James Weldon Johnson.Mother Jones illustration

On a cloudy day in May 2015, several hundred Howard University seniors, myself included, filed into the school’s main quadrangle for commencement, a ceremony that kicked off with “The Star Spangled Banner.” I can’t honestly recall whether my fellow black students sang the words that day, but many typically did not. The America whose praises we were called upon to sing rarely returned the sentiment, and more often treated us like outcasts. We’d been reminded of this just weeks earlier, when Walter Scott of North Charleston, South Carolina, was shot in the back five times while fleeing from a cop, the latest in a seemingly endless list of of black men to have their lives cut short by police officers.

But the crowd was galvanized as we moved to the next song on the program. It was one we usually sang as a matter of routine, but on that day we heard it as a rallying cry, and sang it proudly and passionately—fists raised skyward in defiant assertion of a blackness that we loved even if the rest of the nation did not. The song was “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” For us, it had another name: the black national anthem.

Unless you attended one of the historically black colleges that pair “Lift” with the official national anthem at ceremonies and sporting events, or you spent a lot of time in black churches, in black civil rights spaces, or in majority-black grade schools, you might never have heard the song. But for much of the last century it was a staple of black life in America.

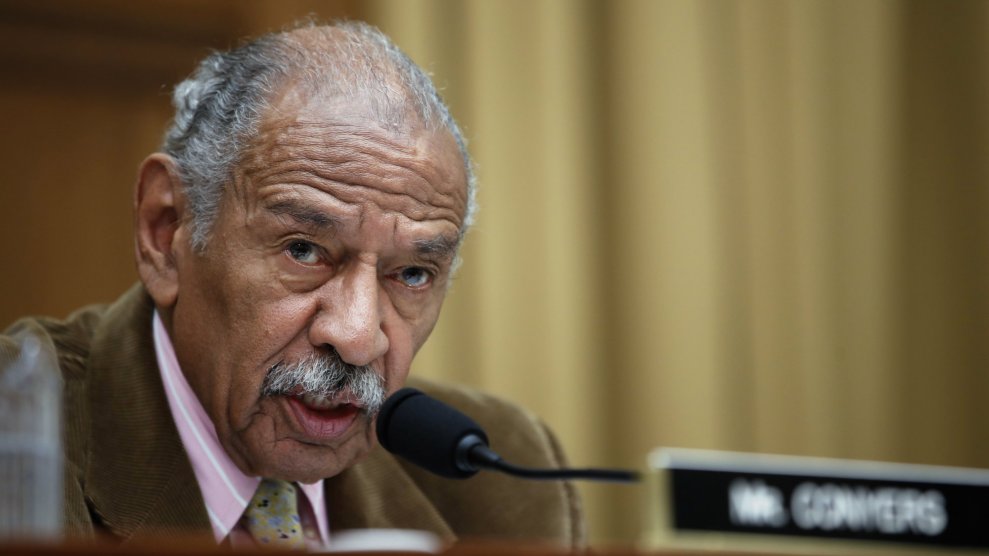

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” was first unveiled at a school showcase in 1900 marking what would have been Abraham Lincoln’s 91st birthday. It was penned by James Weldon Johnson, a graduate of the historically black Atlanta University (now Clark-Atlanta).

At the time, Johnson was a writer and the principal of a colored school in Jacksonville, Florida. (He later became a civil rights activist and US ambassador.) Members of the community had asked him to write a speech for the Lincoln affair. Instead, he wrote a hymn (his brother composed the music) and taught it to his 500 students.

Their performance was a hit. The song caught on in black Jacksonville and began spreading throughout the South. Churchgoers would even paste the lyrics on the backs of hymnals, says Imani Perry, a professor of African American studies at Princeton University whose book about the song, May We Forever Stand, is due out in February. Black newspapers and journals published the lyrics to “Lift,” and by 1906 they were calling it “an anthem for the Negro people.” (Sheet music for the song was imprinted with the subtitle “Negro National Anthem” beginning in the 1960s.)

During the 1910s, many black schools and colleges—Howard included—adopted “Lift” for their graduation ceremonies, and the K-12 schools incorporated it into “daily or weekly rituals” according to Perry: “So kids are singing it at segregated schools at assemblies—sometimes every morning.” The NAACP adopted “Lift” as its official song in 1921. (Johnson had become an executive in the organization.) And when Negro History Week (now Black History Month) was established five years later, Perry says, teachers started using the song to teach vocabulary and history.

Shana Redmond, a professor of musicology at the University of California-Los Angeles, says many of those teachers relied on “Lift” to “instill in their students those things that would best arm them” for a hostile world. “One of those things was about pride in self, about knowing your own heroes, your own ancestors.”

James Weldon Johnson (right) and his brother J. Rosamond Johnson review sheet music for “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

ASCAP/Wikipedia Commons

At the time Johnson wrote his hymn, lynchings had recently hit their peak in the South, the fall of Reconstruction remained an open wound, and offensive caricatures of blackness were pervasive. Patriotic odes like “The Star Spangled Banner” and “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” were popular, too, but black southerners were hungry for a cultural product that spoke to them.

“Lift” was that product. “It was the first widely circulated song that tells the story of black Americans, right at the time when black people are building institutional and civic life, as black people are imagining themselves,” Perry says. Johnson depicted blackness as “proud and prideful, as progressing forward, and as enduring, as empowered,” Redmond told me. “It was not solely an ode to this so-called Black Emancipator.”

The 1814 poem that became “The Star Spangled Banner” was something radically different, coming from a slave owner who was open in his disdain for the black race. “There was a scorn for blackness,” Redmond says. Many historians read part of Francis Scott Key’s third stanza as a celebration of the deaths of slaves who escaped to fight against their captors, siding with the British during the War of 1812. “But it’s also, to a certain extent, that blackness was not considered, in the least, part of the republic.”

And whereas “Lift” speaks to a future black folks can aspire to, Redmond adds, the anthem “is really not about a future—other than a future already proscribed by what is assumed as a constant greatness.”

So by 1931, when “The Star Spangled Banner” was officially codified as America’s anthem, black people already had a song they were treating as their own—which spread further as African Americans migrated north and west during World War I, seeking new opportunities and fleeing the violence of Jim Crow. Black intellectuals debated over whether black Americans fighting for inclusion and enlisting in the military to defend their nation’s overseas interests should insist on a separate anthem—Johnson, himself, preferred to call his song the national negro hymn. But there’s “no evidence,” Perry says, that black communities at large were “ambivalent” about the song.

During World War II, in fact, black servicemen, still in segregated units, sang “Lift” alongside the national anthem at sporting events and other formal assemblies on their bases, says Robert Jefferson, an expert on black military history at the University of New Mexico. “During the first half of the 20th century, that song is revered by the black American military.”

The popularity of “Lift” waxed and waned over the years—it was usurped during the civil rights era by songs such as “We Shall Overcome” and “We Shall Not Be Moved.” But in the 1970s, amid the Black Power movement, it was sometimes sung with an air of resistance. “People are singing the song with raised fists, dashikis, afros,” says Perry, and black students at newly integrated schools fought to keep it in public school programs alongside the national anthem.

Indeed, the opening up of white spaces to African Americans has contributed to the song’s decline. Following the gains of the Civil Rights movement, black people participated less in civic groups that sang the song in their rituals, Perry says. In 1985—roughly 20 years after Congress passed a law mandating the integration of public schools—an Ohio State University sociologist found that about one-third of black college students could no longer identify “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” By that time, enrollment at black colleges and universities had dropped profoundly from their historic highs under Jim Crow. “It is inconceivable,” the researcher wrote, “that African-American college students of even a decade ago would have responded in this fashion.”

The spaces where black people hear “Lift” today are few and far between. We sometimes sing it in church, as I did growing up on the Southside of Chicago. It still can be heard at Black History Month programs and at formal gatherings of civil rights organizations like the NAACP and the National Urban League, and, of course, at HBCUs like my alma mater. But even HBCU students, decades removed from the song’s heyday, don’t necessarily feel connected to “Lift” in the way our grandparents or even our parents were, if my fellow Howard students and I were any indication. Few of us could sing past the first verse. My performance of it was usually pretty perfunctory. It wasn’t until recently that I really thought about the words and discovered how much they resonated with me.

Buried in the history of black people’s storied affair with “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a lesson on why we feel differently from white Americans about the NFL players who kneel during the national anthem: Because our relationship with the nation has been so fraught, black people have long felt ambivalent about the symbols and rituals of white America—which is why “Lift,” written for us, by us, exists in the first place. Black folks are compelled to tell our stories on our own terms, and for us the story has been one of unceasing struggle and protest. How fitting, then, that we would use America’s symbols to ink ourselves into its narrative.

Top image credit: National Archives and Records Administration; Jose Luis Magana/AP; Jane Kelly/Getty