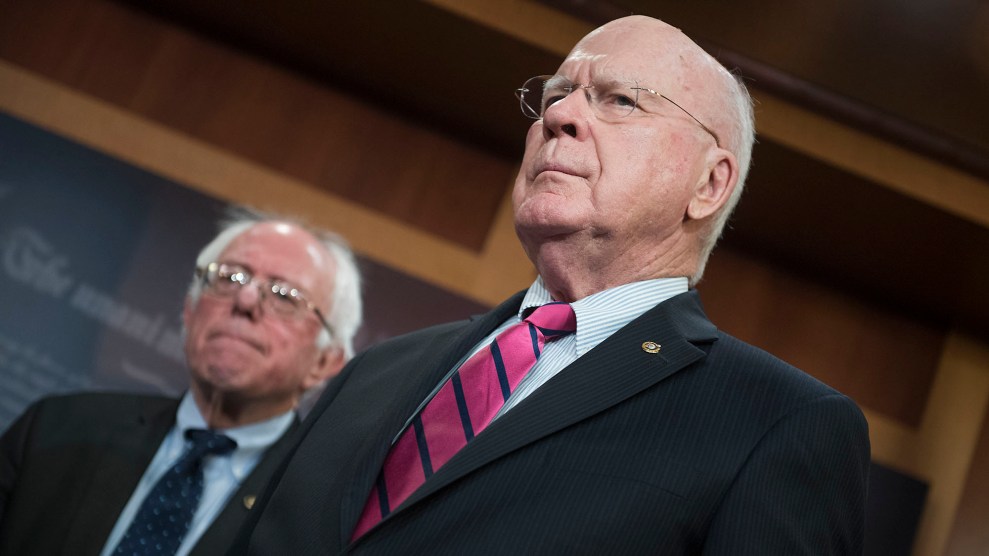

Jim Loscalzo/DPA via ZUMA Press

In 2013, the Senate voted on whether to reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act, a 1994 law that aids victims of domestic and sexual violence. In previous years, the law had been reauthorized without difficulty, but this time was different, sparking a year of debates in Congress over a set of additional protections introduced by Democrats. Still, when the measure returned to the Senate for a final vote, the result was overwhelming: 78 senators voted in favor, and just 22 were opposed. In the latter camp was Jeff Sessions, an Alabama Republican who had told CNN, “Fundamentally, you can’t vote [for] a piece of legislation you don’t think is sound.”

Four years later, Sessions has been confirmed as attorney general, putting him in charge of carrying out the same version of the Violence Against Women Act that he opposed. That has advocates for victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking worried that Sessions could oversee a shift in enforcement that will leave victims vulnerable.

During his time in the Senate, Sessions voted twice—first in 2000 and again in 2005—in favor of reauthorizing the Violence Against Women Act, known as VAWA. Both reauthorizations passed unanimously. But when the law came up for review in 2012, it contained several significant additions: an increase in the number of visas available to battered immigrant women fleeing their abusers, new nondiscrimination protections for LGBT survivors of violence, and a provision granting tribal courts the authority to prosecute non-Native Americans who abused Native women on tribal land.

Senate Republicans argued that the new provisions were too broad and would invite abuse of VAWA funding. Sessions accused Democrats of including them to turn the reauthorization into a political battle. “There are matters put on that bill that almost seem to invite opposition,” he told the New York Times in 2012. “You think that’s possible? You think they might have put things in there we couldn’t support that maybe then they could accuse you of not being supportive of fighting violence against women?”

Sessions’ opposition to the expanded VAWA has some advocates worried that his Justice Department will not prioritize protections for victims—particularly victims who belong to marginalized groups, given Sessions’ longstanding hardline conservative views on immigration, LGBT equality, and civil rights issues.

“When you think about what a [Department of Justice] should be, the role that a DOJ can play, and juxtapose that with the record that Sen. Sessions has had historically with regards to civil rights, with regards to women’s rights, it is clear to us that he should not [have been] confirmed to a position that is as crucial as this position is,” says Fatima Goss Graves, a senior vice president at the National Women’s Law Center, which examines how policies affect women.

Sessions’ record offers little reassurance that he would work actively to help marginalized communities. He has voted against other measures that aim to protect some of the same groups covered by VAWA. LGBT groups are especially concerned, noting that Sessions supported a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage and ardently opposed a 2009 hate crimes bill that expanded protections for LGBT people and rape victims. One day after Sessions assumed office, the Justice Department withdrew its legal defense of an Obama-era directive protecting transgender children in schools.

“The Violence Against Women Act is currently the only law that includes explicit protections around sexual orientation and gender identity,” says Emily Waters, senior manager of national research and policy for the New York Anti-Violence Project, which provides services for LGBT victims of violence. “Without an attorney general who is willing to put resources behind that, a lot of the nondiscrimination protections lose a lot of their impact.”

Sessions’ previous opposition to increasing VAWA protections for immigrant women suggests he’s unlikely to consider domestic violence when helping implement Trump’s recent executive order calling for increased deportations. Earlier this month in El Paso, Texas, a transgender victim of domestic abuse appeared in court to seek a restraining order against her assailant. While in the courtroom, she was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement after it was revealed that she was undocumented. Early reports suggested that her abuser tipped authorities off to her immigration status.

Stories like this suggest that undocumented victims might be less protected under a Sessions Justice Department that is likely to crack down on undocumented immigrants. “What we know from experience is that when an immigrant community knows that local law enforcement is regularly collaborating with ICE, victims are not going to come forward,” says Grace Huang, policy director of the Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence and a member of the National Task Force to End Sexual and Domestic Violence. “They are going to stay in the shadows. And that harms all of us.”

She adds, “We’re probably going to have to change our advice to survivors on how to stay safe.”

Last October, Sessions was asked about the controversial 2005 Access Hollywood video that showed Trump bragging about grabbing women’s genitals without their consent. “I don’t characterize that as sexual assault,” he told the Weekly Standard. “I think that’s a stretch.” He later said his comments were mischaracterized. During his confirmation hearing last month, Sessions said that if a woman were grabbed without her consent, “clearly it would be” sexual assault.

Lisalyn Jacobs, a former Justice Department staffer during the Clinton administration, says the incident illustrates not only Sessions’ poor understanding of assault but also his willingness to defend Trump in any situation. “[Sessions] may have been hired by Donald Trump to do that job, but Donald Trump is not his client,” says Jacobs, who is also a member of the National Task Force to End Sexual and Domestic Violence.

Sessions has been silent on his plans for the Justice Department’s Office on Violence Against Women, which is responsible for enforcing VAWA and funding services for victims. But a blueprint from the Heritage Foundation—a powerful conservative group with close ties to the Trump team—calls for eliminating all Violence Against Women grants. The blueprint was widely circulated last month and is reportedly being used as a guide for the administration, reinforcing advocates’ concerns about the future of many VAWA programs.

“If you care about violence against LGBTQ people, against communities of color, against immigrant communities, [you] should really, really be paying attention to Jeff Sessions,” says Waters. “We really have to continue to watch him and never pretend that he is going to be an advocate for marginalized communities.”