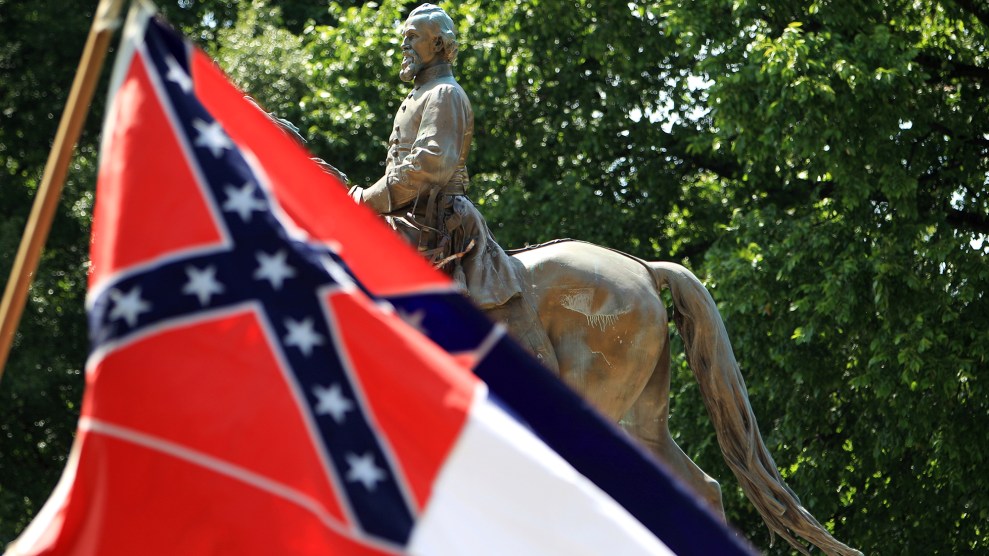

A Mississippi state flag waves in front of the statue and tomb of Nathan Bedford Forrest, rebel general, slave trader and early Ku Klux Klan member.Mike Brown/Commercial Appeal via AP

On Monday, Mother Jones published an essay by Nate DiMeo chronicling the history of a hotly-debated Confederate monument in a park in downtown Memphis, Tenn. Last week, the effort to remove the statue was blocked again.

Memphis city officials and activists have been working for two years to get rid of the monument, of Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest, along with a statue of Jefferson Davis that stands in another park. The Tennessee Historical Commission was scheduled to vote on an application from the city council to remove the Forrest statue on Oct. 13, but the vote has been delayed—possibly until February 2018. (The removal of the Jefferson Davis statue is a lower priority for the city council right now since a hearing on it probably will not happen until next year.)

On Thursday, the Commission chairman sent a letter to the city attorney informing him that the historical commission’s vote would be delayed pending the approval of a new set of rules governing applications for waivers that are submitted to the commission.

Memphis residents were frustrated by the delay. “Most of this community, the vast majority of Memphis, wants these statues down but wants to do it legally,” Mayor Jim Strickland said in a recent interview with local TV station WREG. “When I was on the city council, we voted to take these down, that’s like three or four years ago. It’s time for a decision.”

The council is also losing patience with the commission. Early last month, city council members voted to sponsor an ordinance to override the commission and remove the Forrest statue from its current spot “to a more suitable location” such as Savannah, Tenn. or a Civil War Battlefield site in Mississippi. Forrest and his wife are also interred beneath the statue, and their bodies would be reburied in their original resting place in Elmwood Cemetery.

Allan Wade, the city council attorney, said the city could argue that Confederate statues keep African American people from accessing the parks, which would grant protection under a Supreme Court ruling guaranteeing equal access to parks regardless of race.

This is the latest move in a years-long battle between the Commission and the city that has intensified in the past few months in the wake of the Charlottesville protests. The city council first voted to remove the statue of Forrest in 2015, after a shooting at a historically-black church in Charleston, S.C. left nine dead.

It may seem strange that the Tennessee Historical Commission—a group formed under the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation that includes Gov. Bill Haslam and the State Historian—can overrule a city council vote. The Commission was granted that power by a state law known as the Heritage Protection Act passed in 2013 and amended last year designed to protect state memorials to the Confederacy.

Last year’s amendment made that rule more ironclad: Now a waiver can only be awarded in cases where two-thirds of the commission’s 29 members approve. The law, the Nashville Scene recently noted, was written partly by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a group made up of “living descendants of the soldiers and civil servants of the Confederate States of America,” according to their website. The group says it has a “covenanted responsibility to preserve the Christian principles held by the Southern people which led to their decision to defend constitutional self-government” and its mission is “to preserve the memory and the good name of the noble soldiers, civil servants, and loyal citizens of the Confederate States of America, and the cause for which they fought and died.” Some members of the historical commission also belong to the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

City Attorney Bruce McMullen said back in August that he expected the commission to reject the city’s request for a waiver, and pledged to sue all the way up to the state’s Supreme Court if that was the case. If that happens, removal of the Nathan Bedford Forrest statue could take years.

According to a report from the Memphis Police Department, keeping the statue in the park has come at a high price for taxpayers. The overtime pay alone for monitoring four rallies August 15-28 cost the city $16,530, on top of $8,795 for typical patrolling at the parks during that time.

The removal of the statue and the accompanying graves is widely supported in Memphis, a city with a long history of civil rights activism and a majority-black population.

In a Facebook post Friday, the Memphis chapter of Sons of Confederate Veterans said they had “prayed hard” about the Forrest statue, and they were “pleased” with the Tennessee Historical Commission’s actions.

Read Nate DiMeo’s essay on the history of the statue here.