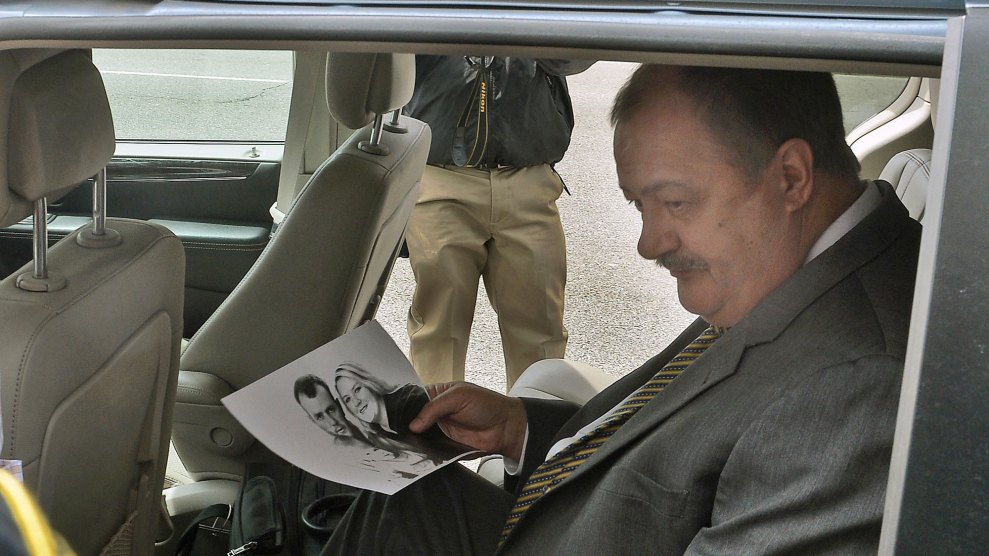

As he left a federal courthouse in West Virginia in 2016 after being sentenced to a year in federal prison, Don Blankenship was handed a picture of a miner who died at Massey Energy's Upper Big Branch Mine in 2010.F. Brian Ferguson/Charleston Gazette/Associated Press

Don Blankenship is running for Senate. Yes, the Don Blankenship. On Wednesday West Virginia station WCHS reported that the former Massey Energy CEO, fresh off a one-year stint in a federal prison for conspiring to commit mine-safety violations in the run-up to the deadliest mining disaster in decades, has filed paperwork to run in next year’s Republican Senate primary. He’ll join a crowded field, including US Rep. Evan Jenkins and state Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, in the race to take on incumbent Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin.

Blankenship was a towering figure in state and national politics until quite recently. He turned Massey into one of the nation’s largest coal producers by busting unions, strong-arming smaller operators, and flouting a raft of federal environmental and safety regulations. And he took that same approach honed in Mingo County to Charleston with great success. As I wrote in a profile in 2015:

The irony is that, even at the nadir of Blankenship’s power, his ideology is ascendant. He transformed West Virginia not just physically (entire towns have been wiped out by Massey’s footprint), but politically. Now, by playing off fears of creeping government involvement, the coal industry has strengthened its grip on state politics. Lawmakers friendly to the industry, with financial support from Blankenship, have won sweeping victories at the ballot box and used their mandate to roll back health and safety regulations while trumpeting the survival-of-the-fittest capitalism that was Blankenship’s gospel. The man on the mountaintop may have fallen, but the widespread impact of his legacy shows no signs of diminishing.

Ultimately, Blankenship’s bullying style did him in. In 2010, 29 people died in an explosion at Massey’s Upper Big Branch Mine in southern West Virginia. In the year prior to the explosion, federal Mine Safety and Health Administration inspectors had shut down portions of the mine for safety violations 48 times, and federal prosecutors would later discover that Blankenship’s subordinates employed a coded radio channel to stifle MSHA inspectors during visits. Much of his 2015 trial centered on the conversations Blankenship had recorded with subordinates prior to the explosion, in which he acknowledged his company’s high-wire act and conceded that “if it weren’t for MSHA, we’d blow ourselves up.”

Since getting out of prison in May, Blankenship has gone to great lengths to change the narrative about the events surrounding his conviction. In September, while he was already flirting with a Senate bid, he began running ads statewide in West Virginia, blaming the Upper Big Branch disaster on MSHA itself, and holding Manchin culpable for not properly scrutinizing the agency. Never mind that both state and federal investigations of the disaster faulted Massey. In a post-Trump world, where even the most debilitating allegations can be dismissed or forgiven, you can almost see the gears turning in Blankenship’s head.

Still he’ll face steep odds getting out of the primary, and not just because he’s freshly released from prison and, until recently, had claimed to be a resident of Las Vegas. In the run-up to his trial in 2015, Blankenship’s own attorneys sought to move the trial out of the state of West Virginia entirely for fear that he was so unpopular in his home-state he couldn’t get a fair trial. Instead, they proposed to hold the trial of a Mingo County coal baron in Baltimore, Maryland. A 2016 survey by Public Policy Polling found that just 10 percent of West Virginians had a favorably opinion of Blankenship, and 60 percent believed his prison sentence was too light. A lot has changed in the two years since Blankenship was convicted. But maybe not that much.