A crowd gathers at the lynching of Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas, in 1916.Library of Congress

On a Sunday afternoon in May, more than 100 people gathered on a grassy knoll sandwiched between a swamp and a construction company lot on the eastern outskirts of Memphis, Tennessee. Two high school juniors, Khamilla Johnson and Khari Bowman, stood before them and described how, exactly 99 years ago, a crowd at least 50 times as large had come to this very spot to watch the lynching of a black man named Ell Persons.

Persons, the teens recounted, had been arrested for the rape and murder of a white girl based on pseudoscientific evidence, such as a claim that his image was imprinted on her eyes. Before he could be tried, a white mob abducted him and brazenly announced the place of his torture and death. They chained him to a log, doused him in gasoline, and set him alight.

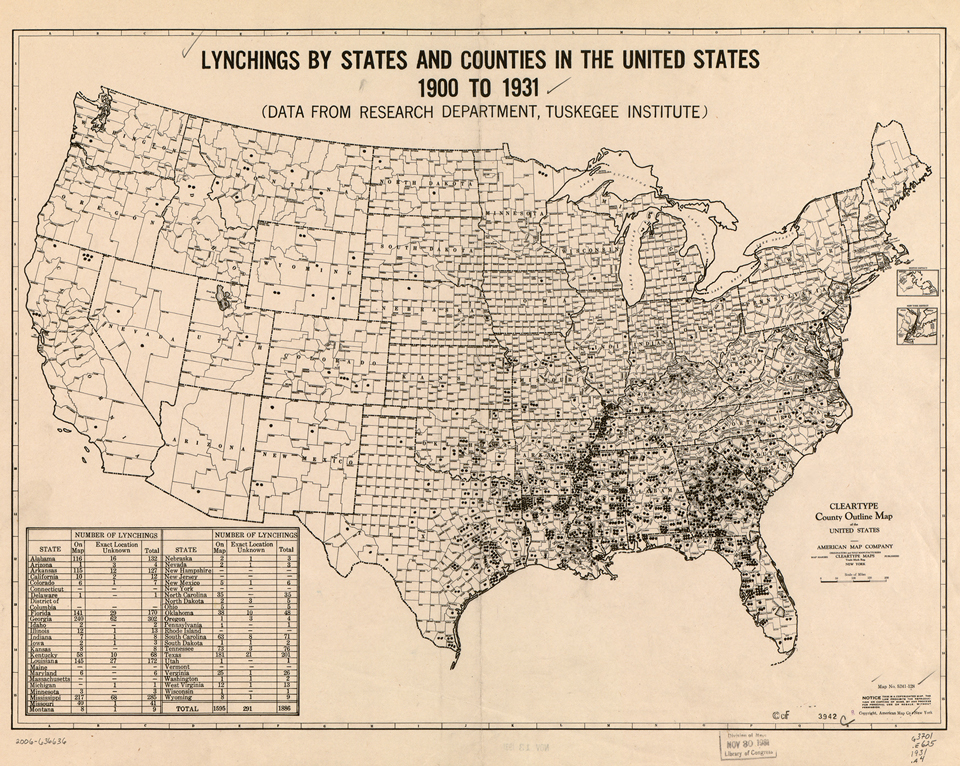

Afterward, spectators took pieces of his charred corpse as souvenirs. A photo of his decapitated head was printed on postcards. Accounts of the day described a carnival-like scene: Parents brought their children, vendors sold snacks, and cars lined up for more than a mile. “No one feared punishment, and no one was ever arrested for the crime,” Bowman said.

The memorial event was the launch of a campaign to stamp Persons’ name in Memphis’ civic memory. It was also part of a nascent movement to rediscover and memorialize lynching sites across the South. The effort is led by Bryan Stevenson, the executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, which has documented more than 4,000 lynchings of African Americans across 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950. (The New Yorker profiled Stevenson in this week’s issue.) So far, the EJI has placed plaques at five sites. A plaque for Persons will be erected next spring. And in November 2017, EJI plans to open a museum and national lynching memorial in Montgomery, Alabama.

After Johnson and Bowman learned about Persons during a history class project, they and their classmates rallied around Stevenson’s call to unearth past racial violence and recognize its modern echoes. “History repeats itself,” said Justyce Knowles, a classmate of Johnson and Bowman. “We were all so upset about Sandra Bland, about Trayvon Martin, about Tamir Rice. I feel like, let’s keep it trending. Let’s make it a hot topic.”