Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP Photo; Matt Rourke/AP Photo

When Tim Kaine moved to Richmond in 1984 to start his legal career, his first assignment was a pro bono case representing a black woman named Lorraine who’d been turned away from an apartment. The landlord had told her he’d already rented it out when she showed up to take a look at the place. But when she asked a coworker to call back later the same day, the landlord said it was available. It was a clear-cut discriminatory housing case.

Reflecting on the case last fall, Kaine—now a 58-year-old Democratic US senator from Virginia—said it prompted a “‘there but for the grace of God go I’ moment.” For Kaine, the act of moving to a new city to start his adult life, fresh out of Harvard Law School, had been “such a positive,” he said, but “for her [it] was a negative, getting turned away just because of the color of her skin.” He won that case and quickly became one of the few attorneys in Virginia focusing on fair housing, which would later constitute, by Kaine’s estimation, 75 percent of his legal practice. A few months after he became Richmond’s mayor in 1998, he won a $100.5 million jury verdict against Nationwide Insurance for the company’s discriminatory lending practices. It was the largest such award in history.

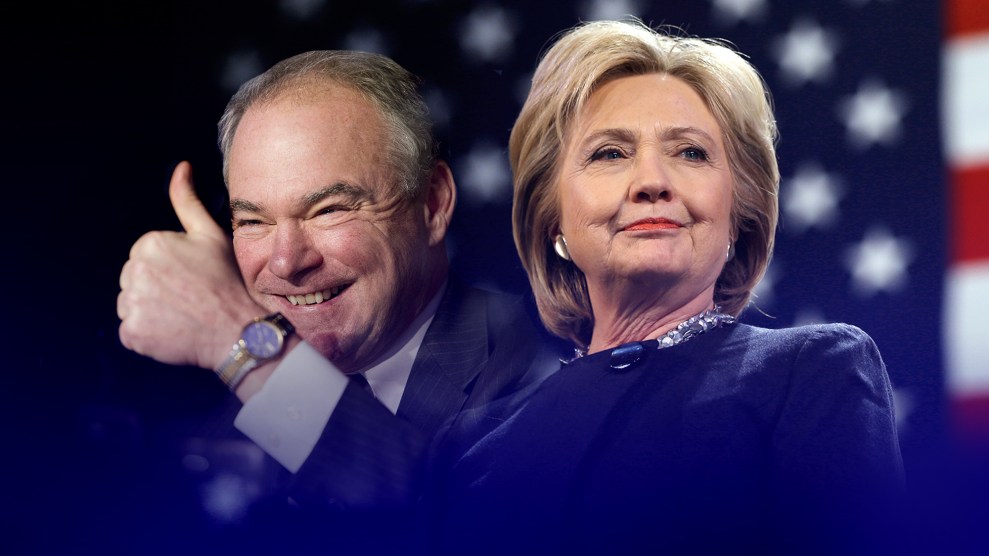

Kaine is a top contender to be Hillary Clinton’s running mate. He’s on a three-person short list receiving full vetting, according to the Associated Press, alongside Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Julián Castro. A former Virginia governor and onetime head of the Democratic National Committee, he has ample executive, legislative, and political experience. He represents a swing state and speaks fluent Spanish—a handy attribute in this year of Trump.

Yet the prospect of Kaine on the ticket has been met with hostility by some on the party’s left wing, many of whom are pining for Warren. Supporters of Bernie Sanders have slammed Kaine for lacking “progressive backbone.” Others, including Kaine himself, have branded him as “boring.” (Kaine’s office declined to make the senator available for this article.)

The latter label helps explain the apparent disconnect between Kaine’s standing as a former progressive crusader and his current status as a target for the left. A reserved, polite Midwesterner, Kaine isn’t temperamentally suited to satisfy liberals who want to see Donald Trump torn apart and his fellow billionaires demonized. Instead, Kaine is a devout Catholic driven by the gospel of social justice and less concerned with the social issues that have become political wedges. Over the course of his career, he has dedicated himself to incremental progress in a red-turned-purple state.

In this way, Kaine bears a political resemblance to the candidate he might join on the Democratic ticket, sharing a political pragmatism focused on inching policy along and eschewing grand gestures. To those who accuse him of insufficient progressivism, he might respond that he is, as Clinton has called herself, “a progressive who gets things done.”

Although Kaine’s political career has taken place entirely in Virginia, his style and beliefs are those of a Midwestern populist. Kaine was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, but grew up mainly in a suburb of Kansas City, where he spent time after school working in his father’s ironworking shop. After graduating from a Jesuit-run high school, Kaine entered the University of Missouri as a journalism major but soon switched to economics because, as he would later tell the Virginian-Pilot, he found journalists to be “a very cynical lot.” He graduated in three years and immediately enrolled at Harvard Law.

A year into law school, he spent a year on a missionary trip to Honduras, where he taught children to weld and gained fluency in Spanish. Back at law school the next year, Kaine met his future wife, Anne Holton, the daughter of former Virginia Gov. A. Linwood Holton. A moderate Republican eventually driven away from the party, A. Linwood Holton worked to desegregate the state’s schools and passed the state’s first fair housing laws. (In 1970, he sent Anne and her siblings to the largely black Richmond public schools, and Kaine keeps on his desk a framed copy of a New York Times front-page photo of the governor escorting Anne’s sister Tayloe to school.) Kaine often lists the elder Holton as his political hero.

Kaine and Anne Holton moved to her home state after they finished law school, and Kaine settled in at a civil litigation firm, where he sought out civil rights cases. He was chairman of Freedom House, a nonprofit that helped homeless Richmond residents, and he sat on the board of Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME), a fair housing nonprofit. When HOME found evidence that minority homeowners in Richmond were being shut out from purchasing insurance by Nationwide—a practice known as redlining—Kaine took on the case, first pro bono and later under a contingent fee arrangement.

Nationwide “pulled all their agents out of African-American neighborhoods,” says Tom Wolf, Kaine’s partner on the case. “They required their agents to go after what they called their ‘target markets,’ and it just so happened that the target markets were all heavily white neighborhoods.” A jury agreed in 1998, levying $100.5 million in damages against Nationwide. Kaine settled with Nationwide a year later for $17.5 million.

Meanwhile, Kaine was quickly rising through the ranks of Richmond politics. He won a seat on Richmond’s city council in 1994, and four years later he became the city’s mayor.

Kaine wasn’t supposed to run for statewide office in 2001, but front-runner Emily Couric—a state senator and sister of television broadcaster Katie Couric—abruptly dropped out of the lieutenant governor’s race, announced that she had pancreatic cancer, and died a few weeks before the election. Kaine, who had been endorsed by Emily Couric, won the Democratic primary and then, by a narrow margin, the general election, running a campaign mostly focused on tying himself to the party’s gubernatorial nominee, Mark Warner. He was widely considered the more liberal member of the ticket and ran on his gun control record as Richmond’s mayor while Warner sought the National Rifle Association’s endorsement.

Virginia law allows governors to serve only one four-year term, so Kaine was gearing up to run for the top job from his first day as lieutenant governor. His better-known opponent in the 2005 race, Republican Attorney General Jerry Kilgore, painted Kaine as a crazed liberal out to expand government and raise taxes. Kilgore also attacked Kaine for his opposition to the death penalty, dating back to his pro bono appeals on behalf of death row inmates, all of which were unsuccessful. Kilgore overshot when he aired an ad claiming that Kaine would have defended Adolf Hitler. Kaine responded with an ad in which he looked directly at the camera and said that while his faith taught him that the death penalty was immoral, he would not let his personal views interfere with the law. (He would later fulfill this promise as governor, overseeing 11 executions.) The campaign’s focus groups found that the ad wiped away concerns, even among proponents of the death penalty, that Kaine was insincere in his promise to carry out capital punishment when needed.

Kaine recognized that, as he put it, “Old Virginny is dead.” He saw that the increasingly liberal cities in the state and the diverse, college-educated suburbs in Northern Virginia offered a path for Democrats to win statewide elections without shying away from progressive views. He built a new Democratic coalition of women and minorities that didn’t need the voters from the conservative rural areas, a strategy that Barack Obama would replicate to win the state in 2008 and 2012. Running explicitly against President George W. Bush’s record, Kaine won the governor’s race a year after Bush had carried Virginia by eight points and Democrats were at a low point nationwide.

The victory instantly made Kaine a Democratic rising star, and he was tapped to deliver the Democratic response to Bush’s 2006 State of the Union speech less than a month after moving into the governor’s office. His address was widely panned as lackluster—remembered mostly for Kaine’s penchant for frequently raising his left eyebrow. His tenure as governor, too, had few defining achievements, beyond a smoking-ban law and a recession-era budget compromise that required him to cut spending across the board when the Republican-led state legislature rejected his calls for tax increases. It was a thin record, but enough to propel him into the presidential campaign conversation.

Kaine came close to serving as Obama’s vice president. “The Virginia governor has emerged as the ‘change’-oriented veep choice for Obama,” The New Republic proclaimed in August 2008. Kaine endorsed Obama early in the Democratic primary, even though Mike Henry, his longtime chief political strategist, was working as Hillary Clinton’s deputy campaign manager. From the start, Kaine and Obama saw each other as compatriots—young politicians who had attended Harvard Law and fought for the rights of poor people, liberal in their views but eager to find common ground.

According to Game Change, John Heilemann and Mark Halperin’s book about the 2008 election, Clinton dismissed Kaine as a potential No. 2, referring to him as a “terrible” choice. But the Virginia governor made it to Obama’s final three, with Sen. Joe Biden and former Sen. Evan Bayh. Kaine passed the vetting process with a clean bill but was axed due to his little foreign policy experience.

But Obama wanted Kaine on his team. Shortly after his election, Obama recruited Kaine to oversee the Democratic National Committee. When Kaine’s term as governor ended in early 2010, he took over the DNC, where his main objectives were protecting the party’s seats in Congress during the 2010 midterms and integrating the president’s campaign apparatus, Organizing for America, and its technological acumen into the party machinery. Kaine’s DNC pushed the president’s agenda and, to the consternation of Democratic leaders in Congress, ran ads in 2010 urging moderate Democrats to support the Affordable Care Act, which wasn’t popular in more conservative areas. Kaine and the DNC were unprepared for the tea party backlash.

Despite outraising the Republican National Committee by more than $30 million, the Democratic Party suffered what Obama would call a “shellacking” in the 2010 elections. The Democrats lost control of the House and were reduced to a slim majority in the Senate, setting the stage for years of Republican obstruction.

But few folks in the Democratic cosmos blamed Kaine. When Virginia Sen. Jim Webb announced in February 2011 that he wouldn’t seek a second term the following year, Democratic leaders began pleading with Kaine to run for the Senate seat. Kaine soon resigned his position at the DNC and entered that race.

Kaine stuck to a script similar to the one he had used during his gubernatorial campaign. He sold himself as a competent manager who could work with Democrats and Republicans and highlighted his support for reproductive rights. He drew a contrast on abortion with his opponent, George Allen, and attacked Allen for refusing to offer his opinion of a Virginia law that forced women to undergo ultrasounds before having an abortion. He rejected Mitt Romney’s 47 percent comment and called for letting the Bush tax cuts on top earners expire. Kaine didn’t shy away from his association with the president, even as Allen gleefully painted Kaine as an Obama lackey. Two years after suffering his biggest political embarrassment, Kaine outperformed Obama and won a Senate seat by a six-point margin.

When he entered the Senate in 2013, Kaine secured seats on the armed services and foreign affairs committees, a rarity for a senator new to the chamber. As the rest of the Senate Democratic caucus focused increasingly on domestic issues, Kaine waded into the details on ISIS and Middle East strategy, fashioning himself as a liberal counterpoint to John McCain or Lindsey Graham.

Last June, Kaine teamed up with Sen. Jeff Flake, an Arizona Republican, to propose a bill that would impose restrictions on the White House in fighting ISIS and require consultation with Congress on strategy. The measure never got a vote, and when Obama requested military authorization without those restrictions, Kaine sounded a skeptical note. “I am concerned about the breadth and vagueness of the US ground troop language and will seek to clarify it,” he said.

This represented a critique from the left. But like Clinton, Kaine has adopted several hawkish foreign policy stances. He has urged Obama to create a no-fly zone in Syria and declared that the administration’s reluctance to establish one “will go down as one of the big mistakes that we’ve made, equivalent to the decision not to engage in humanitarian activity in Rwanda in the 1990s.” He and Clinton have both wavered on the controversial Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, a frequent target of the party’s Sanders-Warren wing. When the Senate voted to grant Obama fast-track authority for the deal last summer, Kaine signed on but said he wouldn’t back the full TPP proposal if it didn’t come paired with a worker retraining measure. “If those assurances are not met, then I will vote against the treaty when it eventually hits the table,” he said.

So far, the main objection to Kaine from progressives has been his stance on reproductive rights. Throughout his political career, he has said he personally opposes abortion but believes Roe v. Wade was the proper legal doctrine and that the government shouldn’t interfere with a woman’s right to choose. It’s a stance similar to Biden’s.

As governor in 2009, Kaine, over the objections of Planned Parenthood and other abortion rights groups, signed into law a bill that created “Choose Life” Virginia license plates, with the proceeds from the sale of the plates going to fund pregnancy crisis enters, which encourage women to seek alternatives to abortion. But Kaine has mostly stood with the advocates of abortion rights. During his time as governor, he slashed all funds for abstinence-only sex education, and he rejected calls to defund Planned Parenthood.

Since he entered the Senate in 2013, Kaine has received perfect marks from Planned Parenthood. Kaine initially called the anti-Planned Parenthood undercover videos promoted last year by the Center for Medical Progress “extremely troubling,” but when Republicans scheduled a vote on defunding the organization, Kaine rejected the measure. When the Supreme Court struck down Texas’ anti-abortion laws last week, Kaine cheered the decision: “I applaud the Supreme Court for seeing the Texas law for what it is—an attempt to effectively ban abortion and undermine a woman’s right to make her own health care choices.”

Still, Kaine’s divergence from the Democratic line on reproductive rights is clearly on his mind as Clinton selects a running mate. Last week, he quietly signed on as a co-sponsor on a major Democratic bill that would block measures making it harder for women to access abortions. And with Clinton running perhaps the most vocally pro-choice presidential campaign in history, reproductive rights advocates likely won’t have much concern about the Democratic ticket.

Unlike in 2008, picking Kaine for the veep slot in 2016 wouldn’t give Clinton a “change” ticket. He’s now a longtime Democratic insider, used to the national media exposure and the high-dollar fundraising that Clinton likely hopes her running mate will bring to the campaign. Sure, he might be the “safe” pick, but for a cautious candidate like Clinton running against a loose-cannon opponent, the reliable, quiet progressive might be the logical choice.