Getty

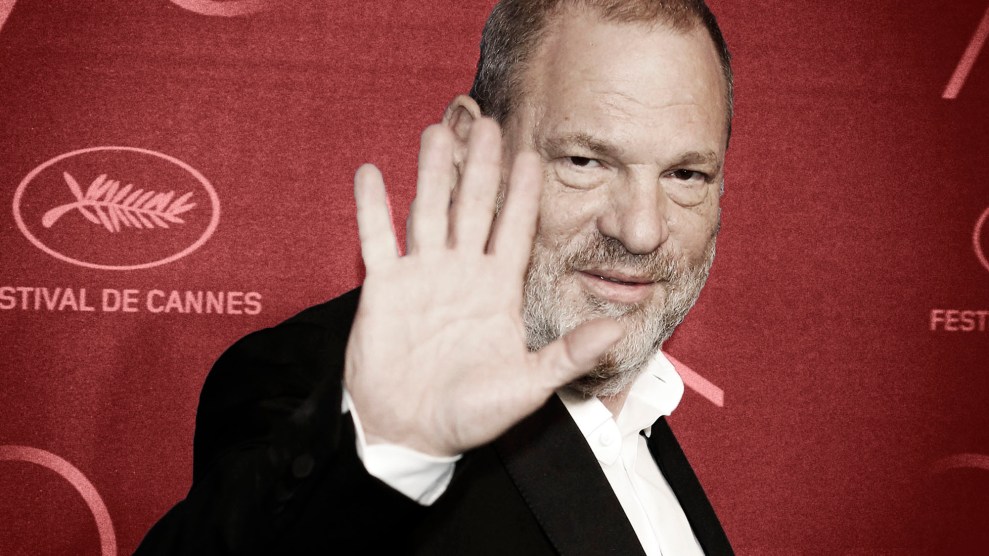

As the Harvey Weinstein scandal continues to grow, it’s become clear that strict language in various contracts limiting what employees and accusers could say was crucial in enabling the movie producer to get away with decades of alleged sexual harassment and abuse. As the recent New Yorker exposé details:

For more than twenty years, Weinstein, who is now sixty-five, has also been trailed by rumors of sexual harassment and assault. His behavior has been an open secret to many in Hollywood and beyond, but previous attempts by many publications, including The New Yorker, to investigate and publish the story over the years fell short of the demands of journalistic evidence. Too few people were willing to speak, much less allow a reporter to use their names, and Weinstein and his associates used nondisclosure agreements, payoffs, and legal threats to suppress their accounts.

Now lawmakers in New York state are targeting nondisclosure agreements that are often included in employment contracts and settlement deals, similar to the many that Weinstein struck with his accusers in which they agreed to silence in exchange for financial compensation. The proposed legislation is in some ways an extension of “sunshine laws” on the books in many states, which allow people to break confidentiality agreements in instances where there’s a public hazard.

State Senator Brad Hoylman (D) first introduced a bill in May that would make nondisclosure agreements prohibiting employees from speaking out against harassment and discrimination unenforceable. More specifically, the legislation would prohibit employers from asking their employees waive their rights related to claims of “discrimination, non-payment of wages or benefits, retaliation [or] harassment.”

After the Weinstein scandal broke, Hoylman decided to add language to the bill that would prohibit nondisclosure clauses in contracts and agreements that are the result of any sort of complaint that violates the law. A draft of the amendment shared with Mother Jones reads: “A provision in any contract or agreement which has the purpose or effect of concealing the details relating to a claim of discrimination, non-payment of wages or benefits, retaliation, harassment or violation of public policy in employment, including claims that are submitted to arbitration, shall be deemed unconscionable, void and unenforceable.”

“No longer will nondisclosure valve be a safety valve for bad behavior,” Hoylman tells Mother Jones. “It’s time that employers took responsibility and cleaned up their workplace. These types of agreements perpetuate numerous examples of harassment and unprofessional and illegal conduct in the workplace…and it’s something we need to consider as a state and quite frankly a society whether we’re going to allow employers to get away with this kind of stuff.”

Hoylman first introduced the legislation with Gretchen Carlson’s accusations of sexual harassment against Roger Ailes in mind. “I think there are numerous examples in the media that will hopefully help motivate my colleagues into moving this legislation,” he said.

The General Assembly session doesn’t start until January, so it will be awhile before the legislation can move forward, but it’s already gaining a little momentum from state lawmaker Nily Rozic (D), who plans to sponsor it in the General Assembly. “It’s an important aspect that we address so young women who are starting in their careers or who are well-established in their careers can feel like they can have productive, professional lives without retribution or fear of this economic pressure that employers often seek,” she says in an interview with Mother Jones.

Professor L. Camille Hébert, a law professor at the Ohio State University Moritz College of Law with expertise in discrimination and sexual harassment in the workplace, has seen that economic pressure first hand, noting that sometimes victims of harassment are sued for speaking out and breaking nondisclosure agreements.

Still, she says this kind of legislation won’t be a silver bullet. There could be some drawbacks even, since companies know how difficult it is to win sexual harassment lawsuits. She explains that “companies might be less willing to settle if they aren’t able to get a nondisclosure agreement,” which could result in lower settlements or could force accusers to bring their case to trial. On top of that, coming forward still unfortunately carries the risk of damaging one’s career, she notes.

Even so, Hébert thinks the benefits of getting rid of nondisclosure agreements significantly outweigh the disadvantages. “What allows the pattern to continue is people settle things quietly and then no one can talk about them,” she says. In other words, while some individuals could lose out financially, those who have been harassed will have more power to speak out and it’ll be harder for harassers to get away with such behavior. “It might make it harder to get a settlement without suing,” she says. “On the other hand, my view is women don’t really want lawsuits. Women want not to be harassed.”

Assemblywoman Rozic agrees and explains those concerns were considered in developing the legislation. “Overall, the larger issue outweighs whatever smaller concern people might have about the size or the publicity around the settlement,” she says.

While Hébert sees the New York proposal as a positive step forward, she warns that legal efforts to curb harassment can only do so much. “The best way to deal with sexual harassment effectively is to deal with it as it arises, making it clear it’s unacceptable,” she says, noting that waiting until sexual harassment becomes public and giving the accused a $40 million severance package, such as in the case of Roger Ailes, sends the message that such behavior is tolerated.