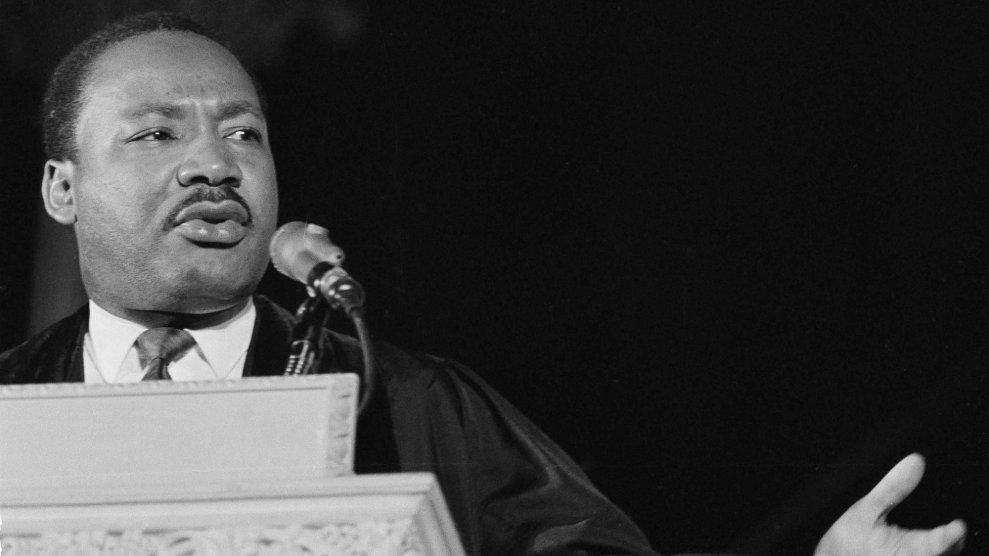

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speaks at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. just days before his deathJohn Rous/AP

Today marks 50 years since Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis, Tennessee. Dr. King had traveled to the city to stand with black sanitation workers, who were striking because of dismal pay and dangerous working conditions. The night before his death, Dr. King gave a speech to a crowd packed into a church that was eerily prophetic:

Like anybody, I would like to live a long life–longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.

The next evening, while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, King was shot by James Earl Ray.

The day of King’s assassination, Robert F. Kennedy, who had recently announced his presidential candidacy, was slated to appear in Indianapolis. In a predominantly black neighborhood, Kennedy announced that Dr. King was dead. As the crowd gasped, Kennedy gave a short speech invoking the death of his brother, President John F. Kennedy, and asking for prayers, unity, and peace:

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.

Kennedy would be assassinated just two months later in California.

As the news of King’s death spread, riots broke out in black neighborhoods across the country including Chicago, Baltimore, and Washington, DC, where President Lyndon B. Johnson sent in the Army and National Guard. In various cities, protesters destroyed property, burned and looted stores, and engaged in violent clashes with law enforcement.

While cities still smoldered less than a week after King’s death, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law, which prohibited housing discrimination.

Dr. King, who did not have much public support among white Americans, eventually ended up with a national holiday honoring his birthday and hundreds of streets named after him. But as Mother Jones reporter Jamilah King points out, many of these streets often suffer from poverty and segregation, the very things King fought against.

There are more than 900 streets in America named after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, and they either make good on his dream of desegregation, or mock it. Here, for instance, is MLK Drive in deeply segregated Chicago: pic.twitter.com/eM8aAz2Z99

— Jamilah King (@jamilahking) April 4, 2018

But there’s an explanation for why so many streets named after King are plagued by violence and inequality.

“Most of them are in black communities and through the structural racism that pervades the built in environment in the United States, these neighborhoods and streets were created to fail in a lot of ways,” Daniel D’Oca, a professor of urban planning at Harvard University told the Bay State Banner in 2016. “There were racist policies employed throughout the 20th century that you can look at to explain why these streets look the way they do.”

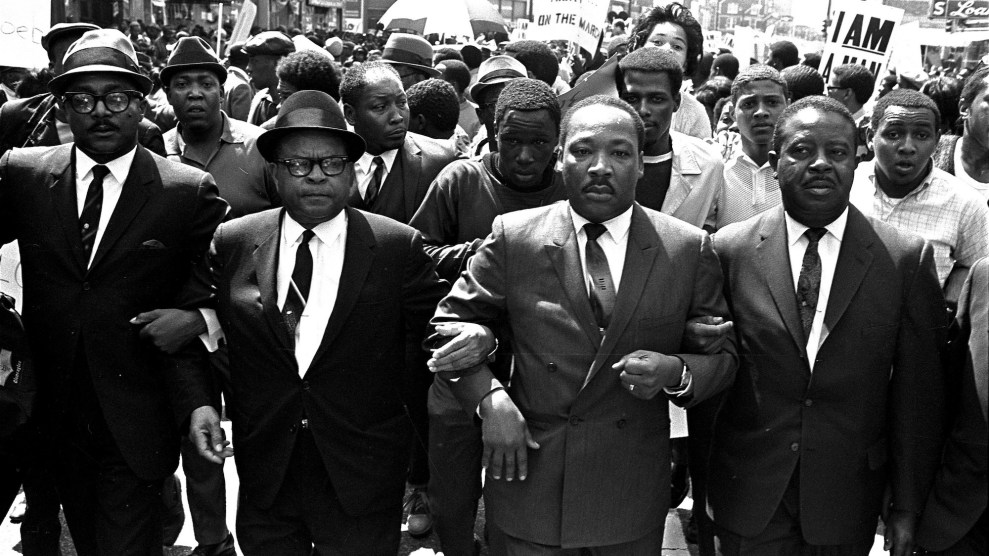

Today, rallies to commemorate Dr. King are expected across the country. In Washington, DC faith leaders are expecting thousands of participants at the Act Now! United to End Racism event. In Memphis, hundreds gathered for the I AM A MAN rally, a reference to the signs striking sanitation workers displayed 50 years ago.

I AM MAN Rally starting soon with an all star line up of civil rights activists, recording artists and congressional leaders. The rally is honor of the 1300 sanitation workers #MLK was fighting for in Memphis. @RevDrBarber will speak. #ABC11 #MLK50 #MLK50Forward #MLK50NCRM pic.twitter.com/R4iSBIMcds

— Tim Pulliam (@TimABC11) April 4, 2018

Decades after Dr. King’s death, Memphis sanitation workers are still fighting for their rights. “For a lot of these people, it is still 1968,” Maurice Spivey, chair of the union that represents the city’s sanitation workers told Mother Jones in March. “I know these folks saying, ‘A whole lot has changed.’ But a whole lot has stayed the same.”