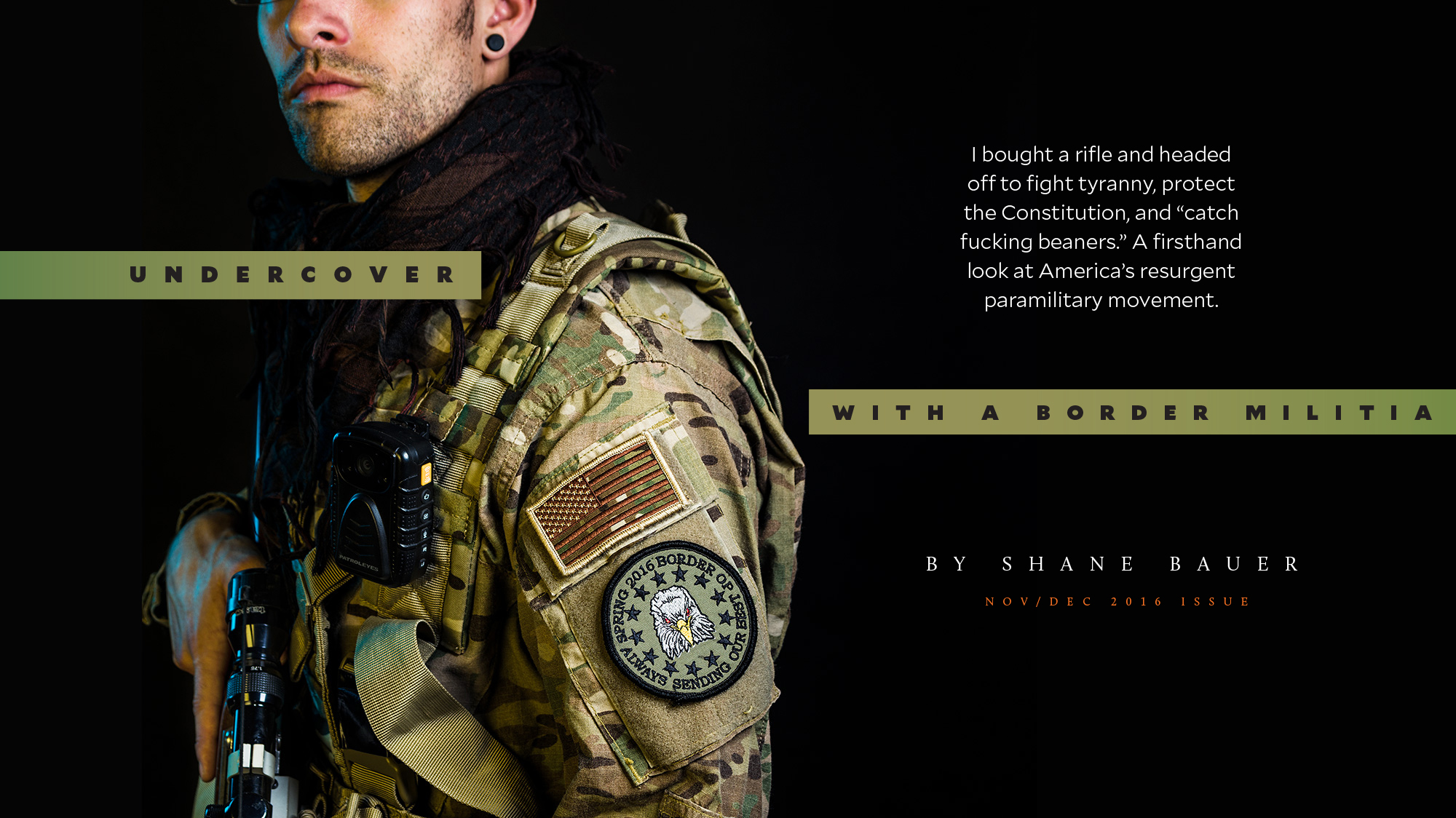

I crawl out of the back of the pickup with my rifle in hand. “Keep your weapons nice and tight,” Captain Pain orders. I am traveling light. Unlike the others, I don’t view southern Arizona as a war zone, so I didn’t put steel plates in my chest rig. Next to everyone else’s commando-style AR-15s, my Ruger Mini-14 with a wood stock is slightly out of place. But everything else is square—I’m wearing a MultiCam uniform, desert tan combat boots, and a radio on my shoulder. I fit in just fine.

We are in a Walmart parking lot in Nogales. Captain Pain and a couple of others go into the store to get supplies. In Pain’s absence, Showtime is our commanding officer. He is a Marine special-ops veteran who did three tours in Afghanistan. He has camo paint on his face and a yeti beard. He gets in the cab to check Facebook on his phone while Destroyer, Jaeger, Spartan, and I stand with our backs to the truck, rifles in hand, keeping watch for anything suspicious. The Mexican border is three miles away.

“There you go,” Jaeger says, looking across the lot. “Camaro with rims.” His hands rest casually on the butt of his camouflage AR-15, which hangs over his chest from a three-point tactical sling.

“You know every other Mexican has chrome rims on his car,” Destroyer says in a reasoned tone, suggesting that this particular ride might not belong to a drug cartel. He’s clutching the pistol grip of his AK-47, his trigger finger responsibly pointed down the receiver.

“Last time we were here, [there was] a blacked-out car,” Spartan adds. “Big-ass rims on it. Bumping Mexican music. It cruised us twice. Slowly, too.” He spits out a sunflower seed.

Destroyer nods toward the parking lot entrance. “Here comes the sheriff,” he says. A cop car is pulling into the lot.

“He’s looking at us,” Jaeger says.

“Of course he is,” Destroyer says.

“Keep your hands out!” a man in a dress shirt suddenly yells from the row of cars across from us. “Police!” His hand is hovering over his sidearm. The guys I’m with hold their hands out at their sides. Their rifles dangle over their chests. I don’t have a tactical sling, so my rifle is still in my hand.

“Put your weapon down!” another plainclothes cop shouts at me. I bend down slowly and put my rifle on the ground.

The police approach us. “You guys hunters or what?”

“Militia,” Jaeger replies.

“You guys have IDs?” I reach for mine. “Keep your hands out of your pocket, please!” one barks.

Two cop cars pull up and three uniformed officers from the Nogales Police Department get out. “What are you guys doing down here exactly?” a cop asks. Her name tag reads “Hernandez” and she has short, spiky black hair.

“We’re just being the eyes and ears of the Border Patrol, basically,” Jaeger says.

“Somebody probably saw guys with long rifles and camouflage and thought, ‘Holy crap!'” another officer says.

“Scary-lookin’ bunch,” Destroyer says as he picks at his teeth in a slightly forced pose of calm.

“Nah, you guys aren’t scary,” Officer Hernandez says. “I guess people just aren’t really used to seeing a group out practicing their right to bear their arms, and they freak out if they do. No worries.” She radios in our IDs and then asks how we ended up in Arizona.

“Well, back in Colorado we are part of a patriot organization,” Jaeger says. “Three Percent United Patriots.”

“So do you guys get like deployed and come for days at a time, or…?”

“Yeah,” Jaeger says. “Our CO has the final say in who comes and who doesn’t.”

“It takes balls to do what you guys do out there,” Hernandez says. “Thank you.” She gives us back our IDs. The cops get in their cars and leave.

Destroyer looks at me. “Is your camera rolling?” I am wearing a body cam on my chest rig.

“Yeah,” I say.

“Smart man,” he says approvingly.

“You’re gonna have to post that,” Jaeger says.

Ready for the Worst

Captain Pain takes us back to the FOB—forward operating base—a one-hour drive down a rugged dirt road that winds over the Patagonia Mountains. Destroyer says that was the best interaction he’s ever had with cops. “Moral of the story: Come fully armed to a police encounter,” he says. Jaeger is surprised how friendly Officer Hernandez was, given her name. He points out that her hair was shorter than all of ours; Destroyer refers to her as “it.” “How many feminists does it take to screw in a lightbulb?” he asks. “Twenty. One to screw it in and 19 to whine about how men should do it.”

“How do you tell a Jew from a Slav?” Jaeger says. “You can’t. They’re both ashes. Hahaha!” Jaeger’s parents are German immigrants. He has dual citizenship, and he’s conspicuously proud of his heritage. Some guys call him a Nazi, neither approvingly nor disapprovingly, but in a boys-will-be-boys sort of way.

Spartan, who is a Transportation Security Administration agent, laughs along with the stream of jokes but doesn’t say much. Whatever emotions he has are stowed away behind wraparound shades, a thick red beard, and the Middle Eastern keffiyeh that’s often draped over his head. Stoicism is expected here, so the fact that I rarely speak doesn’t draw attention. I don’t lie to the guys, but I don’t tell them I’m a journalist either. I can tell them about my background in the militia movement: Before joining the Three Percent United Patriots (3UP) for this border operation, I trained with the California State Militia and the 31st Defense Legion across northern and central California. I learned marksmanship, land navigation, patrolling skills, rappelling, radio communication, code language, how to set up an FOB in a hostile situation, and how to hold defensive positions. Like the other guys, I adopt a call sign to protect my identity. In California, some knew me as Rattlesnake. Here, they call me Cali.

Becoming a militia member began with opening a new Facebook account. I used my real name, but the only personal information I divulged on my profile was that I was married and that I had held jobs as a welder and a prison guard for the Corrections Corporation of America. A “Don’t Tread on Me” flag was my avatar. I found and “liked” militia pages: Three Percenter Nation, Patriotic Warriors, Arizona State Militia. Then Facebook generated endless suggestions of other militia pages, and I “liked” those too. To keep my page active, I shared other people’s posts: blogs about President Barack Obama trying to declare martial law, and threats of Syrians crossing the border. I posted memes about American flags and police lives mattering. Then I sent dozens of friend requests to people who belonged to militia-related Facebook groups. Some were suspicious of me: “Kinda have a veg profile, so I got to ask why you want to be my friend????” one messaged. Many, however, accepted my friend requests automatically. Within a couple of days, I had more than 100 friends, and virtually any militia member who looked at my page would likely find that we had at least one friend in common.

Then I came across the Three Percent United Patriots’ private “Operation Spring Break” Facebook group. I requested access, and when it was granted I saw a post asking who was coming to the operation in April. I replied, “Yes.” The purpose of the operation wasn’t posted anywhere because it was understood implicitly—to catch illegal immigrants and drug smugglers. Eventually, the coordinates for the forward operating base inside Arizona’s San Rafael Ranch State Park were posted. No one asked me anything about myself. All I had to do was show up. The list of required equipment was extensive, including weapons, medical supplies, and body cameras. The idea was that video footage would disprove anyone making false accusations against the militiamen. I used my body cam to capture what I saw and heard. No one raised an eyebrow.

Members of 3UP view their border operations as an opportunity to serve the nation while putting their training to the test and honing their skills for the battle to come. Like most militiamen, they believe societal collapse is imminent. There are many theories about what will make the “Shit Hit The Fan.” Some believe it will be economic collapse. It could be civil unrest provoked by Black Lives Matter. It could be a natural disaster. It could be a government attempt to disarm gun owners and impose martial law. While many in the broader “patriot” movement prepare for that day to arrive, members of 3UP see themselves as men of action, sheepdogs in a nation of blind, ignorant sheep.

As we approach the FOB on our way back from Walmart, Captain Pain radios in our arrival. This is protocol for anyone coming or going. Two men are patrolling the perimeter with AR-15s, and if we don’t announce ourselves, they might mistake us for bad guys. These are not the only security measures: I’m told there are motion sensors in the dry riverbed that flanks the base, men sometimes take positions on surrounding hilltops, and most meals are prepared with bacon grease or pork to keep would-be Muslim infiltrators at bay.

The best way to understand America’s paramilitary movement is to go deep inside it. Help fund investigations like this with a tax-deductible donation to MoJo.

It’s midday and men are sitting around playing cards, staring at empty fire pits, and napping in their tents. More than 40 people have come here from Arizona, Colorado, Texas, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and other states. Almost all are white, but there are one or two Latinos. They are roofers, electricians, heavy-equipment operators, welders, a prison nurse, and a bounty hunter. Most of the men are militia infantry like me, but others have more specialized roles. Blackfin controls shortwave radio communications from a camper with a tall antenna sticking out of its roof and a generator humming at its side. A man from Oregon cooks breakfast and dinner under a large kitchen tent. The camp medic, Rogue, sits under the medical tent, staring into his cellphone. Some of the men grumble about a local TV news crew from Alabama that’s filming around the base and nearly foiled one of the nighttime ops by switching on a light near the border fence.

A modified American flag hangs motionless from a gnarled mesquite tree, its canton of 50 stars replaced with a Roman numeral III surrounded by 13 stars. It’s the standard of the three percenters, symbolizing their foundational belief that just 3 percent of American colonists were responsible for overthrowing the British in the Revolutionary War, and that it will take 3 percent of today’s Americans to bring about the “restoration of the Founders’ Republic.” The idea originated in 2008 with Mike Vanderboegh, a former militia member and far-right-wing blogger who died in August. Vanderboegh said three percenters were “willing to fight, die and, if forced by any would-be oppressor, to kill” to defend the Constitution.

The three percenter philosophy has quickly grown into a grassroots, national movement, part of a resurgence of right-wing militia activity following Obama’s election in 2008. An Amazon search turns up more than 4,000 results, ranging from baby clothes to iPhone cases with the three percenter logo. There are more than 300 three-percenter Facebook pages, websites, and discussion forums. The main 3UP Facebook group has more than 15,000 members, though the actual number of people who belong to active real-life “threeper” groups is difficult to estimate.

A Marine veteran and IT manager from Colorado named Mike Morris, known here as Fifty Cal, felt that if threepers were going to restore the Constitution, they needed to be organized and well trained. In 2013, he founded 3UP and became its commanding officer. Membership “exploded” after the Ferguson protests, he says. He boasts that the 3UP’s Colorado branch, its largest, now has 3,400 members.

We don’t see Fifty Cal much; mostly he stays holed up in a Kodiak trailer at the far end of camp, planning day and nighttime operations, consulting with officers, and watching war movies. This is the eighth and largest national border op he’s organized since 2014. He doesn’t think 3UP is going to stop drug smuggling or illegal immigration with these operations, but he feels they are a chance for patriots to serve their country. He doesn’t even think immigration is the main concern. The real problem is that America has become unrecognizable: The federal government has become tyrannical and the country’s customs and culture are being destroyed. “We lose more and more rights, more and more freedom, every day,” Fifty Cal told me when I called him after the border op. (I attempted to contact all the militia members mentioned in this article. A few agreed to talk on the record.) He said 3UP isn’t “all about guns and camo.” It has done relief work in response to the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, and floods in Louisiana and South Carolina. It has donated food and clothes to veterans. “3UP itself is not necessarily a militia,” Fifty Cal told the site AmmoLand.com. “We are more like the close cousin of the militia, maybe militia evolved.”

Fifty Cal steps out of his trailer and hacks a phlegmy smoker’s cough. A green and white Border Patrol SUV rolls into camp and a portly, smiling white man in a green uniform steps out. Fifty Cal is not smiling, and I am nervous. Most of the men sitting around the base aren’t carrying their rifles, but they are wearing sidearms. Fifty Cal runs his hand down his long, red goatee. His belly bulges through a black T-shirt that says “ISIS Hunting Permit” over an image of a skull. He drags on his cigarette, revealing his tattoo-sleeved arms.

“What’s up, my friend?” the agent says. Fifty Cal opens his arms and the two embrace, slapping each other’s backs. Fifty Cal grins.

“Good to see you, man,” he says. “How you been?”

“Just trying to get by, man. You know how it is.” The agent’s name is Mike. Guys stand around and chat with him like old buddies. Mike tells us stories about drunk teenagers who have been overturning vehicles, and about Border Patrol motion sensors capturing pictures of an old man who hikes naked. Mike has worked in this area for 10 years, and the guys try to glean tips from him on how to spot Mexicans sneaking through the desert. Mike says he likes his job. “This is a combat deployment that I get to go home every day and sleep in my own bed. I get all the action, but I don’t have to go packing bags.”

Fifty Cal and his executive officer, Ghost, walk with Mike over to his vehicle, where they talk for a while. After Mike leaves, Ghost marches through the camp. He walks like a drill sergeant and looks like a construction worker, his build sinewy and his skin deeply tanned. “Who took a picture of the Border Patrol agent?” he asks. People shake their heads. Someone says Sandstone had a camera out. Ghost goes to find him. “We don’t take photo ops with the Border Patrol,” one man says.

Ghost comes off as an enforcer, but really he is a man of the people. While Fifty Cal sequesters himself in his trailer, Ghost sits around the fire with his men. He doesn’t say much about politics, but on his Facebook page he writes that Hillary Clinton is a “bitch” who “needs to hang from a tall tree until dead dead dead.” A lot of the guys don’t like either party. “Each of ’em is as corrupt as the other nowadays,” Fifty Cal says. Jaeger says he’ll be voting for Gary Johnson, the Libertarian candidate. Ghost, however, supports Donald Trump. He tells us he’s worried about the day when ISIS integrates with the cartels and starts hopping over the four-foot border fence just south of here. Until Trump is president, Ghost says, we are the wall.

The guys just can’t believe how many Muslims there are in the country today. “Saudi fucking Aurora is what it is,” Captain Pain says of his hometown in Colorado. “We need to kill more of those motherfuckers. I never seen so many fucking towelheads stateside.”

“I remember when the part of Aurora I lived in was just white people,” Jaeger says.

Like Fifty Cal, Ghost laments how much the country is changing. People like him with an honest trade used to be comfortable. And he didn’t hear people complaining about white men all the time like they do now. Everyone’s become so uptight. It wasn’t like that when he was young, living in Los Angeles, cruising up Hollywood Boulevard with his buddies. “We’d fuck with the hookers,” hanging a $20 bill out the window and watching them chase the car. “Actually, there were some damn good-looking hookers compared to East Aurora. Big old fat nigger wandering around: ‘Come here, baby!'” he shouts mockingly. “No! Get the fuck back! There ain’t enough booze in the world, woman.” He lets the N-word slip sometimes, even though it seems to make some of the guys a little uncomfortable. Fifty Cal later told me that racism isn’t tolerated and that “We have removed and blocked folks that didn’t align with our ideals.” In its official communications, 3UP insists it is not a white supremacist organization. No one ever speaks up at this kind of language, though. To show offense would be to give in to political correctness, which is a step toward Big Brother mind control.

Ghost says America’s sense of history has gone down an “Orwellian memory hole.” Who remembers Randy Weaver anymore? Ghost was 25 years old in 1991, when Weaver, a member of the white supremacist Christian Identity movement who’d been charged with selling sawed-off shotguns, holed up with his family in their cabin in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, for 18 months. A shootout ensued, and a federal deputy and Weaver’s 13-year-old son were killed. During the 10-day siege that followed, an FBI sniper killed Weaver’s wife as she held their baby. Ghost is convinced that Weaver’s real crime was distrusting the government.

To Ghost and other patriots, Ruby Ridge remains a sign that the government is willing to go to war against its citizens. A year after Ruby Ridge came the siege of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, where cultists had been stockpiling weapons and more than 1 million rounds of ammunition. The FBI eventually assaulted the compound, resulting in a blaze that killed more than 70 men, women, and children. The rumor that the feds intentionally set the fire persists among far-right groups and conspiracy peddlers like Alex Jones. The 1994 federal assault weapons ban solidified patriots’ belief that Washington was making final preparations to turn America into a totalitarian state. By the mid-’90s, hundreds of paramilitary groups had formed across the country, styling themselves as “militias” to invoke the volunteers who’d fought in the American Revolution.

The 1995 Oklahoma City bombing sparked a backlash against the anti-government extremism that had spawned Timothy McVeigh. The militia movement effectively went dormant following the election of George W. Bush in 2000. Then came the first black president. In the three years after Obama took office, the number of active militias in the United States increased eightfold, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. By 2015, there were more than 275 groups in at least 41 states.

The movement is bound together by a shared disdain for the federal government, but individual members’ motivations for joining can vary widely. “We all have different reasons to be here,” Captain Clyde Massengale of the California State Militia’s Delta Company told the new recruits at my first training. “Some might believe what is happening is something biblical right now. Some might believe it’s the New World Order. Some might believe the New World Order is making what is happening follow the Bible. Who the fuck knows? Who the fuck cares?” Come what may, the militia would be ready. When shit hit the fan, it would have a secret, fortified bugout location where we could bring our families. A new community might someday need to be built there. Massengale said that under his command, life in the bugout would be modeled after ancient Rome. Active, patched members of the California State Militia would be considered citizens, while lapsed members and outsiders would not. “We need worker bees,” he said. “You wanna come in? We’ll bring you in. You’ll be down in the field growing food, gathering wood. We’ll be the ones standing watch,” he said. Then he added in a loud whisper, “In the houses, not in the tents. Hahahaha!”

I looked to the one black man in the group, a recruit who had family near the mass shooting in San Bernardino a week earlier. “I hate to tell you, but I’m in for the long count,” he told the captain. “So you’ll be seeing my black ass here every time.”

The captain responded that in his experience, black people were always the best at learning and executing orders. “We need to see some more black asses, is what we need,” he said. Another man added, “We need diversity.”

Walking the Line

For the afternoon op, Ghost pairs me with Doc, a deep-voiced 55-year-old welder from North Carolina. We climb into Ghost’s truck, The Moose, and he asks me how much ammo I have on me. About 50 rounds, I tell him. He has 200. “I’ll probably never need all that,” he says. “However, we get out there, say we catch a group of about six or seven going south—” He suddenly stiffens to strike a pose. Sandstone is taking a picture of us. Doc tells him to send it to him on Facebook.

We drive in a three-truck convoy for about 45 minutes, down long dirt roads flanked by expanses of tall, dry grass and scattered mesquite trees. “Three hundred twenty-three dollars for a flight to Tucson and back,” Doc shouts to me as the wind whips our faces. “One hundred forty dollars for meals. The feeling that you’re doing something for everybody else in the country: priceless.” The mountains that shelter the base grow small in the distance. “Yee-haw!” Doc shouts. “Rock and roll!”

When we pass through a near-empty border town, Doc points out a ranch. “These fuckers are in bed with the cartel if they don’t belong to it. You can kinda tell by just how trashy it is. It’s not well maintained. If they’re ranching, where’s all the fucking cattle?”

The family is Latino. “They don’t like us at all,” Doc tells me. “You catch on fire, don’t expect us to piss on you to put you out.” I’ve heard mention of this ranch several times. Fifty Cal said that every time they come to Arizona, they sit on top of a nearby hill and watch the people coming and going from it.

I ask Doc whether any of them have ever spoken to the rancher.

“Nah, I never even seen him out myself.”

Ghost drops Doc and me off on the road and tells us to patrol the ravine and look out from the ridge above for the next several hours. Doc says he’s glad I have a body camera, just in case.

“What made you sign up?” I ask Doc as we walk along the high slope of the ravine.

“I saw the way this country was headed,” he says. “I started giving up on the sheep. Sheep don’t wake up. They’re sheep. You ain’t gonna turn a sheep into a sheepdog. You can only find the sheepdogs that are out there.”

He says everything changed for him after Obama was elected. “I see a time comin’ when there will be blue hats patrolling our streets.” He is referring to blue-helmeted UN troops. “‘Cuz he wants to make the world government. He wants to subject the US to international law and submissiveness. UN control. World government control. Just to make the US another satellite nation. Do away with sovereignty.”

We sit in the shade of a tree. Doc leans against his backpack and rests the muzzle of his AR-15 on his knee, pointing straight ahead. He says he bought his first semi-automatic rifle once he realized what Obama was doing. “My goal was, as soon as the blue helmets hit the shore, to kiss my wife goodbye and do the best I can. I’d find the blue helmets and start killin’ ’em as fast as I can until they get me.”

Lots of militiamen worry about a UN invasion, but Doc worries the invaders won’t actually be wearing blue helmets: They might be undercover. Take the standoff earlier this year, when a bunch of armed patriots occupied the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in eastern Oregon to protest the federal government’s claim over public lands. Doc says there were police there with tactical gear and M4 rifles who wouldn’t tell people what agency they were with. “That ain’t the way this country works,” Doc says. “A law enforcement officer has to identify himself to you.” They might have been UN troops. Or they could have been cartel.

When he first heard of the 3UP border operation, “I thought to myself, if I get a little bit of training, I might get more of them”—the blue helmets—”before they get me. Instead of getting 5 or 6, I might get 10 or 12. Or 20. Who knows? I’ve learned enough now that I might even get a couple dozen.”

The militia movement walks a delicate line between stoking its members’ paranoid fears and fantasies of rebellion and holding them in check. I remember the probing looks of militia recruiters in California when they asked why I wanted to join them. At a hushed meeting in a San Rafael Starbucks, an officer from the 31st Defense Legion simply told me, “No crazies and no anarchists.” It didn’t seem that they were testing my politics so much as wondering, “How close are you to snapping? Can you keep it under control?”

After the San Bernardino shootings, the California State Militia expelled a man because he was posting the prayer times of a mosque. One of its officers warned me they’d told the FBI about a prospective recruit who said he wanted to assassinate Gov. Jerry Brown. I later asked Massengale if he worried that one of his men could snap. He replied, “I worry every day that people who come into the militia will go out and do something.”

It’s as if many militia leaders know they are dealing with a pool of volatile white men, some of whom are convinced that society has screwed them and are at risk of exploding. For some, like Doc, the militia seems to rein them in by giving them a sense of purpose.

For others, the militia provides a justification for violent fantasies of insurrection. In 2010, a man in Idaho trained members of his militia to build bombs to fight off a communist invasion. The following year, the head of the Alaska Peacemakers Militia conspired to kill a judge and police officers. Also in 2011, members of a militia in Georgia planned to attack government buildings and random people with the deadly poison ricin, all to save the Constitution. In 2014, another group of Georgia militiamen planned to bomb federal facilities because they believed it would spark martial law and provoke a militia uprising. David Burgert, a Montana militia leader, shot at police officers shortly after being released from prison, where he’d served time for possessing illegal weapons as part of a conspiracy to assassinate cops and criminal justice officials to trigger a patriot revolution. He disappeared into the woods and remains at large. This October, three men belonging to a Kansas militia called the Crusaders were charged with domestic terrorism for allegedly plotting to bomb Somali immigrants on the day after the election.

And there was Forever Enduring, Always Ready (FEAR), a small Georgia militia consisting of active-duty soldiers who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2011, its leader, Isaac Aguigui, asphyxiated his pregnant wife to get her life insurance money. He then spent nearly $90,000 on guns and ammo for the militia. He intended to buy land for training militias in Washington state and to further fanciful plots such as poisoning the state’s apple supply, bombing a park, assassinating Obama, and ultimately overthrowing the government. When a teenage friend of Aguigui who was not a FEAR member heard about some of its plans, two militia members shot him and his girlfriend. Aguigui is now serving life in prison.

Doc walks down into the ravine and I walk along the ridge above it so that one of us can maintain radio contact with Ghost. When we meet back up, Doc looks at the yellowing horizon. “That’s a purty sunset,” he says. He suggests we trudge up the hill to get a good view. On the way, he points out a white desert flower, the distant mountains. The bottoms of the scattered clouds become a deep, fiery purple. “Oooooh baby!” Doc says. “Please can I get a shot of that?” He pulls out his flip phone and photographs the sunset, and we find a tree to sit under for the next couple of hours. We sit on opposite sides, taking turns scanning the horizon and the ravine with binoculars.

It becomes cold and dark. Doc offers me a piece of an apple-cinnamon-flavored survival bar as a treat. He bites into his chunk. “You ain’t got to eat that if you don’t want to, now,” he says bashfully. “Drier than mama’s pound cake.” I eat the rest out of politeness, though it tastes like stale flour.

A group of coyotes yips in the distance. “I got a little baby I want to bring out here and hold by the firelight,” Doc says. “I just don’t want all these other fuckers around while I’m doin’ it.” He says he wants to bring his daughter, too. “She’s a sweetheart of a girl.” He remembers that she once posted on Facebook that she would just like to lie in the back of a pickup and look at the stars. We sit there silently, staring up at the sky.

Two hours later, Ghost picks us up. On the way back, our convoy stops suddenly. There is a stack of stones by the side of the road that Bull, a thick-necked bounty hunter from Alabama, is certain wasn’t there before. We pile out of the trucks. Rogue tells us this is how the cartels mark their drop-off points. Doc thinks he sees a light, but it turns out it’s his own flashlight reflecting off a road sign.

Late one night in August 2014, heavily armed 3UP members came upon three men on a ridge near this spot. The militiamen shouted to them in Spanish, ordering them to sit and wait. The men hid behind rocks and announced they were American citizens. They made their way back to their campsite and the militiamen followed. The Border Patrol showed up and found that the men were scientists who had been counting bats in a nearby cave.

Back at the base, Captain Yota, a former Marine sniper with a long, sculpted beard, is amped up, and so is Rogue. They say the cartel rolled up on them while we were out. After they’d dropped us off, a teenage boy and girl, both Latino-looking with American accents, pulled up in a Honda and asked them for directions. “Are you boys the Minutemen?” Rogue recalls the boy asking.

“Fuck no,” Rogue told him.

“Isn’t this area run by such-and-such cartel?” Rogue recalls the boy saying.

“We’re like, ‘We’re hoping we run into some of those fucks,'” Yota recounts. “‘We’re gonna shoot ’em in the face.'”

“You really see them out here?” the boy said. “That’s crazy! You boys got rifles? Can I take a picture?”

Everyone agrees the boy was a cartel scout making a “soft contact.”

The situation reminds Yota of getting pulled over by a Mexican American cop earlier today because his license plate was obscured with mud.

“Who you with?” Yota says the officer asked him.

“The militia,” Yota asked.

“What are you doing down here?” the officer asked.

“Hunting Mexicans.”

In the morning, I pour some coffee into a tin cup and wander over to the fire pit. Rogue and Iceman are having a lively discussion. “My favorite is the one where the first stab goes under the clavicle,” Rogue is saying, “then in one of the lobes of the lungs so they can’t scream.”

“My favorite is where you come up and grab ’em by the throat and insert the knife right there,” Iceman says. He points to the hollow at the bottom of his throat. “Then rip from the left and to the right.”

“This one is two motions,” Rogue says. “A down stab and a side stab. You go down and puncture the lung, so they can’t build any compression to scream, and when you come across, you’re shooting behind the throat.” He demonstrates the quick two-step motion in the air—”Then you just hold ’em till they quit kicking.”

“Another good one is just frickin’ reach up and just stab ’em in the back of the frickin’ brain stem,” Iceman says.

“Eh, that’s harder than people think,” Rogue says skeptically. “You got a helmet on. It’s dark. You’re movin’.”

Everyone sitting around the fire but me is from Colorado. I’ve been noticing that the Arizona guys huddle around a separate fire pit by the kitchen tent. They hold their own meetings and their own ops. Captain Yota says that when he was taking a piss in the woods, he heard one of the Arizona guys whining about how the Colorado guys don’t leave the base with battle buddies like they are supposed to. “I’m holding my dick, and I’m like, ‘What, motherfucker?'” Yota says. “Chickenshit bastards.”

“Asshole,” Ghost says. “Pretty sure this will be the last op that we see the Arizona boys.” Ghost says some of the men from Arizona recently refused to follow his leadership.

“Fuck no,” Yota says. “They’re ostracized. They want to do that bullshit? Fuck ’em.”

Arizona and Colorado are by far the most represented states on the base. The Arizona guys, who run border ops year-round, feel that this is their turf. The 3UP leadership, however, is from Colorado. There might be a coup brewing. Why should Arizona report to Colorado? Should there even be a national leadership? Then there is the bigger question: how to unify the militia movement more broadly. 3UP has previously coordinated with Arizona Border Recon but does not currently do so. In these ever-tenuous militia alliances, leadership inevitably becomes a point of contention.

A ranking officer of the California State Militia told me that breakaway factions could become foes. “They are a possible threat. We don’t know what their intentions are, but they know all of our strengths and weaknesses.” He was in the process of reaching out to the state’s myriad breakaway groups because someday his men might find themselves traipsing through another militia’s territory and he wanted to make sure they were recognized as allies, not enemies.

Homegrown Soldiers

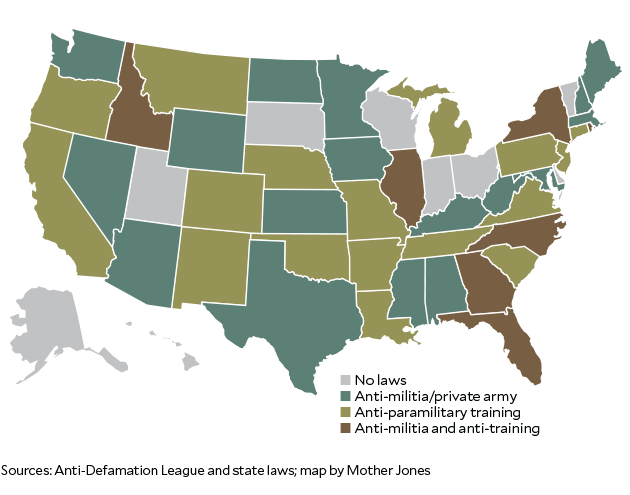

Forty-one states have laws that prohibit or limit paramilitary training and unofficial military forces.* Arizona bans the keeping of “private troops.” Colorado’s anti-terrorism law prohibits training people to use guns to promote “civil disorder.” California explicitly forbids two or more people from practicing with weapons as part of a group that teaches “guerrilla warfare or sabotage.” Yet, according to Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow with the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism, there isn’t a known case of these laws ever being enforced against private militias.

It’s not as if evidence of paramilitary training is hard to find. A man in West Virginia posts videos on Facebook of strafing exercises he does with his militia using an actual combat helicopter. I emailed a militia in Texas that told me it practices ambush tactics, shooting blanks at each other. Pitcavage says anti-paramilitary laws are difficult to enforce because typically prosecutors need to prove that the training is intended to cause civil unrest. And there is an added concern among law enforcement that going after a group simply for training “could backfire and make them feel persecuted or victimized,” further radicalizing them.

By calling themselves militias, paramilitary groups claim to be protected by the Constitution. “America has a rich history of the militia,” a California State Militia member told us at a training. “Men would get together in their local community and organize and say, ‘Hey, I’m here for you. You’re here for me. If something happens over at your farm, we ring the bell in town. Everybody comes. And we protect each other.'”

Militias and the Law

Forty-one states have laws that limit or prohibit private military groups or paramilitary training. However, there is no record of these laws being invoked against patriot militias. Read more on how law enforcement turns a blind eye to militia activity.

Yet this historical depiction is a “fantasy,” says Pitcavage. While today’s militia movement is made up of grassroots groups with the self-proclaimed mission of protecting the country against a tyrannical federal government, the militias enshrined in the Constitution were heavily regulated, top-down organizations.

Militias were originally a creation of the colonial leadership, and participation was mandatory. They were tasked with defending the colonies from hostile French and Spanish forces and their Native American allies. In the South, militias also patrolled for runaway slaves. After 1775, the militias were deployed to help defend the colonies against the British army, though George Washington lamented their “behavior and want of discipline.” After independence, participation in what the Second Amendment enshrined as the “well-regulated Militia” was mandated by federal and state law. Forced militia enrollment became so unpopular that by the middle of the 19th century, states found a way to get around it. All able-bodied men were still technically required to belong to a militia, but those who wished to participate could join the “organized” militia, which was trained by the state and eventually evolved into the National Guard. All other men were lumped into the “unorganized” militia, which had no responsibilities and essentially faded into obscurity.

Yet the stipulation that every able-bodied man between 17 and 45 is an automatic member of the militia is still on the books. Modern militias cite these arcane provisions as their legal justification. But Pitcavage points out that these laws make no allowance for privately organized militias. “It’s like saying the fact you are registered for the draft means you can organize an Army battalion,” he says. Patriot militias overlook that detail, just as they overlook the historic age limit on militia service. “When they wrote that, when you were 45 you were ancient,” said the executive officer of the California State Militia’s Delta Company, who looked to be in his late 40s. “I mean, come on.”

I am assigned to Bravo team for an afternoon op. There are three of us. “I’ll take the lead,” Iceman says. “I want you in the middle,” he says, pointing to Sandstone. “You’re gonna cover our six,” he says, indicating that I should watch the rear.

We pile into The Moose. Iceman tells me to rack my rifle’s chamber. I usually leave it open for added safety, but I don’t want to seem like a wimp, so I load it without hesitation—chk-chk.

Iceman is a lanky 28-year-old with a thick black beard and a short mohawk hidden under his boonie hat. A transparent, coiled wire in his ear is attached to a Chinese Baofeng radio. An AR-15 hangs in front of him and a long combat knife is strapped to his waist. He has eight 30-round magazines attached to his chest rig as well as some clips for the sidearm strapped to his leg. He wears head-to-toe MultiCam, hard-knuckled combat gloves, kneepads, and a patch specifying his blood type. Another patch says, “Colorado 3UP RRT,” denoting him as a member of the Rapid Response Team, the group’s special-forces unit.

Sandstone is similarly dressed, except instead of carrying a rifle, a long sword is strapped to his back, the handle wrapped in Army-green paracord. A sheathed machete is attached to his chest. Slender, with a shaved head, a pink face, and a wispy red goatee, he often grimaces dramatically, as if in pain. Unlike Iceman, who jokes on occasion, Sandstone is always serious, even when he spritzes himself with the MistyMate strapped to his back.

Reader support gives us the independence to dig deep where others in the media don’t. Help us do it by making a tax-deductible donation to MoJo today.

During the long, bumpy drive over the mountain, Sandstone barely speaks, but Iceman tells me about himself. Seven years ago, shortly after high school, he wound up homeless, living out of his car. He joined the Marine Corps and was sent to Afghanistan. There, he searched cars entering his base for bombs and drugs. He was glad to leave, but it didn’t take long before he felt that he was “scratching at the walls” of the hole he’d escaped by joining the military. Life still seemed stacked against him. He was working at a Subway and had a baby with heart problems. Sometimes he found himself hungry and penniless.

Iceman lay awake at night and wondered about the way of things. Why don’t veterans get the recognition they deserve? Why is the country so divided? He had a sinking suspicion that the government was behind it all. Racism had been nearly extinct—he didn’t care about race—but then Obama stoked the flames and now black people were marching in the streets. Was the government trying to start a race war to make it easier to enact martial law so that Obama could secure a third term, bring in UN troops, and launch the New World Order like George Soros and the big bankers want?

There were clear signs of government overreach—the National Security Agency, everyone knew, was spying on us. Then there were the other things Iceman had read about on the internet, like FEMA’s construction of internment camps for American citizens. He revered people like Edward Snowden who took action against the government. Iceman started to believe it might be necessary to take up arms someday, not as a soldier, but as a citizen. After joining 3UP, he felt like the hole inside him began to fill. “This is therapy, I guess,” he says as we careen down the dirt road. This is his third or fourth border operation. The first time, he was jumpy. “This is all too familiar,” he says. It reminds him of Afghanistan. “It’s hard to believe, right? We got a war zone in our own backyard.” None of the 3UPers have ever actually been shot at in Arizona, but that seems to be of no consequence.

Iceman and Sandstone discuss intimacies and betrayals back home. They are clearly good friends, but their friendship exists within a hierarchy and Iceman has higher rank. Sandstone sometimes calls him “sir” and salutes him, even in casual conversation.

As we drive, our convoy stops on occasion to drop two-man squads along the road, each executing a different mission. We drive far into the desert, until we’re within sight of the border fence. Ghost gets out of the truck, points to a saddle on a distant mountain, and tells us to walk toward it until we hit Duquesne Road several miles away. My squad, Bravo, and the other squad, Alpha, are to spread apart, sweeping the area. “This is not a race,” Ghost says. “You’re whitetail huntin’. You’re stalkin’. You got from now until dark to make it back to Duquesne Road, okay? You got plenty of time. Heads up: These guys will probably see you before you see them. If that’s the case, the fuckers will get down on the grass. So take your time.”

He drives away and we all check our weapons to make sure they are locked and loaded. If we see someone who looks like an immigrant, my understanding is that we are to radio the base and it will alert Border Patrol. But no commanding officer has ever made the protocol clear to me. How do we detain the person? At gunpoint? What happens if we see someone jump from behind a bush and run? (Fifty Cal later told me he had briefed members on what to do, instructing them, “Our job is very close to a mall cop. Observe and report. You cannot chase anybody down. You cannot handcuff anybody. We’re not an offensive group.”)

“I suggest blousing your boots,” Iceman says to me. “Keeps critters from getting up your leg. You don’t want a bug biting your cock.”

“No,” I say. “I don’t.” I bend down and cinch the bottoms of my pant legs.

It’s windy and the sun is blazing in the cloudless sky. At the top of a small hill, Iceman takes a knee and Sandstone and I do the same. For several minutes, we look out over the valley, mottled with creosote bushes, sotol, and grass. I sense that for them, there is a romance to this—the open land, the distant mountains, the belief that they are defending the frontier in service of the nation. I, too, relish this moment. Like them, I have a rationale for my attraction to danger and violence. I, too, am here.

We walk down the hill and enter a narrow, sandy wash. Iceman bends over a patch of sand and points to the ground. “That’s a footprint, isn’t it?” Sandstone says.

“Yep,” Iceman replies. “That’s a moccasin.”

“Carpet shoe?” Sandstone says.

“Yep,” Iceman says. “Straight-up carpet shoe.” I look closely at where he is pointing and I see nothing but dull waves of sand identical to those throughout the wash.

“Should we follow them?” Sandstone says.

“Yep.”

The Resurgence of Militias

The number of militia and anti-government “patriot” groups spiked in the ’90s during the Clinton administration and then quickly declined during the Bush years, only to surge again after the election of President Barack Obama. Read more on the history of American militias.

This dynamic continues for a good while. Sandstone points out new moccasin prints that I cannot see, Iceman says “yep” without hesitation, and we head off in a new direction. At one point, Sandstone finds a piece of cellophane that he determines to be the wrapper of a phone battery. He crumples it in his hand and confidently leads us on yet another course.

Sandstone is observant. He takes photographs of airplane contrails and altocumulus cloud patterns and posts them on Facebook as evidence that the government is spraying us with chemicals and conducting surveillance. He reads up on things: the Bilderberg Group, the Rothschilds, and what really happened on 9/11. He does not consider himself left or right, though he does support Trump as a matter of practicality. He swings a sledgehammer and breaks concrete all day and has little to show for it. Why should he have to compete with anyone who will work for less?

I hear a voice over the radio. It’s Bull. He and Geezer are near the top of the mountain, and they have intel to relay: There is an all-terrain vehicle at the border fence, and another ATV and a white minivan are driving toward it. Captain Yota chimes in over the radio, reminding Bull that people do use this area for recreation and it is the weekend. The ATV at the fence, Bull replies, is playing Mexican music.

We walk for 20 minutes until we come to the edge of a 10-foot ravine. At the bottom, there’s a backpack, a blanket, a couple of jugs of water, and a pair of blue jeans, supplies likely left for, or by, migrants. There is another backpack nearby. Iceman and Sandstone become tense. As if on cue, a coyote yips, startling all of us. For a few seconds, I raise my weapon and point it off in the distance, scanning the horizon to defend against an ambush. “Cali, I want you to cover our six,” Iceman says.

“Got it,” I say.

They climb down into the ravine. Iceman nudges the backpack with his foot. He orders Sandstone not to open it and speaks into his lapel mic: “Relay is that we have found several backpacks, along with a duffel bag, that have significant weight to them.” Captain Yota tells him to see what is inside. “Solid copy.”

Sandstone opens a backpack and pulls out anchovy and tuna packets, Snickers, suckers. He and Iceman open the other one, pulling out shoes, fresh clothes, and more food and candy. There are full water jugs at 20-foot intervals up the ravine. In a crevice, Sandstone spots a Mexican blanket, tightly wound with a rope. He unsheathes his sword, cuts the rope, and unfurls the blanket. Nothing inside.

They start to climb out of the ravine, but Iceman stops. “You know what?” he says, pulling out his long combat knife and marching back to where he came from. He swings and jabs a jug, spilling the water onto the sand. He marches over to the next one and stabs it passionately. I almost ask him to stop—this water could be someone’s lifeline—but it does not seem wise. He stabs each item meticulously—the candy bars, the tuna packets. Sandstone follows behind, stomping the food into the dirt.

When they are done, Sandstone sheathes his sword and we continue our journey north. A hundred yards from the ravine, Iceman stops. “Y’alls didn’t see me stab those water jugs,” he says.

“What water jugs?” Sandstone quips.

We continue on quietly for a while.

“I tell you what, it felt good stabbing them fuckin’ water bottles,” Iceman says, “knowing they ain’t gettin’ no water.”

“It felt good stomping all that shit into the dirt,” Sandstone says. “They’ll be expecting a change of clothes, a change of fucking shoes, three gallons of water, and some tuna fish.”

“And some fuckin’ candy,” Iceman says. “And what are they gonna get? Nothin’!”

We walk down another wash, where the shadows have become long and the light golden. We stop, drop our bags and rifles, and sit. Sandstone eats some crackers and gives a Slim Jim to Iceman, who is scraping burrs off his boot with a knife. Nearby, a gnarled, sunbaked shirt is lying in the sand. Sandstone gets up, walks over, and pisses on it.

“Anything Can Happen”

By the time we are picked up, it’s dark. I pull my tube mask over my face to protect against the freezing air in the back of The Moose. There is a flurry of alarmed radio chatter about a heart attack on the base. Ghost races back over the mountain. A helicopter blocks us, sitting in the road with Border Patrol vehicles scattered around. “Go ahead and pull security,” Captain Pain tells me and the other men in the bed of the truck. We stand at the edge of the road, our weapons at the ready, and stare out into the black desert. With the patient inside, the helicopter lifts off, fades into a dot of light, and vanishes over the mountains.

The base is tense. During the medical evacuation, the Colorado leadership was in the field. The Arizona guys took charge and refused to stand down once Colorado tried to assert control from afar. Now the Arizona guys gather around their fire pit while Blackfin lectures some of the Colorado crew. “Pride will get you killed,” he says, a slight against Arizona’s refusal to relinquish control. “Pride will get everyone else killed.”

Bad decisions were made, Blackfin says. Instead of standing around, men should have staked out the perimeter immediately. “Your enemy will kill you at your weakest point. Suicide bombers? They’re gonna get you at your weakest time. It’s easy and it’s effective. As soon as something chaotic happens, you still need to pull security.” We shouldn’t wait for someone to tell us to do things like this—it should be automatic. “That’s what we do here. We’re alpha leaders. Even if you don’t want to be. You have to be—or you will die.”

I listen to this talking-to with Iceman and Sandstone, but since we were out on an op, we are comfortably not implicated in any of this. Then Captain Yota starts to speak. He is furious. He asks who was using a cellphone to navigate out in the field. I raise my hand. After following Iceman and Sandstone for more than two hours, I had checked my phone’s map to see how much farther we had to go.

“People get so used to fucking technology,” Yota says. “You know what I had in the Marine Corps? I had a fucking protractor, a fucking 1-by-50,000 grid fuckin’ map, and a compass. Holy shit! I mean, we’re out here to do a mission and catch bad guys, right? To find drugs, catch illegals? How the fuck are we gonna do that if we can’t do our simple-ass job?”

“Shit, man, I got left for dead in fucking Iraq,” Yota continues. He was a sniper for eight years and claims his lieutenant abandoned him and his spotter near Ramadi. “My FOB was seven miles away. I had to go through fuckin’, a goddamn town that’s full of bad guys to get home.” He says he got back by “offin’ motherfuckers.” “Guess what, I’m here, right?” He throws up his hands in frustration.

He is also angry about how my team handled the backpacks. Iceman should have taken control of the situation and searched the bags without calling it in. “If it’s fuckin’ drugs, back the fuck away from it. Take pictures and secure the shit. Don’t touch it! But if it’s fucking food and water? Destroy the shit. Okay? ‘Cuz there’s a lot of humanitarian groups that drop off food, water, and everything to these fucking bastards who come into our country illegally.” Fifty Cal later told me, “We would never deny food and water to an immigrant.” He said this cache was clearly meant for a drug cartel, given the “high-dollar items” in the backpacks.

I bolt awake to my alarm at 3:15 a.m. I’ve been appointed to stand the late-night watch. I walk to the fire, where Bull is sitting, his baseball hat pulled low over his eyes. There always seems to be something simmering inside him. His shoulders are tight and when he speaks, it’s usually in a low, angry drawl. He is with the Borderkeepers of Alabama. I ask him what they do, given that there is no border there. “Companies have had to close their doors because they can’t compete with some fucking illegal taking cash under the table. Nobody can compete with that. They fuck up everything.”

One time, Bull was at a gas station and a Mexican man was trying to buy alcohol, he tells me. The cashier asked for his driver’s license, but all he had was a Mexican ID. Bull came up behind him. “You don’t have a driver’s license?” he asked the man. He says the man pushed past and got into his car. “So I’m like, this is easy as fuck,” Bull recalls. He called the cops and reported the man for driving without a license. But when the cops showed up, Bull says, they focused their attention on him rather than the Mexican. “What’s your interest in asking him if he’s driving without a license?” a cop asked him. Bull tried to school the police on his power to make a citizen’s arrest and then he left, outraged.

When he came to Arizona for his last border operation, he scooped up some dirt near the border fence, put it in a bag with some flowers, and brought it back to Alabama. He tracked down the cop he’d argued with and gave him the bag. “He was fuckin’ pissed,” Bull says. “That’s when I figured his old lady was an illegal or something.”

The news crew, from a CBS affiliate in Alabama, has been following the Borderkeepers. They ride along in the back of the militiamen’s trucks, shoot interviews, and spend a lot of time in their air-conditioned car, which is seen as a sign of softness. Guys talk with them readily, but I am careful to avoid them, so as not to appear in their footage.

In her segment on her time here, reporter Brittany Bivins tells viewers that the Borderkeepers are “people who really live in our neighborhoods” and who “spend their vacation time, they spend their money, to go down to the border, and they’re very passionate about what they’re doing.” Bivins links the border op to the heroin epidemic back in Birmingham. She says cartel spotters watch the base and the drug smugglers are “fighting back,” though she doesn’t go into detail. “Anything can happen on the border,” she says. One of her main sources is Bull. Bivins tells viewers they can find the Borderkeepers on Facebook if they want to get involved.

Bull tells me that when he was sitting up on top of that hill watching the ATV near the border fence, he saw “Mexican males” coming and going from a vehicle playing Mexican music. It was obvious what was going on. “I had my sight on ’em,” he says. “I wish I coulda picked those motherfuckers off. If only we didn’t have our hands so fucking tied.”

Spirits are high as we stand around the fire at night. Ghost regales us with stories from past ops and tells us about the tradition of no-pants Mondays on the base. Too Tall talks about a trip he took to the hospital with Cornbread, who’d gotten dehydrated. “You want to see cartel? Go to the hospital,” Too Tall says. “Cadillacs, Malibus. Every motherfucker up there was stopping by my truck.” Cornbread says he wanted to throat-punch the Mexican man in the hospital bed next to him. “That motherfucker didn’t have to pay shit. And they charging me out the damn ass for it. And somebody’s getting the same treatment for nothing. It’s bullshit.”

Denver comes up behind Ghost and hands a cigar over his shoulder. Ghost is very pleased. “Did you get you some Cubans now that the nigger opened up the border?” he asks Denver. Ghost lights his, flaring out his lips and biting down on it with his front teeth. Someone makes a joke about how cigars are like horse cocks.

Staring at me across the fire, Sarge, a large twentysomething man in a keffiyeh, declares he’s saving his cock for me, and everyone looks in my direction. “‘Cuz California’s got that tight little socialist butthole,” Sarge says. “I’m about to bring some democracy up in that motherfucker.” Everyone laughs. “I’m gonna bring some free trade up in that ass.” I laugh uncomfortably until the attention fades. Most of the harassment in the camp is directed at the lone woman from Arizona, a blond, tattooed prison nurse who works in a solitary confinement unit. Guys thrust their pelvises at her when she’s not looking. “I got the cure for what ails you,” Sarge tells her. He also calls me “baby girl” and tells me I have a pretty mouth. I consider sleeping with my rifle in my tent.

Sarge falls into a side conversation that moves from sex to the Department of Veterans Affairs. “Imagine me talking to a psych evaluator at the VA? Noooooo. They tried to give me a lot of pills. I said nope.”

“They told me I was already nuts,” Rosco says. “I was like, ‘Yeah.'”

“That’s what they do at the VA.” Sarge says. “They just throw a shitload of pills at you.”

“You’re basically a lab rat,” Too Tall says. “They just pump as much shit in you as possible.”

I get up from my stump and stand with Jaeger and Destroyer. Jaeger is insisting that the Mexican military sometimes drives its Humvees over the border and shoots at the Border Patrol.

“Time to put some Apaches on the border,” Destroyer says.

“Last year in June, a Mexican Apache flew from their base down in Mexico all the way into Phoenix,” Jaeger says matter-of-factly.

“No shit?”

“Yeah, over military bases and whatnot,” Jaeger says. “The sad part is the Air Force base that’s down there. They went to scramble jets and they were ordered to stand down.”

“Wouldn’t you know?” Destroyer says. “They fucking invaded! Holy shit!”

“Yeah, it’s almost like they are testing our borders for military purposes.”

“Yeah, no kidding.”

Campfire smoke suddenly wafts in our direction. “Stop attracting the smoke, Jaeger!” Destroyer says. “Dammit!”

“Just because I like to burn people,” Jaeger says mock-defensively. Destroyer laughs. It’s a “homemade Auschwitz,” Jaeger says. “It just takes a lot longer. Hahaha!”

Jaeger tries to speak to Destroyer in German, but it’s often too rudimentary for Destroyer to understand. Destroyer is fluent; he was born and raised in Switzerland and served in the Swiss military. It strikes me as strange that someone raised in Europe would get involved in the patriot movement. He says he was home-schooled by his American mother. “I was taught the right stuff,” he says.

Destroyer recalls a time he came to the United States through Canada with his family. They had to wait two hours at the border because his dad did not have a US passport. “Dude, they took my dad out, fingerprinted him, basically treated him like a common criminal. Spent two hours on the Canadian border. It’s fucking bullshit. It’s like, does he look like a criminal? We’re a family of seven, you know?”

Someone asks where a guy called Wolfman is. Rogue says he left today. “He had to go home and take care of some bullshit,” Yota says. “Bullshit with an ex and a kid, I’ll tell you that. Some drama shit he’s gotta go to court on Monday for.”

“Shitty ex-wife.”

“Most of ’em usually are,” Jaeger says.

“And they wonder why bitches get killed,” Yota says.

“Hahaha!”

“Seriously. They push and push and push till you can’t take it no more. Then the dude ends up fuckin’ offing ’em. Then the dude looks like a fuckin’ evil-ass person and it’s like, dude, you were pushed.”

“You want to know what the No. 1 reason listed for men committing suicide is?” Jaeger says.

“Women,” Yota says.

“Exes taking away their kids,” Jaeger says.

“I haven’t seen my boy since he was four,” Yota says. “I know where they live and everything. You know how tempting it is to just go see my kid?”

“Snatch and grab,” Destroyer says.

“But I know if I go I’ll end up in fucking jail.”

“Women are fucked,” Jaeger says.

“They always win in court,” Destroyer says.

“I’ve won every court case,” Yota says. “Every court case. And what she does is she moves to another state ‘cuz the case follows the kid and then I’ve got to file in that state.”

“And that just costs you a lot,” Destroyer says.

“I’ve gone through almost $22,000. Then I just gave up—well, I ran out of money. Used all my deployment money fighting on this shit. Didn’t get nowhere. I figure if he’s anything like me, I’ll get a knock on my door when he’s 13. That’s when I turned into a little bastard.”

“Did you ever outgrow it?” another guy says.

“No, I’m still an asshole. I just went to the Marine Corps and that made me an even bigger asshole.”

“They paid you for it, right?”

“But I’m a true motherfucker.”

“Are you really an asshole if you speak the truth?” Jaeger says.

“Not really,” Yota says.

“There you go,” Jaeger says.

Survival and Evasion

One day, I ride into town to resupply with Captain Pain, Showtime, Destroyer, and Jaeger. We stop at Pizza Hut. Everyone takes advantage of the cell reception to check Facebook. Captain Pain has an online business selling threeper holsters, shirts, and decals. He shows us a picture of a big-breasted woman in a bikini on Instagram.

“So who’s in charge of waterboarding this time?” Captain Pain asks.

“Mostly me,” Showtime says, barely looking up from his phone.

“You’re waterboarding people?” I ask.

“Yeah,” Showtime says with a jolly half-smile.

“You probably can’t even call it waterboarding,” Captain Pain says. His tone is very reasonable. “You know those little water bottles we have at camp? I’ll pour it around their nose and around their mouths, but not a lot of it gets in there.”

“That’s ‘cuz they’re upside-down,” Showtime says. “Then they try to hold their breath, so we tase ’em in the armpit. Hahaha!” He makes like he’s tasing himself in the side.

Showtime explains that the waterboarding and tasing are part of their SERE school—Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape—for recruits to the Rapid Response Team, 3UP’s special forces. “I think it’s a really vital course,” Captain Pain says. “If they snatch you up out here, it’s really gonna be fucked up.” The course starts in the middle of the night, when the recruits arrive at Captain Yota’s house in the mountains. They sleep in their cars, and early in the morning they’re woken up and made to do physical training until they “fall out.” Then they get “captured.” “We’ll put a bag on their head, cuff ’em, strip ’em down,” Showtime says. “They just got a big-ass T-shirt on. So it gets pretty cold in January. Hahaha!”

The recruits are told to imagine they are out in Arizona and have been captured by a drug cartel. They’re put in a stall in a horse barn and subjected to sleep deprivation. “We keep ’em up. Keep ’em hungry,” Showtime says. The mock detainees are cuffed to a table sloped at an angle and asked questions like how many people are in their group and what radio frequency they use. Their task is to resist giving any information. “We got a stress box,” Showtime says. “We put ’em in there. Stick a cattle prod through the holes. One guy, he tried to turn around and we got him right between his legs in the ball sack.”

“Yeah, too much fun,” Destroyer says.

“How long were they sitting there?” I ask, trying not to sound alarmed.

“Couple hours,” Showtime says.

“I don’t think we’ve kept anybody in the stress box that long,” Captain Pain interjects.

“It gets cold, but they get warm right away if you put three of ’em in there,” Showtime says.

Sometimes when Showtime interrogates people, he cuffs them to a metal chair. “I’ll take battery charger cables and hook it up to the chair,” he says. “The cord is broke, but they don’t know that.” Showtime will occasionally stand a habanero-covered dildo on the table in front of them and tell them to suck it. If they resist, he shoves it into their faces.

One time, he says, they tied a man upside-down on the tilt-table with his arms stretched over his head. Fifty Cal filled a syringe with hot sauce, dripped some hot sauce on the man’s lips, and said, “This is going in your dick hole.” Then Fifty Cal took a syringe full of water and dripped some on the man’s penis. The man, thinking it was hot sauce, shouted, “I quit! I quit! I quit!”

Captain Pain stresses that the recruits can drop out anytime they want during the roughly 40-hour training, and many do. They’re also recorded on camera consenting ahead of time.

“You ever get people flipping out?” I ask.

One guy “was ready to pound my ass,” Captain Pain said. “He was ready to just fuckin’ destroy me.”

“What put him over the line?”

A female member of 3UP was in the room, he says. “I fucking had her by the neck with a Taser. I told him if he didn’t tell me something I was gonna light her up. He just looked at me, so I lit her up. That’s not working, so I get a cattle prod. Lit her up. Hit her in the calf.”

They’ve gotten some complaints. “People were like, ‘What the hell, you’re running a torture class?'” Showtime says in a high-pitched, mock-weakling voice. He laughs.

When I asked Fifty Cal to comment on the training, he wrote back, “Stories of SERE are greatly exaggerated. Yes, we have a version of SERE; it’s more of a gauge of mental awareness than anything to do with torture.”

“Everybody that went through it said it was awesome,” Ghost told me. “Nobody got hurt. Nobody died.”

Our reporters can go after stories that are hard to get but need to be told, thanks to support by our readers. Join us by making a tax-deductible donation to help fund MoJo‘s investigations.

Fifty Cal comes out of his trailer and tells us to rally up. “Let me see hands of everybody that’s got night vision out here. Who’s got the good shit?” A bunch of people raise their hands. Fifty Cal appoints some of them as squad leaders and tells them to each pick two men for their team. He tells us we are going back to the area where Sandstone, Iceman, and I found the water and backpacks. We’ll sweep through in five teams. Someone points out there is no way to cross that area without going through private property. “It’s gonna be dark,” Ghost says. “As long as you guys aren’t shooting, yelling, and screaming, I don’t think anyone’s going to know we’re even going across it.”

At 7:30 p.m., I get into the back of a truck with Yota, Bull, Jaeger, and Destroyer. “Fuck yeah,” Yota says. “Let’s go play, boys.” Yota gives instructions to his squad. If they run into anyone, he will make contact, Destroyer will take pictures, and Bull will be the “trigger man.” “Don’t let them fuckers smoke my ass,” Yota says.

“Does anyone here know Spanish?” Jaeger asks.

“I know a little bit of Spanish. ‘Stop,’ ‘sit down.’ Alto! Siéntate!” Yota says.

“I know ‘chupa mi verga,'” Spanish for “suck my dick,” Jaeger says.

“If they don’t speak English, they’re fucked,” Destroyer says.

“You’d think if we were out here hunting Mexicans, somebody would speak goddamned Spanish,” Yota says.

“Yeah, but do you know how to freakin’ talk to a damn deer when you go deer huntin’?” Bull says.

“Yeah, you just shoot the motherfuckers.”

My blood feels like an electrical current. Is this, ultimately, why they do this? Maybe what drives them is not just the fear of illegal immigration or the New World Order, but this feeling I am having right now—nerves exploding, blood coursing: alive.

Five squads of three get dropped off at 300-yard intervals along the fence. I am with Showtime and Jaeger. Showtime, whose face, as always, is painted green, tells me to take point and navigate directly north. Flashlights are out of the question, so I let my eyes adjust to the light of the crescent moon, pull out my compass, and lead the way. Every few hundred yards, Showtime stops, takes out his night vision goggles, and scans the terrain.

We make our way slowly for two hours. From time to time, I bump into spiky bushes, scratching my face. Then I hear voices ahead of us. It’s Bravo team, talking with three Border Patrol officers. Minutes ago, an officer had approached Yota, Destroyer, and Bull, shouting to them in Spanish. Yota yelled back, “Alto! Siéntate!” and aimed his rifle at the officer. After a tense moment, they all put down their weapons.

The six of us follow the agents quietly back to the road. Fifty Cal and Ghost are standing at the roadside. I turn on my body camera.

An agent named Dennis, his baseball cap cocked backward, introduces himself to Fifty Cal. He says he is an intelligence officer for the Border Patrol, and he tells Fifty Cal and Ghost they’d spotted us using infrared technology.

“Y’all ever seen an AR pistol?” Yota asks the officers. They walk over to a 3UP truck and Yota hands his weapon to the second Border Patrol officer, whose name sounds like Ford. Ford turns it over, looks it up and down, and aims it. Then Fifty Cal brings over his .300-caliber AR-15 and Ford handles it with awe.

“I love my job,” Dennis says. “I have days where I’m like, ‘Fuck this. This is the worst mistake I’ve ever made.’ But most of the time, if I sit back and I think about it, I come in and play hide-and-seek, steal weed off of people, steal vehicles from people—legally—and watch Netflix.”

“I love having y’all out here, man,” Dennis continues. “It impresses me that you guys come out and do my job for me for no pay at all.” He pulls business cards out of his wallet and hands one to Fifty Cal and one to Ghost. “Give me a good heads-up next time you guys are gonna come down. If you plan on coming to the Nogales area, since you’re out in Colorado maybe I can take a trip out and give you guys an unauthorized brief. Or at least give you something in writing so you guys can brief and whatnot.” Ghost and Fifty Cal shake his hand. “Then when y’all get down here I can link up with you again and whatnot.” He says he does the same with another militia that does ops down here.

“We’ll take all the help you guys will give us,” Ghost says.

“You didn’t hear this shit from me,” Dennis says.

Fifty Cal brags to Dennis about their survival training. “We have a great fucking prison. We have perfected the art of waterboarding. Hahaha!”

“We call it ‘freedom masking,'” Yota says.

“Yes!” Dennis says. “Yes!”

Fifty Cal tells the officers that 3UP once had a run-in with the Mexican military. The soldiers came up to the fence, pointing at them and asking, “US military?”

“They wanted to know how many,” Ghost says. “They wanted to know where our FOB was. They wanted to know a lot of shit.”

“I heard you say you were a sniper?” Ford asks Yota. “Mind if I ask you—” He hesitates, shuffling sheepishly. “I don’t have the right to ask you, so I won’t.”

“You can,” Yota says.

“What was the longest shot?”

“Nine hundred forty-six meters.”

“Movin’?”

“He was movin’. Left to right.”

“Nice,” Ford says. “You guys actually went and fought. I didn’t go. That’s on me.”

“Hey, you’re doing your service now, right?”

Ford shakes his head in shame.

“Hey, it’s the administration that’s fucking it all up,” Yota says. “I took an oath. I honor that oath. I got out in 2011. I went in in 2002. I’m out here honoring my oath again, serving while I still have an able body. That’s what we do.”

Ghost asks where there is a good place for us to set up and look for people. Dennis looks at Ford. “Witch’s Tit? Witch’s Tit. Perfect.” He tells Ghost how to get there. “If you sit there, you can watch all the way down, dude.” Ford says another group might be trying to do something out there. “Just a heads-up about that.”

Dennis offers to take us on a tour of the border road. That way, he can point us to Witch’s Tit and other spots for us to set up. We follow the Border Patrol truck on dirt roads for what feels like an hour, shining spotlights into the desert and along the fence. We occasionally stop and Dennis, Ghost, and Fifty Cal get out of their vehicles and talk apart from the rest of us.

When we get back to the base, I thaw my freezing hands by the fire. “Well, that was fun, wasn’t it?” Yota says.

“Yut,” Ghost says, staring into the flames. “Learned a lot of fucking shit.”

“Did he give you more intel in the end?” I ask.

“That dude’s given me more intel than any other fucker out here. Not to mention, he’s an intel officer for Border Patrol. He just told me the exact trail that they take. That’s why they took us on that drive. Then there’s Witch’s Tit. He said you just get on top of that. You can see everything up to Duquesne Road. He said that’s exactly where they come off the mountain pass, across Duquesne. They run right by ya.”

“I mean, from listening to him, he wants us to do his work,” Captain Pain says. “Which is fine.”

“Well, there’s a lot more of us than them,” Jaeger says.

“Well, that’s the thing,” Captain Pain says. “I mean, one guy out there by himself? If they help us help them, it’s gonna be more productive all the way around. In the end, they fuckin’ win no matter what.”

Shots Fired

Fifty Cal tells us to circle up. “We got two ops that we want to plan, based off the intel that we got from the Border Patrol last night about a drug run that may be coming in,” he says. “They showed us the area of the fence they come through and the rough times that they think they’re gonna be coming in. We’d need to leave camp at about 0300 tomorrow.”

A man next to me whispers to another, “They’re hard to chase ‘cuz they’re high as fuck. Their pace is twice our walking pace. That’s why the only way to really get them is to have a known trail. Put people in position along that trail. That’s the only way you can ambush ’em. Good luck fuckin’ chasing those sonsabitches.”

The day passes slowly as we wait. Jaeger, Destroyer, and Spartan sit and play cards under a tree. Jaeger is listening to a song called “Shadow of the Swastika” by a Viking metal band called Týr. “If you listen to the lyrics, they make a very good point,” Jaeger says. “They are saying, ‘We didn’t commit these crimes. Why should we be blamed for it?'”

This makes Destroyer think of Black Lives Matter. “They come along and say, ‘Pay us restitution,'” he says in a mock-stupid voice. “No one alive was enslaved!”

“The goddamn Irish dealt with more bullshit than the niggers,” Spartan says.

“Yeah!” Destroyer says. “There were literally Irish slaves. That’s never mentioned in history.”

“They’re not fucking pussies, that’s why,” Spartan says.

A Border Patrol agent stops in, hurried, and tells us some of their sensors were tripped just to the south of us. Doc and one of the Borderkeepers of Alabama gear up and take a position on a nearby hill. Fifty Cal tells us to stay alert.

The other day, a Border Patrol agent showed up with two boxes of doughnuts. I asked him whether they ever get any pressure from their superiors in Washington, DC, about us being around. “Not that I ever heard of,” he said. “When you guys come through, they warn us like, ‘Heads up, those guys are out there.’ Good!”

I later asked the agency to comment on these interactions between its officers and militiamen. A spokesman only replied that the agency “appreciates the efforts of concerned citizens as they act as our eyes and ears” but “does not endorse or support any private group or organization taking matters into their own hands.” Fifty Cal told me he’s still in touch with his Border Patrol contacts “pretty much weekly.” The agents “give us very useful information to help make our ops better,” including recommendations for times and areas to patrol.

Captain Pain says that with the new connection to Border Patrol intel, Colorado won’t need to rely on the Arizona guys for their local knowledge. Colorado can set up its own base next time. There is still the problem of equipment, though: The Arizona guys supply the kitchen and lights. Ghost says he has propane lights and gas burners back home. Pain says that when he gets back he’s going to try to get some gun shops to sponsor the border operations. They might try crowdfunding, too.

“I’ll let you in on a little something nobody knows but me,” Ghost says to the few of us sitting around. “We have 640 acres in Texas we can use. It won’t be ours, but it will be leased to us.” He says the land is directly on the border, so immigrants would have to pass right through it. The owner is a 3UP sympathizer. “That dude’s gonna give us free rein. We can build barracks. We can build fucking shooting lanes. We can do whatever we want to the property.”

“Catch fucking beaners,” Captain Pain says.

“Throw up a sign that says, ‘No Trespassing,'” Destroyer says. “Then we can shoot ’em.”

I don’t bother sleeping in my tent. I’m too exhausted to deal with the cold and the next op is only four hours away, so I get in the cab of my truck, lay the passenger seat back, and turn on the heat. I wake at 3 a.m., stumble past the guys around the fire, and pour a cup of coffee.

Ghost assigns Iceman and me to go up Witch’s Tit, the spot Dennis recommended. Iceman looks like an apparition from hell. He is wearing a nylon skull mask and a battle helmet with built-in night vision goggles that pull down over his eyes, which he’s blackened like a raccoon’s. By 5 a.m., we are hopping between boulders in a dry riverbed that snakes up a narrow valley. Iceman goes ploddingly, planning and executing each step. “Fuckin’ A, it’s pitch-black out here,” he whispers. He has an eye condition that makes him nearly blind at night, even with the goggles. He is breathing heavily, either from exhaustion or panic. When he takes his monster mask off, he looks remarkably vulnerable and afraid.

I take the lead. An hour into our patrol, I suggest that we climb the side of the mountain to get up onto the ridge, where we are meant to stand watch. It is steep and Iceman scrambles up using his rifle as a walking stick. Birds trill and a white-blue light is filling the sky. Eventually, we reach the top and sit, looking over the southwest side of the mountain. “Mobile One, Delta,” I say into the radio. “Delta is in position.”

“Solid copy.”