Mother Jones; champja/Getty Images

When Erika Sherek was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016, she knew the road to recovery would be long and painful. Surgery and radiation therapy saved her life, but the treatment fundamentally changed her body. Because she stopped producing estrogen, the female sex hormone, Sherek, then 46, began to experience symptoms associated with menopause: vaginal dryness, urinary tract infections, and pain during intercourse. When sex with her husband became impossible, her doctor suggested vaginal laser therapy with a device called the MonaLisa Touch.

The MonaLisa Touch uses laser technology that has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for a host of skin treatments, including reducing the appearance of acne scars and excising small lesions. But lately the device has become popular among women who are using it for a very different reason: to “rejuvenate” the natural lubrication of their vaginas.

Countless women suffer uncomfortable and embarrassing symptoms—like vaginal dryness; burning, painful sex; or mild urinary incontinence—typically brought on by hormonal changes from menopause or cancer treatment. According to the manufacturer’s guide, the MonaLisa Touch could relieve these conditions, known collectively as genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), or vaginal atrophy, by boosting the vagina’s lubrication with three quick, gentle rounds of laser therapy. “They told me right up front that it wasn’t a 100 percent cure-all,” Sherek says. “They said you’re not going to feel like you’re 18 again, but it will help dramatically with the symptoms.”

But in late July, the FDA issued a safety alert, warning that the use of “energy-based” devices like the MonaLisa Touch had never been approved for treating vaginal conditions related to menopause. In fact, despite the hype, the safety and effectiveness of laser-based therapy for GSM have yet to be definitively proven. No randomized controlled trials, the gold standard of medical studies, have been published to show that this kind of laser therapy works better for women with GSM than placebos or other common remedies such as estrogen creams. And because it isn’t covered by insurers, the procedure is expensive—women report spending up to $2,500 for a course of treatment and up to $500 for “retreatment” a year later.

Facing limited treatment options, however, both patients and doctors believe that laser-based therapies may have merit. When the MonaLisa Touch arrived in the United States in 2014, patients who used it for GSM began to post online with positive, even life-changing results. The MonaLisa Touch was hailed as “The Laser That Could Save Women’s Sex Lives” by the Daily Beast, and online forums buzzed with enthusiasm. Sherek, who was one of the first patients to undergo the procedure at her local clinic, describes the MonaLisa Touch as improving her symptoms “500 percent,” but notes that she still has to use vaginal moisturizers and that the initial procedure was painful.

The MonaLisa Touch was one of the first in a line of laser-based technologies marketed toward women suffering from GSM. The Ultra Femme 360, made by BTL Industries, was cleared by the FDA to treat the appearance of wrinkles but was marketed online as “the shortest non-invasive radio frequency treatment available for female intimate parts.” Other companies said their devices improved vaginal irregularities and could be used to treat sexual dysfunction.

Sherek, a wedding and event planner from Montana, said she was aware of the lack of research into the devices when she began treatment with her usual, trusted gynecologist. But she’s concerned that other women may not be as well prepared. “I think a lot of people were under the impression that it was this magic wand,” she said.

That’s why, in late July, the FDA issued letters to seven manufacturers cautioning them against inappropriately marketing their devices. In a statement, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb went further, characterizing manufacturers as “bad actors” preying on vulnerable women, including cancer survivors. Treatments like the MonaLisa Touch, the agency said, could cause burns, scarring, and chronic pain. The agency told Mother Jones it had received 12 adverse event reports related to laser-based vaginal treatments since December 2015. “We are deeply concerned women are being harmed,” Gottlieb wrote.

Doctors are not breaking the law when they use devices like the MonaLisa Touch “off-label.” In fact, it is not uncommon for drugs and devices to be put to use beyond their FDA-approved treatment, particularly for cancer patients. “From a legal perspective, a doctor can prescribe or use anything off-label that they think is in the best interest of their patient,” said Loren Jacobson, assistant professor of law at the University of North Texas-Dallas.

Manufacturers, however, are required under federal law to be truthful in their marketing. That means, for example, not leading customers to believe their devices have been cleared by the FDA when they have not, or that medical evidence exists where it doesn’t. On its website, Cynosure, the manufacturer of the MonaLisa Touch, claimed its device was “a simple, safe, and clinically proven laser treatment for the painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” In a letter to the company, the FDA flagged this claim among others as being unsupported.

In a statement to Mother Jones, Cynosure’s parent company, Hologic, said it was aware of the FDA’s letter and was taking the agency’s concerns seriously. “Hologic has a strong track record of rooting our products in science and clinical evidence,” the statement said. “We are evaluating the letter in full and will collaborate with the agency to ensure all product communications adhere to regulatory requirements.”

Experts uniformly agree that more quality research into laser-based treatment for GSM is needed. Clinical trials have so far only used a small sampling of patients, and few have been compared against placebo controls. Additionally, many of the studies so far have been sponsored by device manufacturers, creating potential conflicts of interest.

At the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, however, the first randomized trial of laser therapy for GSM is about to be submitted for publication by pioneering gynecological surgeon Marie Paraiso. The trial, which began in March 2016, compares the effectiveness of vaginal laser therapy against vaginal estrogen cream in women with GSM. Low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy, which can be received in the form of a tablet, cream, or vaginal ring, is currently considered the best treatment for GSM, but doctors are cautious about prescribing it for survivors of breast or endometrial cancer, which can be hormone-sensitive.

“We were early adopters, but we are also early investigators,” Paraiso said of the MonaLisa Touch. While she notes that the data is not yet compelling, she believes laser therapy offers many of the same results as vaginal estrogen creams. For women who cannot or do not want to use hormone-based therapies, the treatment could offer a lifeline.

Take Sherek, whose doctor told her she would be an excellent candidate for laser therapy due to the extent of her condition and the fact she was a breast cancer survivor. “Because I can’t have any hormonal treatments, this was pretty much my only option for relief,” Sherek says. “I had lost hope.”

The tension surrounding the treatment of GSM is indicative of broader issues in the way women’s health issues have historically been under-researched and ignored. In 2010, the National Academy of Medicine found that research into conditions including women’s autoimmune diseases, maternal mortality, and most gynecological cancers had seen little or no progress over the past 20 years. The organization also found that women continued to be underrepresented in clinical trials, and that progress in women’s health had been slowed because researchers have historically failed to report research data by sex. As a result, information and treatment for health issues affecting women is often lacking. That leaves women searching for options.

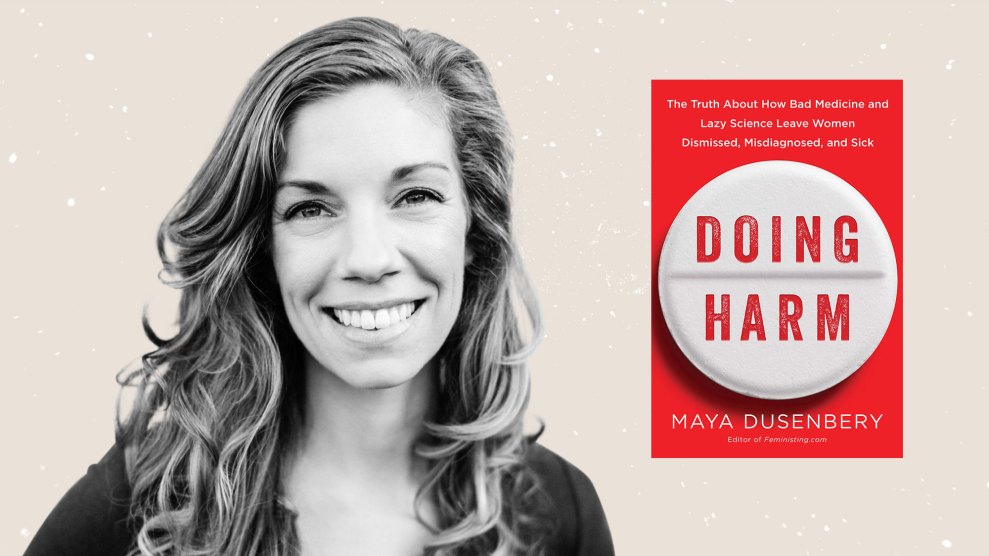

“There are so many women suffering from conditions that are really under-researched, that have few—if any—FDA-approved treatments specifically for them,” says Maya Dusenbery, author of the book Doing Harm. When women turn to alternative or off-label treatments, she says, the problem isn’t that they aren’t interested in FDA-approved care: That care is simply not available to them.

“Certainly, telling companies that their marketing should not overstate the evidence is important. But that’s different than saying [that] just because we don’t have the evidence yet means that we already know that this doesn’t work,” she says. “I think what’s so complicated and frustrating here is that it leaves individual patients on their own to figure out what is potentially effective.”

A few months have passed since her last round of treatment, and Sherek says she would recommend the procedure to other women—with one caveat. “It’s about having accurate information and understanding your own body,” she says. “You need to be responsible. You need to do your research. You need to ask the questions.” And that goes for doctors and the FDA, too.