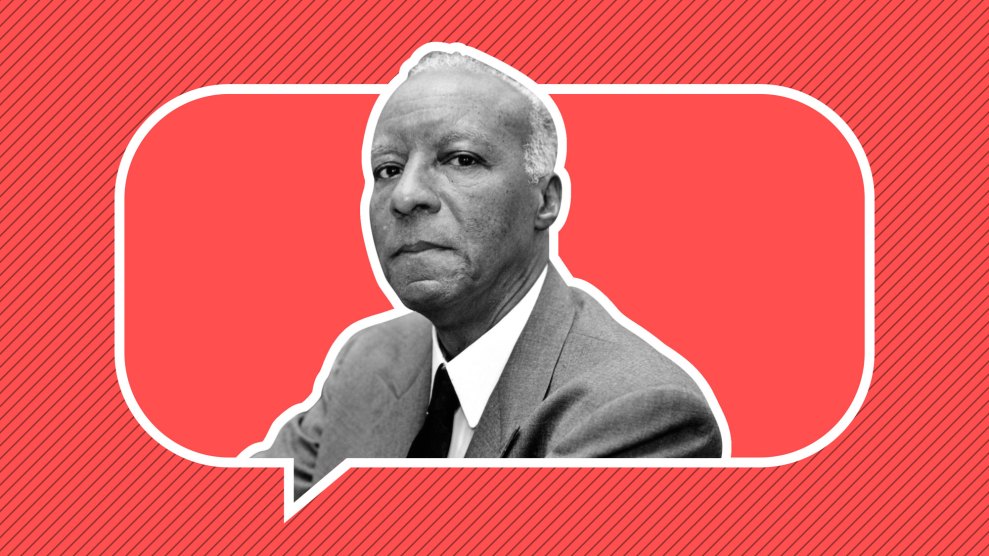

A. Philip Randolph pressured Roosevelt to bar employers from racial and ethnic discrimination when hiring for federal and war-time jobs in the months leading up to the U.S. entering World War II.Mother Jones illustration

The United States government officially recognized Black History Month in 1976—decades after Carter G. Woodson, often thought of as the “Father of Black History,” started setting aside a week a year to honor black Americans. His organization, now called the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, sought to promote the study of black history when the contributions of black Americans were absent from textbooks.

While black history is included in school curriculums across the country now, it shouldn’t be siloed off and considered separate from the rest of history says Margot Lee Shetterly, author of Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Who Helped Win the Space Race, a New York Times bestseller that was adapted into an Oscar-nominated film. Not only are these stories separated, but many important stories are left out altogether, giving us what Shetterly describes as an incomplete view of our past and who we are as Americans.

“One of the things that’s most important, is to see these stories not strictly as…black stories, though they certainly are, but to really see these are American stories,” says Shetterly. “We often, particularly in this country, balkanize these stories and relegate them to one bucket or another bucket. But when we step back and see the bigger picture, we see how all of these different parts of our country have contributed to us being what we are today.”

One of the many black Americans she would like to see included in mainstream American history is A. Philip Randolph, the man who pressured Roosevelt to bar employers from racial and ethnic discrimination when hiring for federal and war-time jobs in the months leading up to the U.S. entering World War II. “His actions really opened those jobs to any number of Americans and created long-term economic prospects for many people including the women of Hidden Figures,” she explains.

Figures like Randolph are left out, in part, because black history is often oversimplified to just focus on slavery, prominent icons of the civil rights movement—like Martin Luther King Jr., of course—and the election of Barack Obama. “Usually we go from the civil war and somehow magically end up in the civil rights movement, as if black people weren’t protesting the entire time,” explains Theresa Runstedtler, the department chair of the Critical Race, Gender and Culture Studies Collaborative at American University.

Runstedtler says one under-appreciated activist pushing for equity during that time period was Ella Baker, who organized for black economic justice and women’s rights in the 1930s, and became a leader in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the 1940s. Baker left the NAACP, though, because she thought the organization was too focused on legal strategies and too hierarchical. She wanted to pivot to a more grassroots approach. “She really believed in the strategy of empowering everyday people to be the leaders of their own struggle,” Runstedtler says. “So she really wasn’t into this idea of the charismatic male leader who’s going to pull everyone out of misery.” Baker worked behind the scenes, doing things such as setting up a meeting between student leaders of the Greensboro sit-ins, which led to the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and mentoring young activists.

Baker wasn’t someone who regularly made herself visible in the media, and Runstedtler points out that many black women who focused their energy on grassroot organizing and “were invested in creating institutions and mentoring people,” are often underrepresented in the retelling of history because it’s “often less sexy” than giving lectures before large audiences. “I think, in some ways, this narrative that erases all of that work, also can be disempowering for people because it makes it seem as if leaders are the only ones who can instigate social change,” Runstedtler says. “But if we look at all of the…people who were doing the grunt work of making the movement, that’s actually how organizing happens.”

Stories of early black success are also left out explains Shomari Wills, whose new book highlights the first wealthy black Americans who created jobs for former slaves in the years after emancipation and helped fund black liberation movements. Wills says he wrote the recently released Black Fortunes: The Story of the First Six African Americans Who Escaped Slavery and Became Millionaires because he wanted to write about some of the economic history of black America that’s left out of the mainstream. “I just wanted to shine a light on some of these folks because they were so crucial during a time when black folks were really trying to get on their feet,” Wills says.

Mary Ellen Pleasant, for instance, helped former slaves find jobs and housing. She also financially supported John Brown, a white abolitionist who does make it into our mainstream history books for planning a slave rebellion at Harper’s Ferry. “Black abolitionists are really an overlooked aspect of history,” Wills says. “We give a lot of ink on a lot of the white abolitionists because they had the ability to move more freely and sometimes their impact was more conspicuous than black abolitionists [who] had to worry about their own freedom, too. We don’t talk about how much African Americans did to free themselves.” This, he says, “fuels a white savior myth instead of what actually happens, which is [that] folks work together.”

Shetterly explains having these narratives included in our collective understanding of history is important, pointing to the black women mathematicians she writes about who helped America win the space race. They defied misconceptions about what black women were capable of. “If you see that this is something that existed in the past, then it’s that much easier to imagine that person contributing in that way in the future,” she says. “Our perception of our past really sets the parameters for our understanding of what’s possible in the future.”

Now, we want to hear from you

For Black History Month, we want to hear about the people who’ve helped broaden your understanding of our American past and shape your perspective of present-day events. Well-known or not, we want to know: When has a figure from black history—or current history—made an impression on you? Did their story motivate you to do something? Tell us all about them.

[contact-form to=”talk@motherjones.com” subject=”Black History”][contact-field label=”YOUR STORY” type=”textarea”][contact-field label=”NAME” type=”text”][contact-field label=”EMAIL” type=”text”][contact-field label=”CITY, STATE” type=”text”][contact-field label=”AGE” type=”text”][/contact-form]

We may share your response with our newsroom and publish a selection of stories which would include your name, age, and location. Your email address will not be published and by providing it, you agree to let us contact you regarding your response.

Image credit: Associated Press