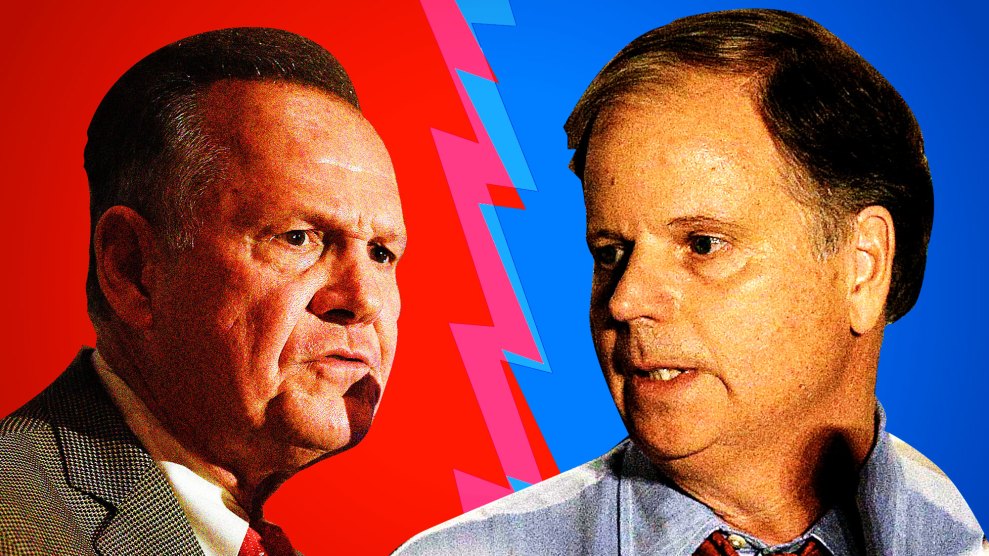

Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore speaks during a Promise Keepers 2003 Mens Conference, Saturday, Sept. 6, 2003 at Philips Arena in Atlanta. Gregory Smith/AP

Former Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore, who is now the Republican candidate for Alabama’s open Senate seat in the special election Tuesday, has spent nearly two decades issuing repeated battle cries to right-wing Alabama evangelicals. It’s his faith, he says, that motivates his actions, and it’s his faith that he uses to excuse those actions when they land him in trouble. When, for instance, he infamously installed a Ten Commandments monument in the Alabama Judiciary Building, he said that “to restore morality we must first recognize the source from which all morality springs.” His refusal to remove it was, famously, what got him suspended from the bench, at least for the first time. And then, after the Supreme Court ruled to legalize gay marriage, he said, “Welcome to the new world. It’s just changed for you Christians. You are going to be persecuted according to the U.S Supreme Court dissents,” and instructed Alabama judges to not uphold the federal court ruling. It was the move that got him suspended for the second time and ultimately removed from the Alabama Supreme Court. In both instances, he refused to back down or admit wrongdoing.

Moore’s seemingly steadfast commitment to Christian ideals has earned him the unwavering support of national evangelical Christian leaders like James Dobson, founder of Focus on the Family, and Franklin Graham, president of Samaritan’s Purse and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association—and also of much of the statewide Christian community. “I often ask God to raise up men and women of faith who will govern the nation with biblical wisdom,” Dobson said in his endorsement of Moore in August. “I believe Judge Moore to be such a man for this time.”

All this, of course, was before allegations started to come to light in early November of sexual misconduct from at least nine women, some of whom were underage at the time of the encounters. But still, Moore’s place in the local evangelical community has remained relatively solid and the race is still neck-and-neck with Democratic opponent Doug Jones. A recent Washington Post-Schar School poll says that 78 percent of white Protestant evangelical voters are planning to vote Moore, despite the stories of sexual misconduct. Moore’s wife posted a letter from 50 pastors (four of whom asked their names to be removed after she did so) who allegedly signed the document that proclaimed Moore is an “immovable rock in the culture wars,” and has met attacks with a “rare unconquerable resolve.” Much of this support likely comes from the fact that Moore is pro-life, while his opponent is publicly pro-choice. A 2014 Pew Research Center study found that 58 percent of Alabamians think abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, and only 37 percent believed the opposite.

That’s at least the case for Pastor David Floyd, who has spent the last 34 years preaching at Marvyn Parkway Baptist Church, a small but tight-knit church in the just-shy-of-30,000 eastern Alabama town of Opelika. His vote, he says, will go to Moore without question.

“I don’t believe he’s guilty of these allegations,” says Floyd, who signed the letter in support of Moore. “And that’s all they are—allegations.” He considers Moore to be a persecuted man, which he says “comes with living a godly life” in a sinful world. “It’s no strange thing—the Lord himself said the world hated him,” he says.

What’s largely lost in the media coverage, though, is that many Christians in the state do not, in fact, support Moore—and some of them are making the case that to support Moore is actually at odds with what the Bible instructs. The associate director of Greater Birmingham Ministries and a former Church of Christ pastor, Rev. Angie Wright, has been one of the most vocal Christian leaders standing against Moore. In November, she helped organize a letter from 59 Christian ministers that says Roy Moore is “not fit for office.”

When it comes to Moore, the most pointed difference between Wright and Floyd is likely their view of the women who have come forward with stories of sexual assault and abuse. “I do believe the women, I believe that their stories have been corroborated strongly, and I think it is part of a larger consistent deeply disturbing pattern of abuse of power,” Wright wrote to Mother Jones in an email.

But these women aren’t the only reason Wright feels compelled to speak out against Moore.

“Even before the recent allegations of sexual abuse, Roy Moore demonstrated that he was not fit for office, and that his extremist values and actions are not consistent with traditional Christian values or good Christian character,” reads the letter Wright helped organize. “He and politicians like him have cynically used Christianity for their own goals. But Roy Moore does not speak for Christianity, and he acts in ways that are contrary to our faith.”

The real sticking point for Wright is one crucial Bible verse. Christians are commanded in the Book of Matthew to serve “the least of these”—which some Alabama Christians might interpret as victims of sexual assault, but many others, including Floyd, interpret primarily and most importantly as the unborn. As Wright explains, “We feel like [Moore] does not represent the essence of Christianity which for us is love and justice and mercy and care for the least of these.”

Wright, in contrast to Floyd, sees Moore as anything but godly and the things that draw other Christians to Moore—the Ten Commandments, the disavowal of same-sex marriage—she calls “an abuse of power.”

“We feel like it’s important to reclaim a Christian voice that represents more of the essence of our faith,” Wright explains. “We’ve seen a lot in the South of politicians who wear their Christianity on their sleeve and use it as a way to get votes.”

But that’s exactly the kind of call-to-action that inspires the support of other Christians in the South who feel attacked for their beliefs and caught in the middle of the culture wars. During the incidents with the Ten Commandments monument and the defiance of the same-sex marriage ruling, Moore “was willing to put his job on the line,” Floyd says. “That shows me a man that’s principled about what he’s doing—he’s not in it for money, he’s not in it for fame or fortune.”

Further, Wright argues that Moore’s aggressive positions on other religions and homosexuality are unacceptable. Moore has called Islam a “false religion” and said that practicing Muslims should not be allowed in Congress. He has said “homosexual conduct should be illegal,” has compared homosexuality to bestiality, and has claimed children need to be protected from it because it is an “inherent evil.” Wright says, as a Christian, she cannot support this kind of conduct—it alienates people from the church and twists her faith into something unrecognizable to her community. It’s the people harmed by this inflammatory rhetoric, says Wright, that are also “the least of these”—the LGBT community, Muslims, people of color. She notes Moore has also supported policies that have hurt low-income families and children. She says the question of abortion is “a hard one,” and she understands and respects where other Christians are coming from when they say it is the bright line they cannot cross. But it is not that for her.

Wright is part of a ministry that emphasizes social justice and equality and is located in Birmingham, a city that leans more Democratic than the rural areas that surround it, so it’s no real surprise that her views on Christianity differ from a preacher at a small Southern Baptist Church in Opelika. Wright does not identify as an “evangelical,” she says, because of the conservative Christian connotation the word has developed, but she does still see herself as someone compelled to “spread the good news” of the gospel. She notes wryly that the word originates from that meaning, which is void of any political connotation. She worries that many voters are being used by politicians who abuse their faith, the most powerful motivator Christians have, as a way to benefit themselves.

“We’ve been manipulated into thinking that if you’re a Christian, you vote Republican, and that’s a false dichotomy,” she says.

Her voice, though, while vastly different from that of Floyd and many of her peers, is still a crucial one. And she won’t let it be wasted. She plans to vote for Jones tomorrow and will do so because she sees him as a man who has a “quiet faith” that is steadfast, even if it’s not as overt as Moore’s. She is concerned that there’s a type of Christianity that is loud, shrill, and sensationalist that gets the most attention, even if it’s not representative of the Christians she knows in Alabama.

“For people in other regions,” she says, “it’s easy for them to caricature people from states like Alabama, and unfortunately, we do a lot of things that fit into that caricature.”

This post has been corrected to better reflect the nature of the allegations against Moore.