North Carolina NAACP President Rev. Anthony Spearman speaks at a rally in Raleigh for judicial fairness on January 10.Julia Wall/The News & Observer via AP

North Carolina’s Republican-led legislature has repeatedly passed controversial laws in recent years only to have them thrown out in court. Now the legislature is striking back with an effort to radically transform the makeup of the state’s courts.

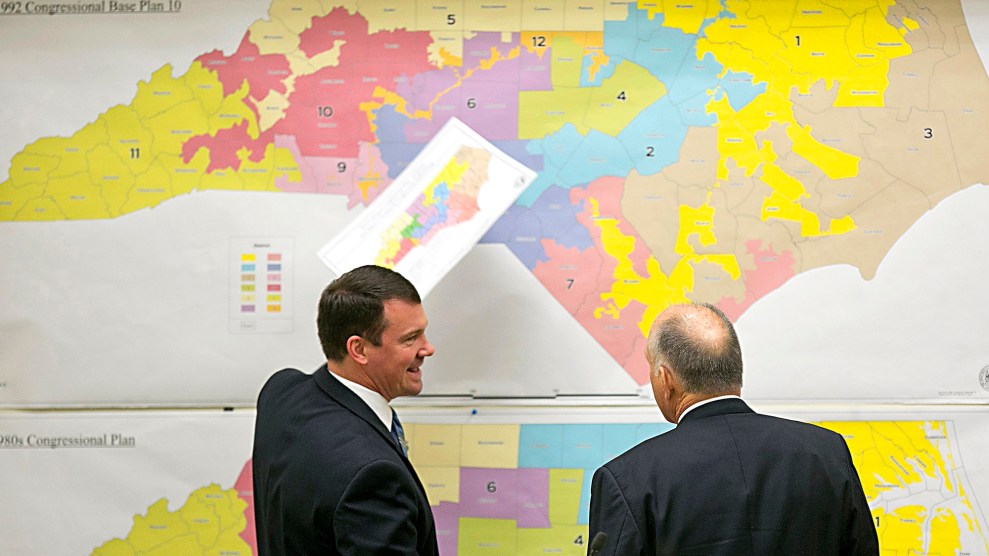

Courts have overturned 14 laws passed by the legislature since 2011, including redistricting maps for the House of Representatives and the state legislature that one federal court called “among the largest racial gerrymanders ever encountered by a federal court.” Sweeping voting restrictions passed by the legislature in 2013 suffered a similar fate, with a federal appeals court saying they targeted “African Americans with almost surgical precision.” The legislature’s Republican supermajority hasn’t fared any better in state courts, which have blocked GOP efforts to strip teachers of tenure and to prevent the state’s Democratic governor, Roy Cooper, from appointing a majority of commissioners on state and local boards of elections.

Now the legislature has embarked on an unprecedented plan to transform the state’s courts by gerrymandering judicial maps to elect more Republican judges, preventing Cooper from making key judicial appointments, and seeking to get rid of judicial elections altogether. Cooper calls it an attempt to “rig the system.”

The GOP attack on the courts began in 2013, when the legislature ended public financing for judicial elections, which had helped elect more minority and women judges. These efforts accelerated after liberal judges gained a 4-3 majority on the North Carolina Supreme Court in 2016. The legislature promptly changed the judicial election system by requiring candidates to represent a political party, the first time a state has moved from nonpartisan to partisan judicial elections since 1921. Republicans reasoned that having to identify as a Democrat would make it harder for liberal judges to win in a GOP-leaning state. The legislature then canceled judicial primaries, giving incumbents (who were mostly Republicans) an advantage due to their name recognition in races where voters were asked to choose among many candidates. Republicans also eliminated seats on the court of appeals to prevent Cooper from appointing three new judges.

Now the legislature is taking up a host of controversial new proposals in a special session, including redrawing judicial maps for the first time in roughly 50 years to put more Republicans on the bench. The new maps would likely give Republican judges 70 percent of seats on North Carolina’s superior and district courts, according to an analysis by the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, a voting rights group based in Durham. The groups calls the new lines “a gross political gerrymander of our state’s legal system, designed to ensure that Republican judges will be elected in a disproportionate number of districts statewide.”

Republicans would pick up seats by pitting Democratic incumbents against each other. About 70 percent of the judges who would be forced to run against other incumbents under the new maps are Democrats, according to the SCSJ analysis. The Republican maps would also reduce the number of minority judges by pitting half of African American judges against other incumbent judges in cities like Durham and Greensboro. The new districts “bear an uncanny resemblance” to the racially gerrymandered state legislative maps struck down in court, the analysis found.

“These proposed changes would erode the public’s faith in the courts,” says Tomas Lopez, executive director of the voting rights group Democracy NC, which is lobbying against the new maps. “They come from the same place as the state’s badly gerrymandered maps and targeted voting restrictions.”

Republicans are also floating a proposal to require all state judges to run for election every two years—instead of the current four-year terms for district court judges and eight-year terms for superior court, appeals court, and supreme court judges—which would give North Carolina the shortest judicial terms in the country. “Some would argue that we do have some activist judges, and the thought would be if you’re going to act like a legislator, perhaps you should run like one,” Republican state Rep. David Lewis told radio station WUNC. Republicans are particularly upset that the liberal majority on the state supreme court is safe at least through 2022, allowing the court to block GOP attempts to gerrymander electoral maps after the 2020 census.

Some Republicans, like state Senate leader Phil Berger, favor a more radical solution: ending judicial elections altogether. Under this proposal, the legislature would nominate candidates for the bench, and the governor would have to choose from among them to fill new vacancies, effectively allowing Republicans to select all judges. (Republicans hold a 50-seat advantage in the legislature.) Voters must approve this system through a constitutional amendment, which Republicans could put on the ballot in May, when voters will select state legislative candidates in the primaries. “This is just a way for legislators to cherry-pick their judges because they’re disappointed with how the judiciary hasn’t ruled their way,” says Melissa Price Kromm of North Carolina Voters for Clean Elections, a government watchdog group that is leading opposition to the judicial changes. South Carolina and Virginia are currently the only states where state legislatures choose judges.

Even some Republican judges have reacted with dismay to the legislature’s changes. When the legislature reduced the size of the appeals court to block Cooper from appointing new members, Republican Judge Douglas McCullough retired early to allow the Democratic governor to name his successor. “I did not want my legacy to be the elimination of a seat and the impairment of a court that I have served on,” he said.

North Carolina is a microcosm for the rush by national Republicans to remake the courts before potentially losing power after the 2018 congressional elections. “In the same way we’re seeing Congress rush to approve Trump’s judicial nominees before possibly losing the Senate, the North Carolina general assembly is rushing to pass sweeping judicial changes before they lose their supermajorities,” says Price Kromm. North Carolina, she says, is a test case. “If North Carolina succeeds in being able to gerrymander their judges and cherry-pick their judges, it will spread like a disease across this country.”