Every Sunday, Scott Lloyd attends St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church in Front Royal, Virginia. Founded in honor of a fallen Confederate soldier, the red-brick building sits on Main Street in this picturesque town of 15,000 at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains and is the heart of its vibrant and devout Catholic community. Twice a week, the parish hosts a Tridentine Mass in Latin, a relic of Catholicism’s pre-1965 Vatican II order that is now eschewed by most contemporary churches. Lloyd, 39, lives on the outskirts of town in a two-story colonial with his wife, Ann—his college sweetheart—and their seven kids. That puts them in line with St. John’s congregation, whose 1,200 families, a congregant once wrote, have an average of six children each and have gone 15 years without a teen pregnancy.

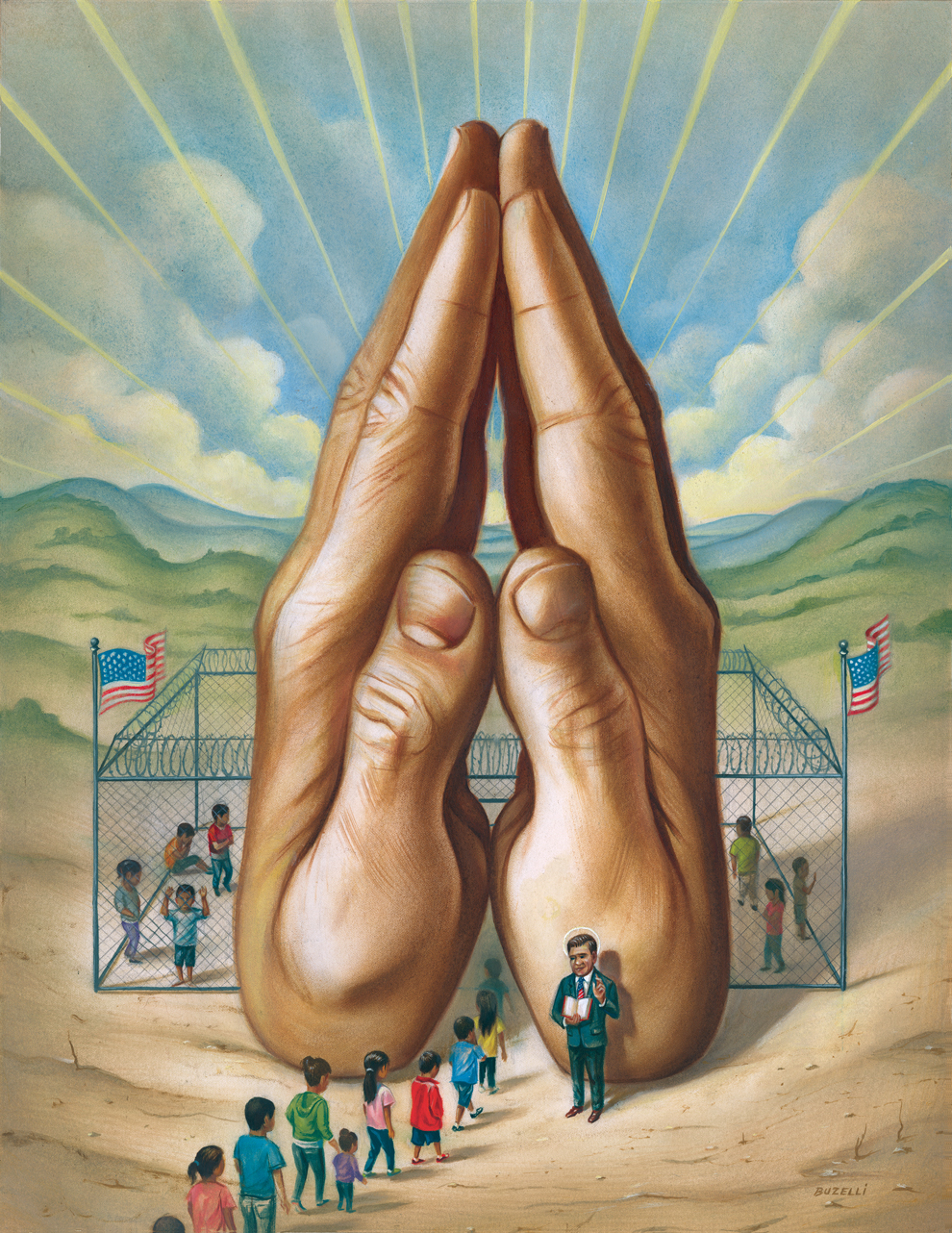

For more than a year and a half, Lloyd has been commuting 70 miles to Washington, DC, where he serves in the Trump administration’s Department of Health and Human Services. For the last 20 months, Lloyd has been charged with running the department’s Office of Refugee Resettlement, a small agency charged with helping refugees arriving in America. It also runs shelters housing detained child migrants, including some 3,000 children seized from their parents at the border in the spring of 2018. Last month, it was revealed that Lloyd’s bungled handling of the reunification of these kids with their families was under formal HHS review; as of this writing, 171 children are still separated from their families. Today, the department announced that Lloyd will be leaving the refugee office for a new role involving outreach to religious communities with HHS’s Center for Faith and Opportunity Initiatives.

Lloyd’s tenure at ORR was controversial. When he was appointed to run the agency, Lloyd had little prior experience with refugees but a long history of working to restrict reproductive rights. Under both the Bush and Obama administrations, the agency routinely permitted undocumented teens to get abortions if they obtained private funding. But after March 2017, when President Donald Trump put Lloyd in charge of the agency, he instructed ORR shelters to send pregnant young women to have consultations at religiously affiliated crisis pregnancy centers that oppose abortion and to undergo medically unnecessary ultrasounds. Once, Lloyd ordered a shelter to halt a young woman’s two-step medication abortion halfway through while he conferred with colleagues about deploying a scientifically unproven method to “reverse” the abortion to “save the life of the baby.” (After Lloyd had the girl taken to an emergency room to check on the “health status” of the fetus, she was eventually allowed to complete the procedure.) In another case, he ordered that a pregnant girl who was otherwise ready for release should be held in custody until she received anti-abortion counseling. In yet another, he denied an abortion to a pregnant rape survivor who had threatened to hurt herself if forced to carry to term, until a federal judge intervened. He went so far as to personally travel to visit one young woman in ORR custody to try to dissuade her from having an abortion—he delivered a similar message to another young woman by phone. In a 2017 deposition, Lloyd acknowledged he had never approved an abortion request that crossed his desk. This fall, Politico revealed that Lloyd is writing an anti-abortion book while in office based on his own spiritual “awakening.”

To understand Lloyd’s actions, it helps to consider his personal experience. In 2004 he wrote a law school essay describing his guilt and outrage after a young woman he slept with got pregnant and chose to have an abortion. “The truth about abortion is that my first child is dead, and no woman, man, Supreme Court, or government—nobody—has the right to tell me that she doesn’t belong here,” Lloyd wrote in the seven-page essay, which I first revealed in an August Mother Jones story.

It also helps to look at the Catholic community of Front Royal, where he has chosen to raise his family. Since 1979, when Christendom College (mascot: Crusaders) set up shop there, the town has attracted an array of conservative institutions linked to the church. There’s Seton Home Study School, a leading provider of Catholic home-schooling curricula. And Human Life International (HLI), which boasts of being the world’s largest international pro-life advocacy group, one of a variety of organizations that advocate preservation of the “natural family.”

“You know how people play the Kevin Bacon game?” explains Stuart Nolan, a former law partner of Lloyd’s who is chairman of the HLI board and a parishioner at St. John the Baptist. “If you went through six degrees of separation, you’d probably find that a lot of the folks have some connection historically to one of those three organizations—a lot of the Catholics you run into in town used to work for Human Life International or Seton, or they still do, or they went to Christendom, or they were just visiting because their oldest child went to Christendom and they fell in love with the community and then relocated here. It continues to happen, and the community continues to grow.”

This community’s great hope is to redefine what American families should look like, and Lloyd is their tribune in Washington. His new job, where he’ll be working alongside other pro-life appointees to further the department’s agenda, could present further opportunities.

“When you’re as bad at your job as the reports have said Scott Lloyd was at his, you don’t get a cushy reassignment. You generally get fired,” says Mary Alice Carter, director of Equity Forward, a pro-choice group that keeps a close eye on HHS. “He had an agenda while he was at the Office of Refugee Resettlement that didn’t really fit the job, and now he’s getting a chance to put that agenda into play at a place where he will have full range to do so.”

For a Trump political appointee, Lloyd stands out as shy and spotlight-averse. In October 2017, during a tense congressional oversight hearing on refugee admissions, he gave terse answers as he shuffled in his chair and fiddled with his pen. He has declined most interview requests, including Mother Jones’. “The noise that might be generated over one case or another can be a distraction,” Lloyd told the Catholic network EWTN. “I think it’s best to just keep your head down and keep doing the work.”

That determined, unobtrusive approach is one he’s had since youth. Lloyd grew up in the affluent town of Stone Harbor, New Jersey, before heading off to James Madison University in 1996 to major in English. The summer after graduation, he interned at his local paper, the Cape May County Herald. His editor, Jim Vanore, says Lloyd was “a very serious, very quiet kid” who worked harder than many interns and once even set off the burglar alarm after the paper’s bookkeeper had left for the day, certain the office was empty. “She said, ‘Jim, the kid is so quiet I didn’t know anyone else was in the building,’” Vanore recalled.

When Lloyd was a 25-year-old law student at the Catholic University of America, he shared the essay about his partner’s abortion with classmates during an ethics seminar. His essay recounted how he had begged her to choose adoption, but in the end drove her to the clinic and gave her cash—mostly $1 bills—to pay for half the cost of the procedure, and then reluctantly took a seat in the waiting room.

The experience shook him. For months afterward, Lloyd recalled drinking so heavily that he would find himself passed out on park benches and in elevators. Once, he got hauled into court on charges of disorderly intoxication. He sought counseling from a minister who told him that no sin was unforgivable and asked him to read the Bible and think about God as penance. All this anguish cemented his staunch belief that abortion is wrong in all circumstances. “Our entire society needs to recognize these truths,” he concluded, “and support them with our efforts, laws, and the true application of justice.”

“The Jews who died in the Holocaust had a chance to laugh, play, sing, dance, learn, and love each other. The victims of abortion do not,” Lloyd wrote. While Roe v. Wade enshrined a right to privacy and bodily integrity, Lloyd wrote that he “would argue that a woman, when engaging in consensual sex, gives up the right to both.” (In the essay, Lloyd made clear he opposes abortion even in instances of rape or incest or to save the mother’s life.) Abortion should be illegal, he reasoned, due to the bodily sacrifice of biblical figures. “The martyrs that built our church sacrificed their bodies to the most violent, tortuous treatment. All our Church requires is that a woman has the child growing inside of her,” he wrote.“To some this is just gibberish, even to some Catholics. To me it is far more real than anything else on this mortal earth.”

Lloyd spent law school immersed in pro-life advocacy. He helped Robert Destro, his constitutional law professor, represent Terri Schiavo’s family in their 2004 case to keep their daughter on life support against her husband’s wishes. (In June, Trump nominated Destro to lead the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor; he has not been confirmed by Congress as of this writing.) Lloyd also became president of the campus Advocates for Life group. In the winter of his second year, he and two law school friends decided one night over beers to start a new project named “Americans on Call,” a nationwide movement of anti-abortion ambassadors on standby to help women get the support they need to have babies. “It is not the job of the legislatures or the Supreme Court to end abortion through laws or litigation. It is in the people’s hands to end it through action,” the three friends wrote. “When you pray this year, pray that you will have the opportunity to bring a pregnant woman to the help she needs to bring her child to term.”

After law school, Lloyd shifted away from his efforts to end abortion through supporting pregnant women, instead taking a job to change the law to restrict access to the procedure. He joined George W. Bush’s Department of Health and Human Services, where he helped craft “conscience” regulations that allowed providers to refrain from administering medical care, including for abortion and contraception, that they objected to. (Barack Obama overturned portions of the regulations, but the Trump administration fully reinstated them in January 2018 after bringing Lloyd and two other Bush-era lawyers who wrote the rules back to HHS.)

Lloyd’s path “sounds very similar to the kinds of stories I have heard from lots of [pro-life] activists,” says Ziad Munson, a sociology professor at Lehigh University who interviewed hundreds of anti-abortion advocates while researching his book The Making of Pro-Life Activists. “They tell themselves stories about incidents in their life related to a pregnancy or birth,” he says. “They’re an important part of their activist identity.”

“The thing is, activists don’t think that they’re right. They know that they’re right,” Munson says. “They don’t perceive it as pursuing their own beliefs. They see it as doing what’s right for society.”

After Obama’s 2009 inauguration, Lloyd left government to join a small Washington-area firm run by Nolan, a fellow CUA law alum and another protégé of Destro. Over the next two years, Lloyd and Nolan teamed up on a number of projects mixing religious and professional pursuits, including representing Catholic broadcasters seeking station licenses. Both moved their families to Front Royal around 2010, co-founding a new pro-life “legal apostolate”—part law firm, part ministry—aimed at furthering the church’s values. They opened their doors on March 25 that year to coincide with the Feast of the Annunciation, when Catholics celebrate the day the Virgin Mary learned she would conceive Christ. “Let’s be blunt. The law is pagan territory. It is, in fact, one of the least Christian elements of our society,” Lloyd explained in a speech celebrating the firm and its potential to transform laws on gay marriage, divorce, and abortion. “A bold statement, I know,” he concluded, before suggesting his firm was like the “unmarried peasant girl” who gave birth to Jesus.

Lloyd and Nolan set up their office at 4 Family Life Lane, an address that is part of a $7 million, 85-acre complex owned by Human Life International and currently or formerly home to four religious advocacy groups, two Catholic schools, and two publishers of abstinence awareness and chastity materials. They’re joined by an online Christian retailer, a Catholic scouting program, a pro-life investment firm, and a pro-life media outlet. Until 2016, Lloyd served on the board of a Front Royal crisis pregnancy center with ties to St. John the Baptist and run by one of its parishioners: the wife of HLI’s education director. In 2010 and 2011, his writing was published on blogs run by two groups inside HLI’s compound and by HLI’s American affiliate, and he has served on the boards of several organizations based in the compound.

Some of the groups inside also have deep ties to the right-wing political elite: Ken Cuccinelli, a former Virginia attorney general and 2013 GOP gubernatorial nominee, is on the board of a Catholic school located in the compound, along with conservative columnist L. Brent Bozell III and Alfred Regnery, of the conservative publishing empire. Federalist Society Executive Vice President Leonard Leo, a key adviser to Trump on judicial nominations, also sits on the board of a Catholic teaching corporation that was housed within HLI until 2017.

HLI was founded in Maryland in 1981 by the Reverend Paul Marx, a Benedictine monk who left Minnesota after his pro-life advocacy came under fire. (He’d displayed a jarred fetus during a lecture to schoolchildren and blamed Jews for a global tide of abortions.) He moved HLI to Front Royal in 1996, spending $6 million, much of it raised from devout Catholics, to outfit a new headquarters. Under Marx’s leadership in the ’80s and ’90s, HLI worked with a handful of anti-abortion activists who advocated bombing abortion clinics and murdering providers. HLI also developed graphic mailings, including one flyer featuring a fetus’ severed head; 9,000 copies were sent to residents of central Connecticut.

Today, HLI members call themselves “pro-life missionaries to the world.” With offices in Rome and Miami, between 2006 and 2016 they gave at least $12 million—about a third of the group’s total revenue—to pro-life causes in dozens of countries, supporting everything from El Salvador’s total abortion ban to training for activists fighting the Philippines’ law providing free contraceptives.

In 2014, a pagan priestess offered tarot readings at the downtown market in Front Royal. When some of the town’s conservative Christian residents threatened to boycott the business where she’d set up shop, the owner asked her to leave. Then the priestess unearthed a decades-old town law banning fortune-telling and “magic arts,” posting about the ordeal on Facebook. Soon, the town council held two packed meetings to debate repealing the law. As cross-bearing protesters marched outside, Front Royal’s Christians flooded the mic to defend the ban, warning that repeal could usher in a faith war, crime, paganism, Satanism, and homosexuality. Some worried about the “abomination” of giving the fortune-telling power of God to mere mortals. During his two turns at the mic, Lloyd flexed his legal training, arguing the ban did not violate the freedoms of speech and religion. Nolan submitted a list of legal citations. One council member responded that he felt like he was in the movie Footloose: “Kids wanted to dance, and the state said they couldn’t. And here we are…saying, ‘Please impose our moral viewpoint on everyone else.’” Ultimately, Front Royal’s Catholics lost the battle. The town council repealed the ban, despite opposing votes from two devout council members who have since won higher elected office in the county.

Within a couple of months of Trump’s inauguration, new appointees at the Department of Health and Human Services asked Lloyd if he wanted to be the refugee office’s deputy. He said he’d prefer to be the director. Already working on the HHS transition team, Lloyd had submitted a résumé citing his experience as a lawyer for the Knights of Columbus, a pro-life Catholic fraternal organization where he spent a year crafting a report advocating State Department protections for persecuted Yazidi and Christian communities in the Middle East. While Lloyd had far less experience working with refugees than many of his predecessors did—Obama’s ORR head, Robert Carey, had spent 15 years as a vice president at the International Rescue Committee—he was nonetheless installed at HHS in February 2017, where he started to make big decisions before he officially became director.

While still formally a special adviser to Trump’s HHS transition team, he helped craft a policy change that required teens in ORR custody, many of whom faced a high risk of rape and sexual assault during perilous journeys to the United States, to get the director’s approval before terminating a pregnancy. In early March, Lloyd, still not yet the ORR director, sent a stern note chiding staffers for allowing two abortions without the ORR central office’s explicit approval. He instructed a shelter holding a young woman who had obtained a court order allowing her to receive an abortion without parental consent to ignore it. A week later, on a trip to San Antonio, he spoke with two other girls at an ORR shelter. He emailed the staff after the visit: A pregnant girl missed her native Honduran food, he said—could they find a way to get her bananas and soup, and also a more comfortable mattress? The other girl had just had an abortion: “Please have her clinician keep a close eye on her,” Lloyd wrote. “As I’ve said, often these girls start to regret abortion, and if this comes up, we need to connect her with resources for psychological and/or religious counseling.”

While Lloyd’s persistent personal attention to abortion is directed at the tiny portion of pregnant migrants in his care, he’s also taken broader actions aligning himself with the administration’s hardline immigration stances. On the afternoon of March 24, 2017, his first official day as ORR director, Lloyd sent out an email. He had recently read news reports about two DC-area cases in which immigrant kids allegedly committed crimes. While charges were dropped in one of the cases, he later said in a deposition that the reports had made him worried about gang activity and violence by the children in his care after they were released. At 1:24 p.m., Lloyd sent a note out to ORR’s staff: “RE: New Secure and Staff-Secure Release Procedure.” Local staffers, he ordered, “may not approve a release” of a child who had ever been held in the agency’s strictest facilities “until they receive notification” that he personally had signed off. With a few keystrokes and minimal research, Lloyd had added a layer of control over hundreds of immigrant kids.

In Lloyd’s new role, his orders and interventions on abortion only grew bolder. “The unborn child is a child [in] our care,” he wrote in another staff email related to a girl who’d requested an abortion. The Arizona shelter holding her should send her to a Christian anti-abortion clinic he’d identified in Phoenix for an ultrasound and “options counseling,” he wrote. Under no circumstances, added Lloyd, should the girl meet with an attorney about abortion rights.

Under Lloyd’s watch, administration lawyers defending ORR have declined to say whether migrant minors in HHS facilities have a constitutional right to due process; one judge called this position “remarkable.” In the last year, three federal courts have rebuked Lloyd for making decisions based on his personal beliefs—what one judge called his “flight of whimsy.” The New York Civil Liberties Union sued Lloyd over his hastily created secure release policy after it kept one teen with no criminal record or gang affiliation separated from his mother for seven months.

When an NYCLU lawyer asked Lloyd what he’d done to prepare for his deposition in the case, he replied that he’d spoken with his attorneys and “thought and prayed.” He then confirmed that beyond reading “news reports” and speaking briefly with two colleagues, he’d done no research before assigning himself unilateral power to keep kids locked up.

Ruling against ORR, the judge, a Bush appointee, admonished Lloyd for keeping kids “hostage” based only on personal preference and cited NYCLU research showing more than 700 teens had been held an average of six extra months because of the policy. “So far as I can gather, there was no process at all here,” the judge said. “I don’t understand how you could possibly justify what happened.”

“He’s drawing on his personal views in terms of how he makes decisions, and it just seems to be completely untethered to any rational conceptualization of the child welfare values that should be animating how this agency is operating,” says NYCLU lawyer Paige Austin, who argues that Lloyd has taken “a very personal level of intervention in people’s lives, and he’s basically just making it up.”

For all the outrage Lloyd caused in pro-choice circles, he and his office were all but unknown to the public until April, when the administration began implementing a “zero tolerance” border policy, transferring all adults entering the country illegally to the Justice Department for prosecution while putting their minor children into ORR custody.

About two weeks before the first press reports on widespread family separation appeared, several pro-life nonprofits, including Front Royal’s Human Life International and C-Fam, a conservative think tank designated as an anti-LGBT hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, hosted Lloyd at a UN roundtable on “the effect of urbanization and migration on the family.” While Lloyd acknowledged his agency’s mandate to ensure the “human dignity” of migrants, he said ORR’s booming expenses threatened “the dignity of the American taxpayers.” He floated a plan to curb ORR’s population by taking in only kids who could demonstrate they were escaping family abuse or had “legitimate” claims to asylum, and turning away those fleeing economic hardship. He did not reveal that the number of kids in ORR’s taxpayer-funded care was climbing not because of a flood of economic migrants, but because of a program that had secretly already separated more than 700 kids, some younger than four, from their relatives.

Later that week, Lloyd signed an agreement giving other federal immigration agencies unprecedented access to ORR data, including, crucially, the immigration status of a minor’s potential sponsors—adults already in the United States who are willing to care for the child after release by ORR. Immigration advocates argued the move would put future caretakers at risk of deportation and discourage potential sponsors from coming forward. In September, a senior immigration enforcement official told Congress the agreement had helped his agency arrest dozens of potential sponsors.

When family separations finally came to light and national outrage exploded, Lloyd kept mum as his agency made one move after another exacerbating the crisis. The office struggled to differentiate children taken from their parents or guardians from those who’d come into the country unaccompanied, so in response to a July court order, ORR sorted through the case records of the nearly 12,000 kids in its care. That same month, according to Politico, Lloyd instructed his staff to stop maintaining a spreadsheet tracking separated children and families, further delaying efforts to reconnect them. His office also neglected to review hundreds of case files despite orders from HHS Secretary Alex Azar, and until courts intervened, it insisted some parents pay for reunification travel. An incensed federal judge ordered ORR to transfer kids out of a facility south of Houston after a lawsuit alleged that staffers there had routinely administered psychotropic drugs to them without parental consent, denied them phone calls, and withheld water as a means of punishment. By the month’s end, Azar had directed ORR staff to report on reunification efforts to the agency’s emergency response team, effectively cutting Lloyd off from the day-to-day management. In August, ORR took the highly unusual step of asking a federal judge to unload the work of locating 410 parents who were deported without their kids to the American Civil Liberties Union and other nongovernmental organizations. (The judge denied the request.) Days later, an editorial in the Washington Post highlighted allegations of abuse at an ORR facility in Virginia, where half a dozen Latino teens said they’d been beaten and stripped naked. Some described being shackled to chairs with mesh bags over their heads. “It sounded like a scene from the Soviet gulag,” wrote the Post’s editorial board.

The criticism prompted Lloyd to break his silence, penning a terse letter to the editor defending the “excellent care” delivered by his office. The Friday the Post printed his letter, ORR still held 539 separated kids.

“Scripture has over 100 verses about welcoming the immigrant. That we are to love them as we love ourselves and as we love our own children,” says the Reverend Jennifer Butler, the CEO of the nonprofit Faith in Public Life, who has led delegations of clergy to the border to survey the family separation crisis. “I can’t comprehend how the head of an agency could claim to be pro-life and then not put everything they have into fixing this problem. A pro-life ethic has to extend to living children and to mothers. Instead he’s part of a system that separates nursing babes from their mothers’ arms. How pro-life is that?”

A week later, on a clear, warm day in Front Royal, Lloyd made the 10-minute drive to St. John the Baptist for that Sunday’s 10:30 a.m. Latin Mass. One of the morning’s readings came from Psalms: “When the poor one called out, the Lord heard, and from all his distress saved him.” Toward the end of the service, Lloyd and two other pillars of the congregation helped the priests administer Communion. After Mass was completed, children streamed out of the pews for Sunday school. They would rejoin their parents after the day’s lessons were complete.