<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/gallery-2892448p1.html">studiostoks</a>/Shutterstock

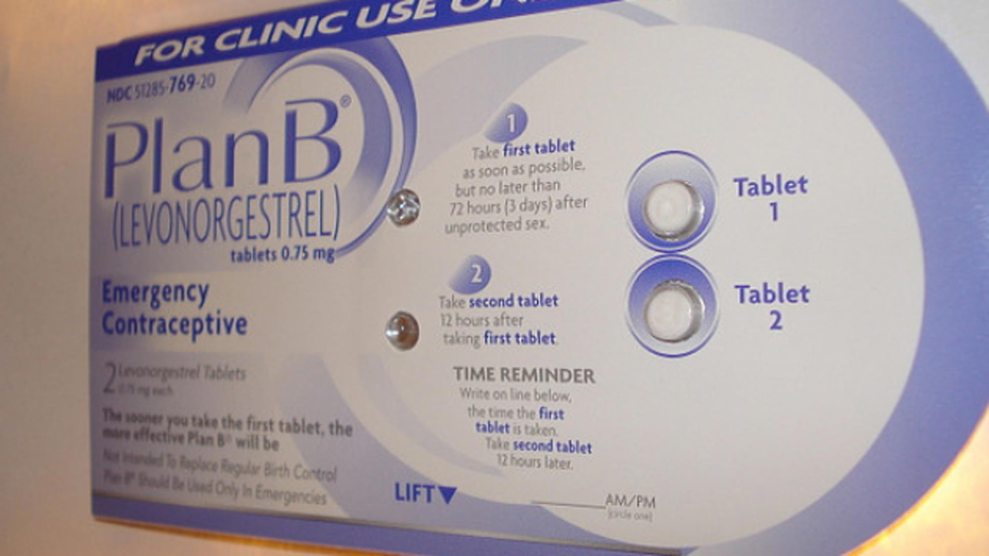

Hormonal contraceptives, such as birth control pills, are safe, up to 94 percent effective, inexpensive, and often inconvenient.

The required daily dose of the medication is not the problem, but the ease and continuity in getting the prescription refilled is, because most insurance companies require a new refill every few months and a new prescription every year or so. Getting that prescription involves a doctor’s appointment. Often that extra step is enough to make women miss a single dose, maybe even a month or more.

Last month, a measure passed the California state Senate by a 29-6 vote that would cut down on some of the hassle of trying to avoid pregnancy for women who take hormonal contraceptives. Senate Bill 999 from state Sen. Fran Pavley authorizes pharmacists to dispense up to a 12-month supply, if the patient asks for it, and requires insurance companies to cover the costs.

“As someone who doesn’t need birth control anymore but remembers what a challenge it was, it’s amazing to me that still today a woman can only get birth control pills that cover 30 to 90 days,” Sen. Pavley said. “This bill would take away not only a logistical inconvenience, but a real challenge to a woman who doesn’t want a baby.”

The bill, which is co-sponsored by Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California, NARAL Pro-Choice California, and the California Family Health Council, aims to reduce the number of unintended pregnancies in the state and cut down medical costs.

“A one-day gap could cause an unintended pregnancy, and the medical and financial consequences of that are enormous,” said Deborah Rotenberg, legal counsel for Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California. “Why not provide women the most robust coverage and access to contraception we can in California?”

Insurance companies raised concerns during the hearings about implementing the legislation. Steffanie Watkins, vice president of health policy for the Association of California Life and Health Insurance Companies, testified that insurers are worried that women would take the opportunity when changing insurance to effectively double up on 12-month supplies, or that women would start a new form of birth control with a yearlong supply, find out there was an undesirable side effect, and then change forms of contraception only to waste months and months of medication.

Jennifer Alley of the California Association of Health Plans said the non-oral contraceptives covered by the bill require refrigeration after four months. She argued that since those contraceptives don’t have a 12-month shelf life—meaning the medication couldn’t remain on a shelf for more than four months but can last in a refrigerator for about two years—they should not be eligible for the coverage. When she was asked to respond to the claim, Sen. Pavley dryly replied that women are “fully capable of placing a product in the refrigerator.”

This isn’t California’s first attempt at expanding access to contraception. In 2013, Gov. Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 493 into law, allowing pharmacists to prescribe oral (the pill), vaginal (the ring), transdermal (the patch), and Depo-Provera injection birth control methods without involving a doctor.

The passage of that measure did not mean that California women immediately were able to access birth control. One reason is that the law gave both insurance companies and pharmacies a loophole by not making the service mandatory. The 2013 law didn’t go into effect until April 8 this year, after the state finished finalizing regulations. Spokespeople from Walgreens and Rite-Aid told NPR that they do not provide the pills or the patch without a physician’s prescription yet; a Walgreens spokesperson added that they are “assessing” the law’s requirements. Interest in participating in the new law appears to be lukewarm, at best. The NPR report found that at the California Pharmacists Association annual meeting last month, only 150 people took the training workshop to provide birth control. There are 29,000 pharmacists registered in California.

Another complication with the 2013 law’s implementation is that most insurance providers won’t reimburse pharmacists for a woman’s birth control consultation as they do for gynecologists, so there’s no financial incentive for a pharmacist to take on the extra work. But in Oregon, a state that passed similar legislation in June allowing pharmacists to dispense birth control, Medicaid will issue a $35 reimbursement to a pharmacist for the service.

But Pavley says she is confident that her bill won’t encounter the same issues as the 2013 law—hers is a mandate, and the insurance companies will have to comply if it passes into law. And the numbers are on her side.

A 2011 University of California-San Francisco study found that unintended pregnancy rates and abortions plummeted when women had access to a 12-month supply of birth control. The researchers observed women who were enrolled in Family PACT, a California family-planning program. They found a 30 percent reduction in the odds of unplanned pregnancy, and a 46 percent decrease in the abortion rate.

Diana Greene Foster, the lead author in the UCSF study, said her findings were consistent with other work she’s done around reproductive health.

“In a[nother] study I did among women in abortion clinics, one in five reported that they had unprotected sex because they ran out of the birth control method they were using. A similar percentage of women who had experienced unprotected sex but never had an abortion also reported that they had had unprotected sex specifically because they had run out of birth control,” Foster said. “Most women have more pressing demands on their time than waiting to fill a prescription every month.”

Similar efforts are underway in Hawaii, New York, Washington, Wisconsin and Colorado. The District of Columbia and Oregon have already passed laws that allow women to receive a 12-month supply of birth control. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists also recommend annual dispensing.

Pavley is frustrated with the insurance groups’ resistance and says their focus is on “the dollars and cents” of it. But she also notes, “I remember the horror stories of unplanned pregnancies, and we’ve calculated the amount of money it would save in unintended pregnancies and abortions.” In the long run, the measure would save the state money in health care costs. In a separate analysis of SB 999’s potential, the California Health Benefits Review Program found that the reduction in unintended pregnancies and doctor visits would result in about $42.8 million in savings for the state in its first year of existence.

“Hormonal contraception is safe, but the barriers we provide for women attempting to avoid unintended pregnancy are unnecessary,” testified Dr. Mitchell Creinin, chief of family planning for the University of California-Davis Health System’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology during the committee hearing. “Studies in California have proven that we are harming women and families and increasing health care costs for the state as well as for private insurers by limiting supply of those contraceptives, for which proper use is very time sensitive.”