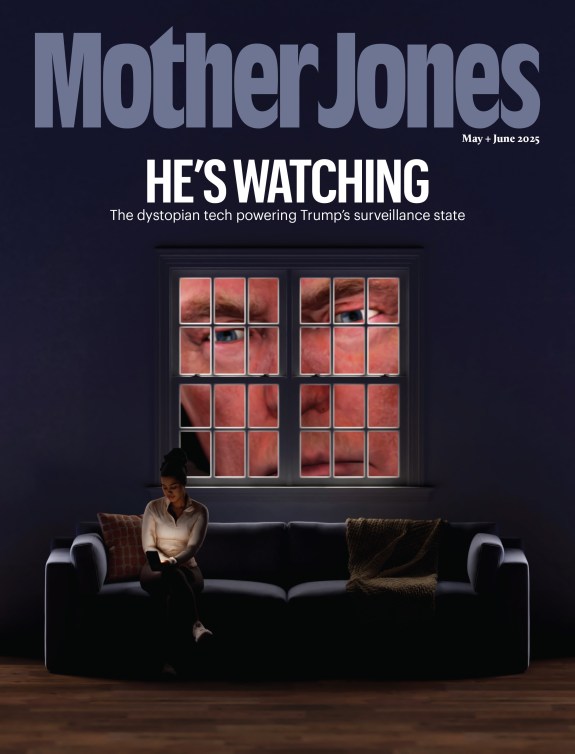

Student Anne Harris register to vote Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2017, at Lake Michigan College, in Benton Harbor, Mich. Herald-Palladium via AP

Thirty years ago, the United States had a big problem. Barely half of eligible voters had cast a ballot in the 1988 presidential election—the lowest voter turnout since the 1920s. In an effort to increase participation, Democrats in Congress—backed by a few Republicans— drafted the National Voter Registration Act, a bill that would require states to allow voters to register at Department of Motor Vehicle offices and other public agencies.

Sen. Mitch McConnell, a Kentucky Republican, led the opposition to the legislation. “This bill wants to turn every agency, bureau, and office of state government into a vast voter registration machine,” McConnell said in 1991. “Motor voter registration, hunting permit voter registration, marriage license voter registration, welfare voter registration—even drug rehab voter registration.” That same year, McConnell, who is now the Senate majority leader, wrote that “low voter turnout is a sign of a content democracy.”

The NVRA passed Congress in 1992, but President George H. W. Bush vetoed it. Congress passed it again a year later, and this time President Bill Clinton signed it into law, calling it “a sign of a new vibrancy in our democracy.” The “motor voter” law, as it became known, was an immediate success. In its first year in effect, more than 30 million people registered or updated their registrations through the NVRA. Roughly 16 million people per year have used it to register ever since.

But in recent years, Republicans have sought to gut the law. In 2013, the Supreme Court weakened a key part of the Voting Rights Act, ruling that states with long histories of voting discrimination no longer needed to clear their election changes with the federal government. After winning that fight, Republicans are now going after the NVRA in what voting rights advocates say is a thinly veiled effort to make it more difficult for Democratic-leaning constituencies to register to vote—and far easier for state officials to remove them from the voter rolls. “We’re seeing a coming fight over how voter rolls are maintained,” says Dale Ho, director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project. “It’s a new front in the voter suppression battles.”

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear the newest challenge to the law, concerning whether Ohio can remove voters from the rolls who don’t vote over a six-year period. If a voter in Ohio misses an election, doesn’t respond to a subsequent mailing from the state, and then sits out two more elections, he or she is removed from the registration list, even if this person would otherwise be eligible to vote. Critics of this process say it turns voting into a “use it or lose it” right and will open the door to wider voter purges.

Ohio purged 2 million voters from 2011 to 2016, more than any other state, including over 840,000 for infrequent voting. At least 144,000 voters in Ohio’s three largest counties, home to Cleveland, Columbus, and Cincinnati, have been purged since the 2012 election, with voters in Democratic-leaning neighborhoods twice as likely to be removed as those in Republican-leaning ones, according to a Reuters analysis.

A federal appeals court ruled in September 2016 that the state’s purging of infrequent voters violated the NVRA, which states that someone cannot be removed from the rolls “by reason of the person’s failure to vote.” As a result of that ruling, 7,500 people who had been purged from the rolls were reinstated and were able to vote in the 2016 election.

Ohio says it should be allowed to remove these voters from the rolls under the NVRA, claiming that “a failure to respond to a notice— not a failure to vote—is the sole proximate cause of removal” under its purge program. Ohio adds that if the Supreme Court finds that the NVRA does prohibit its actions, it would raise “serious constitutional questions” about the law. A supporting brief by the American Civil Rights Union, a conservative group that has sued states to force aggressive voter purges, says that if “the NVRA indeed prohibits the states from utilizing inactivity as a factor that leads to deeming a registrant ultimately to be unqualified—as the lower court found—then the NVRA intrudes on the important federalist balance in the Constitution.”

The Ohio case isn’t the only way Republicans are trying to weaken the motor voter law.

In 2013, Kansas implemented a law championed by Secretary of State Kris Kobach that required people to show a birth certificate, passport, or naturalization papers to register to vote. The proof-of-citizenship law ultimately blocked 1 in 7 eligible voters who attempted to register, nearly half of whom were under 30. The ACLU sued, alleging that the law violated the NVRA by preventing people from registering at the DMV. The ACLU won a preliminary injunction in 2016, with a federal appeals court ruling that if the law remained in effect, “there was an almost certain risk that thousands of otherwise qualified Kansans would be unable to vote in November.”

After the election, Kobach drafted federal legislation to amend the NVRA to allow states to require proof of citizenship for registration. He shared his draft with Donald Trump and his top advisers during a meeting in November 2016. Kobach, who later became the vice chair of Trump’s now-defunct election integrity commission, fought relentlessly to shield this proposal from the public and was fined by a federal court last year for telling the court that “no such document exists.”

The ACLU’s case against Kobach is going to trial in March. If Kobach wins, the precedent will allow more states to pass similar proof-of-citizenship laws. If he loses, Kobach will no doubt intensify his efforts to amend the NVRA. “The NVRA has been abused by organizations like the ACLU,” Kobach told the New York Times Magazine last year. “They’ve twisted the words to try and say it prevents proof-of-citizenship laws.”

Even as Republicans are seeking to weaken the NVRA, three conservative lawyers who worked in the George W. Bush Justice Department are turning the law on its head by attempting to use it to force states and localities to engage in Ohio-style voter purges. As my colleague Pema Levy reported, they’ve targeted nearly a dozen states, along with small counties in places like Mississippi and Texas with large minority populations:

The letter to Noxubee County [Mississippi] alleged that the county was violating a federal law that requires states to keep their rolls up to date. The commissioners maintained that they were following the law. In fall 2015, the ACRU’s [American Civil Rights Union] attorneys began to push the commission to sign a consent decree that would commit the county to vigorous vetting of its registered voter list in order to avoid a lawsuit. Among its provisions, the draft decree would require the commission to send a non-forwardable notice to all registered voters asking them to confirm their eligibility. Every voter who did not fill it out and return it would be put on a list of inactive voters, and anyone on that list who failed to vote in two federal elections would be removed from the rolls.

For its part, the Trump administration has come out squarely in support of voter purges. The Obama Justice Department opposed the Ohio purge program, but Trump’s DOJ abruptly switched sides in the case. “After this Court’s grant of review and the change in Administrations, the Department reconsidered the question,” the DOJ informed the Supreme Court in August. “It has now concluded that the NVRA does not prohibit a State from using nonvoting as the basis for sending a [removal] notice.”

In June 2017, the DOJ also sent a letter to 44 states informing them that it was reviewing their voter list maintenance procedures and asking how they planned to “remove the names of ineligible voters.” If Ohio wins at the Supreme Court, it will “certainly embolden” the department and GOP-controlled states to undertake aggressive voter purges, says Vanita Gupta, who headed the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division under Obama and is now president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

And that would open the door to broader challenges to the NVRA. “It’s a hugely significant case,” Gupta says. “If the court comes out with a broad ruling that says inactivity in voting is sufficient proof to kick a voter off of the rolls, that could have broad implications across the country for how voters are purged off the rolls per the National Voter Registration Act.”