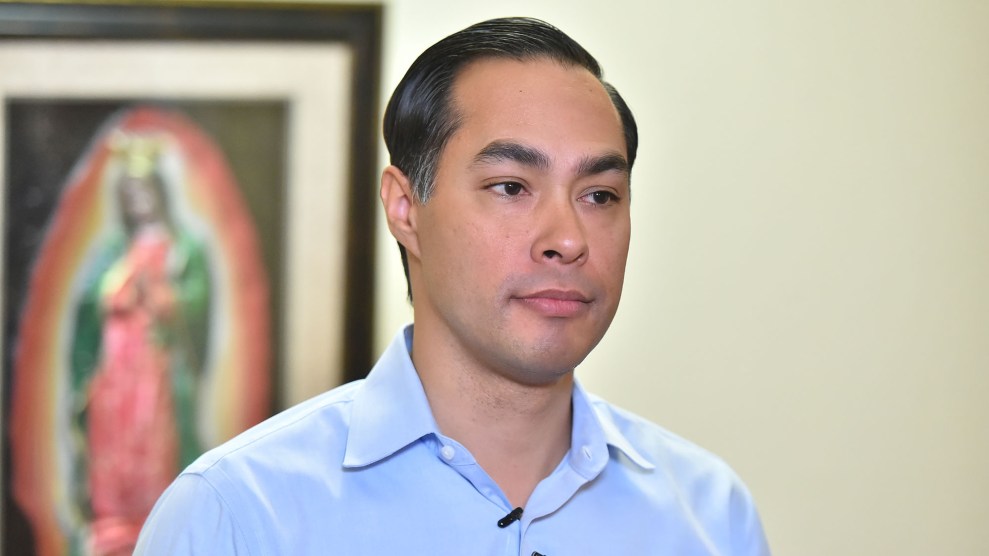

Robin Jerstad/ZUMA

When Julián Castro decided nearly a month ago that he would launch his presidential campaign on January 12, he couldn’t have imagined such a fortuitous backdrop to his kickoff. With the government shutdown entering its fourth week, President Donald Trump has amped up his anti-immigration rhetoric in an effort to build an unpopular wall along the Mexican border. Democrats finally feel they have the upper hand on immigration issues, and onto the scene steps Castro, the highest-profile Latino ever to seek the Democratic presidential nomination.

Castro’s Saturday announcement in San Antonio, where he served as mayor from 2009 to 2014, comes four days after Trump attacked undocumented immigrants as murderers and criminals in an address from the Oval Office and two days after Trump traveled to the border city of McAllen, Texas, 200 miles south of Castro’s hometown, to gin up fears of a crisis at the border.

Even a few years ago, Texas residency imposed a ceiling on Democratic politicians aspiring to higher office. The traditional stepping stones to the presidency—the Senate and a governorship—were seemingly off-limits to Democrats in the deep-red state. No longer. The Southwest is increasingly the party’s future, after growing Hispanic and minority populations helped Democrats win a Senate seat in Arizona in November and nearly capture one in Texas. Democrats will be desperate to organize and energize Latino voters in 2020, and that could boost Castro’s appeal as the party’s only serious Latino candidate in what promises to be a crowded field.

On the other hand, that crowded field may pose an insurmountable challenge. Castro lacks the name recognition of some of his more prominent rivals, and there’s no evidence that Latinos will embrace Castro simply because he’s Latino.

But if there’s anything helping Castro now, it may be Trump and his insistence on putting immigration at the center of the agenda.

Trump’s border wall is “a broad brush against Latinos, even though he tries to make it about illegal immigration,” says James Aldrete, a Democratic consultant in Austin. Castro’s own biography, by contrast, is the aspirational story Latinos hope for. “His story really is our story. And the fact that it will get told in a positive way that we can take pride in, in this moment especially, is huge.”

Castro and his twin brother, Rep. Joaquín Castro (D-Texas), were raised by their grandmother and their mother, Rosie Castro, a community organizer and local leader of a Chicano political party who made rallies and progressive organizing a formative part of their youth. They both attended Stanford University and Harvard Law School before returning to San Antonio to enter politics. At 26, Julián became the youngest member of the city council in history. He went on to a successful mayoralty, then joined the Obama administration in 2014 as the secretary of housing and urban development. Joaquín became a state representative before being elected to Congress in 2012.

Since leaving the Obama administration, Castro has laid the groundwork for a presidential run. He launched a political action committee, raising nearly $500,000 (but declining to take money from corporations) during the 2018 cycle, and doling most of it out to Democratic candidates at the local, state, and federal levels, including to politicians in key primary states like Nevada and Iowa. He also hit the campaign trail for Democrats, including Stacey Abrams in Georgia, raising his own profile while doing favors for people whose endorsement would be important in a crowded Democratic primary. This work was savvy, but also a necessity. Castro passed on two potential campaigns in 2018: for Senate, when Rep. Beto O’Rourke stepped up to run, and for Texas governor. Without either seat, Castro lacks the platform of a sitting national or statewide politician, and so he has had to build one of his own.

Despite the current spotlight on immigration, it has not always been central to Castro’s political career. In municipal politics, Castro worked to bring together the city’s Latino majority and its Anglo north side, as well as the business community. Public-private partnerships helped fuel the city’s growth. His biggest achievement, expanding pre-kindergarten education, was a successful exercise in this coalition building. To fund it, he convinced two of the city’s most prominent businessmen to support a $30 million sales tax.

Castro has previewed a broader progressive message on the campaign trail that does not focus on immigration. In Iowa this month, he told voters his policy agenda will include universal health care and a solution to soaring housing costs. He has also endorsed a Green New Deal and a proposal to raise the marginal tax rate for the richest Americans. But the current political moment will make immigration unavoidable for Castro, says Aldrete. “The larger debate with Julián and a number of other candidates is who are we as a nation,” he says. “I think his biography will speak to that.”

Castro appears to have intuited this. Immigration is a subtext of his overarching message about preserving the American dream for everyone. His recent memoir, An Unlikely Journey: Waking Up from My American Dream, begins with the Trump administration’s family separation policy and his own grandmother’s journey across the border as an orphan in 1922.

So far, Castro is barely registering in early polls of Democratic primary voters. Likely candidates with higher national name recognition are on top, including former Vice President Joe Biden, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, and O’Rourke of Texas. In a field that could expand to as many as two dozen candidates, the challenge for Castro will be to find a way to stand out.

Latino voters could be key to his success or failure. They represent a growing part of the Democratic electorate—but also one that turns out to vote in lower numbers. The Hispanic population skews younger than the overall population, and young voters in general are harder to mobilize. A November poll by Latino Decisions found that a higher share of Latinos had a favorable opinion of Biden, Sanders, and Warren than of Castro. But the survey also found that if Democrats nominate the first-ever Latino candidate for president or vice president, 67 percent of Latinos will be more likely to vote for the Democratic ticket. “As he gets more known, I think he will have a tremendous upside,” says Matt Barreto, a political scientist at the University of California-Los Angeles and the co-founder of Latino Decisions. “But he’s going to have the challenge of just cutting through some of the other big names that might be in the field this year.”

“Latino voters are not going to only vote for one candidate because he’s of his or her ethnic background,” says Jeronimo Cortina, a political scientist at the University of Houston. “You have to have the right policy issues and you have to have the right policy solutions for the issues that Latinos care about.”

If Castro is successful in energizing Latino voters, the 2020 primary calendar could help him. Latino influence in Democratic presidential primaries has historically not matched their importance to the party’s overall fortunes because early primary states like Iowa and New Hampshire have low Latino populations. But this year, Latinos will have a bigger voice because California, which has more Latinos than any other state, leapfrogged up the political calendar, from June to Super Tuesday on March 3. Moreover, California’s four weeks of early voting will mean absentee ballot counting will begin on February 3, the same day as Iowa’s first-in-the-nation caucuses. Texas, home to the second-largest Latino population, will also vote on Super Tuesday, but early voting will begin in February.

Of course, in both states, Castro may be battling other big names: Sen. Kamala Harris of California, who’s expected to announce her candidacy in the coming weeks, and O’Rourke in Castro’s home state, who is also contemplating a run.

The fact that Castro will be the first major Democratic Hispanic candidate for president could free him from the pressures and stereotypes that may trouble other potentially historic candidates, like women running in the shadow of Hillary Clinton’s failed campaign. “There’s all the idiotic questions about if so-and-so is likable enough,” says Jason Stanford, a political consultant in Austin. “That’s that prism we see that through. All the black candidates we see through Obama’s prism. Can we have another black candidate so soon?” But Castro is following no one. Bill Richardson, a Latino ex-governor of New Mexico, mounted a campaign in 2008, but it fizzled quickly. “We don’t have that national political framework for a Hispanic candidate. He’s not compared to anyone. Is he another…what?”