In 2011, Don Foss, perhaps the richest used-car salesman in the history of the world, commissioned a half-hour film about himself and posted it to YouTube. The Don Foss Story opens with one of his TV ads from the 1970s, ads for which Foss hired an actor to portray him. (The real Foss, who is portly and balding, says he might have played himself “if I looked like Robert Redford.”) At the ad’s conclusion, we meet the film’s narrator: “Today I’m going to guide you through the story of a truly remarkable man,” he intones before lobbing the auto billionaire his first softball: “Don, your story pretty much epitomizes the great American Dream. I’m sure everybody wants to know how you did it.”

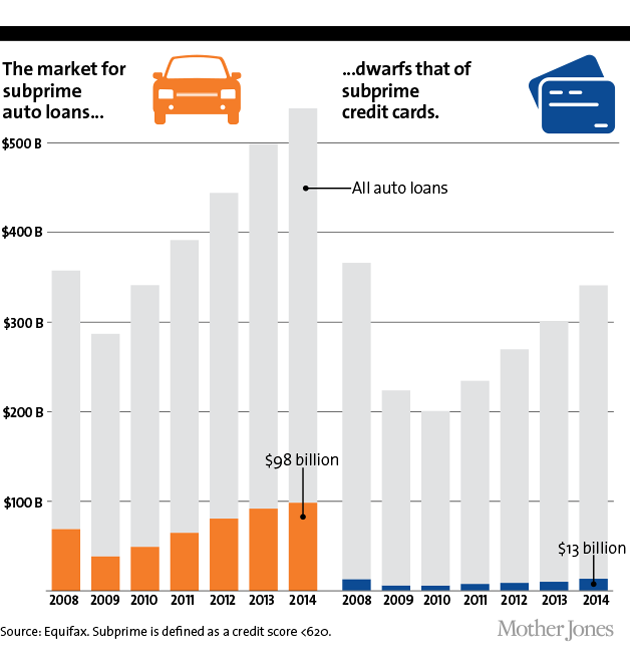

What Foss did was practically invent the subprime car loan, a market that today exceeds $100 billion a year. First as a dealer, and later as the founder of an auto-financing company called Credit Acceptance, he was “really the first to see all the money to be made arranging the financing for cars that would otherwise end up in the crusher, and selling them in poor neighborhoods,” says a longtime auto industry consultant.

The Don Foss Story casts things a bit differently. It includes a lot of talk about the nobility of extending credit to people no one else would lend to. If not for Credit Acceptance and its imitators, how would people make it to and from work, shuttle the kids to school, or take Mom to her dialysis appointments? By 1995, when the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page story on this “corner of the lending world J.P. Morgan would not recognize,” Foss’ personal stake in Credit Acceptance was worth $550 million. The company’s stock was trading at $21 a share then. Today the price hovers around $200.

Virtually all of this growth has taken place since 2008—not despite the Great Recession, but largely because of it. When millions of Americans lost homes to foreclosure and millions more lost their jobs, it created a vast new reservoir of customers with tarnished credit and little cash. The amount of money loaned to these subprime borrowers—who now account for nearly a quarter of all auto loans—has more than doubled since 2009, the New York Fed reports. And because car loans, like mortgages, can be bundled and peddled to Wall Street investors, subprime auto bonds have emerged as an attractive replacement for the disgraced subprime mortgage bonds. In 2009, auto financiers sold about $3 billion worth of subprime auto bonds through the securities markets. By 2014, that number was $22 billion.

While the subprime auto market is nowhere near large enough to bring down the economy, there are unmistakable parallels to the mortgage debacle. Delinquencies and repossessions are on the rise industry-wide, and there have been reports of falsified loan applications. At least eight banks have come under scrutiny for allegedly jacking up interest rates on black and Latino car buyers. Big players including Ally Financial and Fifth Third Bank (America’s ninth-largest bank) recently paid out nearly $200 million to settle such accusations. “Auto loans are now the most troubled consumer financial product,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) noted last spring. “The market is now thick with loose underwriting standards, predatory and discriminatory lending practices, and increasing repossessions.”

It is the real Don Foss story—the sometimes remarkable, often disturbing tale of a subprime auto-lending pioneer—that helps us understand how we got here.

In 1967, when he was 22 years old, Foss opened his first used-car lot on a Detroit street thick with dealerships. At the time, automakers like General Motors and Ford were loaning money only to customers with solid credit, and the banks wouldn’t extend loans in the city’s black neighborhoods at all. From the start, Foss, whose father was also a used-car dealer, catered to the working poor and others with less-than-stellar credit. His secret was to break even on the customer’s down payment and trade-in, and then grow rich off the monthly payments and court judgments against those customers who defaulted.

He soon opened more lots in the Detroit area and hired his TV stand-in to portray him as a man suffering from “negaphobia,” rendering him incapable of saying no, even to someone with terrible credit. In the ad that kicks off The Don Foss Story, the fake Foss sits behind a desk looking like a serious businessman—until he pushes back his chair to reveal pajama bottoms and oversize clown shoes. Gospel singers chime in: “Don Foss puts you in the driver seat; take a Don Foss ride down easy street.”

Five years after opening his first lot, Foss launched Credit Acceptance. The new company handled financing and collections for the 17 dealerships he would eventually open in six states. The amount of interest he could legally charge customers was limited only by the laws of the state where the car was sold—when there was any limit at all. “I was the friendly car salesman one week,” Foss told the host of his biopic, “and the following weeks I was the money-grubbing bill collector.” In 1989, Credit Acceptance began promoting itself as a national lender eager to work with other dealers who sold to people on the margins.

Take Keith McCluskey, who before Foss came along moved maybe 15 used cars a month at McCluskey Chevrolet in Cincinnati. That’s because big auto lenders like General Motors Acceptance Corp. rejected most of his low-income customers. Then he received a postcard from Credit Acceptance promising to finance practically anyone. In The Don Foss Story, McCluskey deems this probably the most significant moment of his business life. Credit Acceptance would lend to welfare recipients, teenagers, and even people who had recently declared bankruptcy. With Foss’ help, McCluskey says, he was soon running the largest Chevy dealership in the state.

Foss took Credit Acceptance public in 1992. It was around then that Ohio lawyer Ron Burdge, in the process of suing a used-car dealer, obtained a copy of Credit Acceptance’s corporate manual and realized, with a mix of horror and awe, that “they had created this remarkable system for taking every last dime from their customers.” Of Credit Acceptance’s nearly 300 employees, roughly 200 were in collections, and the company pursued delinquent borrowers with machinelike efficiency. If that didn’t work, a company lawyer would sue the customers for damages—including additional interest and legal fees—and then go after their wages in states that allowed it. “They brought everything to a totally new level,” said Burdge, who used what he learned in subsequent lawsuits against the company.

Illustration by Ross MacDonald

Three years later, when a Wall Street Journal reporter arrived in Michigan to profile Foss and his business, it wasn’t uncommon to find customers saddled with interest rates as high as 30 percent. Borrowers typically paid twice what the car had cost the dealer, the paper reported, and often those vehicles didn’t outlast the loans that financed them. Eventually, Credit Acceptance and other subprime lenders would even start requiring borrowers to install starter kill switches that allowed the companies to incapacitate their vehicles from afar, “pretty much guaranteeing that the car loan is the first one people pay every month,” a former Ford finance manager told me. Credit Acceptance now finances sales for thousands of used-car lots across the United States, and Foss’ success has inspired any number of imitators: Capital One, Santander, and Wells Fargo are just a few of the big players that piled into the business of extending car loans to desperate people at borderline usurious rates. “The thing I didn’t realize about going public is that you tell everybody how your business works,” Foss cracked in one interview.

Not all of the scrutiny came from competitors. Foss was about to have a potentially bigger problem on his hands, courtesy of a couple of Kansas City lawyers. Bernard Brown was a solo practitioner in his early 40s who specialized in auto fraud cases. Dale Irwin, six years Brown’s senior, was a former Legal Aid attorney who worked for a small firm specializing in consumer law. In 1996, they teamed up to file a class-action suit against Credit Acceptance on behalf of 14,000 Missourians, accusing Foss’ company of a host of infractions—from repossessing cars with improper notice to charging working-poor customers hundreds to thousands of dollars a pop in bogus fees and interest overcharges.

The lead plaintiff was Marvin Fielder, a Kansas City liquor store clerk and married father of four. The dealer had told Fielder the total price on the 1985 Honda Prelude he was buying was $5,700, but according to the complaint, when Fielder read the fine print that night, he discovered he was being charged more than $7,000. He went back to the lot the next day, but the dealer refused to give him the original deal, so he returned the Honda. Credit Acceptance, which had financed the sale, took possession of the car and resold it. It then sued Fielder for the full loan amount—which it claimed he owed even though he’d held the car for less than 24 hours—plus additional charges. “They were total cowboys, making things up as they were going,” Brown said.

In legal briefs, Credit Acceptance countered that Fielder and the other plaintiffs had been presented with the terms in writing and had affixed their signatures to a legally binding contract. No one had held a gun to their heads. Amid the back and forth, Irwin and Brown obtained documents showing that in the mid-’90s nearly 80 percent of Credit Acceptance’s Missouri customers were more than 90 days delinquent—an astonishingly high number. (The current 90-day delinquency rate for specialized auto financiers is about 5 percent.) Many of those 14,000 plaintiffs had been sued individually by Credit Acceptance and hit with court judgments inflated, the lawyers charged, by improper fees. “You’d look at one of these cases and it was like a law school test where the professor had you look through the paperwork to see how many violations you find,” Irwin said. The most obvious: charging past-due customers a higher interest rate than the contract stipulated.

It took more than a decade of legal wrangling, but Credit Acceptance finally agreed to pay a $12.5 million settlement and forgive about $75 million in delinquent loans. The deal included $5,000 for each of the six named plaintiffs, while Brown and Irwin were paid $3 million apiece. The company also agreed to three years of court-sanctioned monitoring by the lawyers. “It was a good day after 11 years,” Brown said.

The judgment was a speed bump for Credit Acceptance, but the industry rolled merrily along. When the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was established in the wake of the 2008 crash, the National Automobile Dealers Association spent millions of dollars lobbying Congress to be carved out from the bureau’s oversight; during the 2009-10 cycle, dealers and their PACs spent another $8 million on direct political contributions, mostly to Republicans. For auto financiers, which are regulated by the CFPB, the dealer carve-out was a valuable gift. “It set up a situation where the lenders are saying, ‘Don’t hold us responsible; it’s the dealers who are making all the decisions,'” explained Chris Kukla, a senior vice president at the Center for Responsible Lending. “But it’s the lenders who are setting the conditions.”

Buying and financing a car take place as a single transaction inside a dealership, Kukla added, and splitting oversight among multiple agencies—dealers are regulated by state agencies and the Federal Trade Commission—”makes it that much harder for regulators to do their job.” Last year, Reps. Frank Guinta (R-N.H.) and Ed Perlmutter (D-Colo.) introduced a bill that would limit the CFPB’s ability to pursue dealers who target black and Latino buyers with discriminatory interest rates—88 Democrats supported the bill, which passed the House in November on a 332-96 vote.

Those calling for less monitoring of car dealers should consider the saga of Carrie Peel, the client at the center of Brown and Irwin’s next big case. Peel worked full time as a pricing manager at the Cargo Largo, a discount store in Independence, Missouri. She made less than $20,000 a year. Philip, her husband, earned even less as a loading-dock worker. They had four kids and a credit score in the low 500s—deep subprime. But with gas prices topping $4 a gallon, the Peels could no longer afford to fill up their Chevy Suburban. On a sweltering Saturday in July 2008, they went shopping for a replacement at the Car Time lot on Highway 24, a forlorn stretch consisting of payday lenders, a pawn shop, and a Do Over Thrift Shop. With her credit score, Peel recalls, “it’s not like I had any other options.”

According to court documents, the couple ended up paying $12,450 for a four-year-old Ford Taurus, about $5,000 more than the Black Book value—and that didn’t include the extras, such as a $209 charge for “fees to public officials.” (It actually cost the dealer about $10 to file the required paperwork with the state.) The Peels also let the salesman talk them into an extended warranty for $1,380. Minus their $1,000 down payment and the $2,500 that Car Time offered for the Suburban, they were left with a balance of $10,960, to be financed by Credit Acceptance. The interest rate—24 percent—was triple what they would have paid with good credit, and it amounted to an additional $6,620 in payments over the life of the loan. They would pay $17,580 all told, but “this was going to be my chance to build up our credit so we’d never have to pay a rate like that again,” Peel says.

Carrie Peel is in her 30s, a cheery woman with frosted blond hair who now works as a bartender. She has no complaints about the Taurus—she describes it as the nicest vehicle her family ever owned. But years later, sitting in Brown’s office and reliving the details of the deal she signed at Car Time, Peel grows angry with a system she sees as rigged against those on the wrong side of the economic divide. The dealer charged way too much for a car that had cost him less than $7,000. And she felt coerced into paying $420 for Guaranteed Asset Protection, or GAP insurance, an optional add-on that Peel says was presented as a condition of the loan—a common practice.

“If a salesman was telling the truth when selling GAP insurance,” Irwin says, “he would have said, ‘Ms. Peel, we’ve screwed you over horribly on this deal. We’ve charged you twice what this car is actually worth and then inflated what you’re going to pay us with exorbitant interest rates, made-up fees, and an extended warranty that’s never going to cover what you think it should. And because you’re paying so much more for this car than it’s worth, to protect us from the fact that we cheated you, we’re going to make you buy GAP insurance to protect our investment should anything happen to this car.'”

A few weeks after they bought the Taurus, the Peels realized that the dealer had never sent them a copy of the title they needed to get the car registered. They drove back to the dealership and found the lot deserted—Car Time had gone belly-up. It wasn’t hard for Irwin and Brown to piece together what had happened: To pay for his vehicles, a used-car dealer typically borrows money from a “floorplan bank” that keeps the titles as collateral. When a vehicle is sold, the dealer is supposed to repay the bank, which then hands over the title. But when business is bad, an unscrupulous seller may hang onto that money in a futile attempt to stay afloat. They “rob Peter to pay Paul, hoping to get back on their feet,” Brown explained. Post-financial crisis, Irwin added, “there’s definitely been a spike in dealerships playing these kinds of games.”

Credit Acceptance had gotten stiffed right along with the Peels—and presumably some of the 31 other Car Time customers who bought cars around that time—but instead of going after the real culprit, Foss’ company put its customers on the hook. It insisted that Peel still owed the full amount—principal and interest—laid out in the contract. So for two years the family faithfully scraped together $345 a month to make payments on a car they couldn’t legally drive. Peel tried tracking down the owner of Car Time herself. She made several trips to the DMV and even managed to locate the previous titleholder (another finance company). She complained to various consumer affairs agencies, including the state attorney general’s office. And she repeatedly contacted Credit Acceptance, whose logo and name were all over her paperwork. “I call and call and they tell me, ‘We have no idea where the title is,'” Peel said. She begged the reps to help her find Car Time’s owner, but “it was always, ‘It’s not our problem; it’s between you and the dealer; you still have to pay us.'”

When she threatened to stop paying, she said, the person on the phone would remind her of the starter kill switch by which the company could disable her car if she missed a payment—she never did. A court would later determine that Credit Acceptance knew Car Time’s floorplan bank probably held the title but neglected to share that information with Peel, who was twice pulled over by the police for driving without valid registration. The first officer let her off with a warning. The second one slapped her with a $140 ticket. Feeling wronged, she refused to pay. A judge put out a bench warrant for her arrest.

Credit Acceptance’s own records show that Peel spoke to 111 separate people in its call center over two years. Never once was she granted access to a supervisor, despite her pleas and the occasional promise of a callback. She felt helpless, she told me. Without a title, she couldn’t drive the car legally and she couldn’t sell it. And with her credit tied up in the Taurus, it’s not like anyone would loan her the money for another car. “I’m very, very polite,” she said. “I come from a good family. But I got pissed off. I got a little crazy a couple of times.”

One of those times came at work. “I was screaming, ‘I want a supervisor to call me back right now,'” Peel said. “I went damn near psychotic. People are looking at me. I’m crying.” She told the Credit Acceptance rep that she was done paying, knowing full well that if she stopped, she’d end up with a repo on her credit report. “I was trying to fix my credit, and here these people are telling me they’re going to ruin it if I don’t do what they say,” Peel said.

Not long after her rant, Peel lost her job at the discount center. The saving grace was that now she and Philip qualified for free legal help. A Legal Aid lawyer referred her to Irwin, who got Brown involved. “Nobody could say she did anything wrong,” Brown said. “She had been badly cheated by the dealer, and then Credit Acceptance abuses her more, just to pile up more profits.”

“Changing Lives Since 1972,” reads a Credit Acceptance tagline. “Everyone deserves a second chance,” says another. For years I’ve been leaving messages with the company in the hope of talking with Foss. Since the 2008 crash, I’ve been fascinated by businesses catering to people on the margins, and by this depressingly visionary man who saw the untold billions to be made selling cars to people whom conventional lenders deemed too risky. I’ve spent time with the pioneers of payday lending, tax refund anticipation loans, and the rent-to-own business, but I’ve never received so much as a return phone call from Foss’ company—for this or any other story. “Credit Acceptance believes that individuals, if given the opportunity to establish or re-establish a positive credit history, will take advantage of that opportunity,” notes the corporate website. Don’t the working poor deserve the same access to credit as everyone else, even if it costs them more?

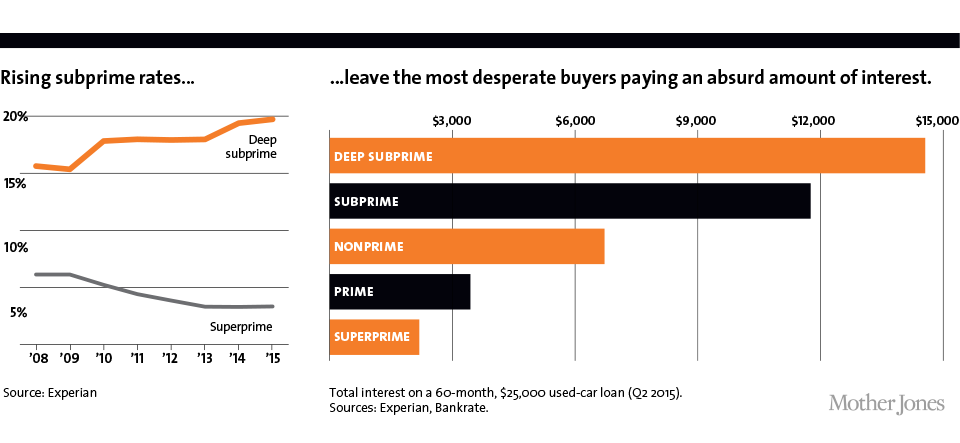

Yet Credit Acceptance makes its loans knowing that a large portion of its customers won’t have the happy endings advertised in the promotional materials. The company operates on the assumption that it will collect only about 70 percent of the money it lends out—which means it will end up repossessing an awful lot of cars and suing those customers for the balance. As Wall Street banks clamored for more securities built on subprime auto debt, Credit Acceptance pumped out ever more paper, boosting loan volume by 23 percent in 2010 and 30 percent in 2011. (Growth has been slower in subsequent years due to increased competition, notes the company’s 2014 annual report.) In the meantime, subprime lenders have boosted their average interest rate on used cars from 16 percent to nearly 20 percent annually, guaranteeing that more customers will default and end up with punitive court judgments and garnished wages.

Gary J. Pieples sees plenty of those folks at the free consumer clinic he runs at the Syracuse University College of Law. Half of his active cases fall into the category of improper auto-lending practices, Pieples told me, and most involve Credit Acceptance. It’s easy to blame the “fly-by-night dealers selling crappy cars for too much money to people who don’t have any other option,” he said, “but the dealers couldn’t be doing what they’re doing without money from outfits like Credit Acceptance.”

After two years of faithful payments to Credit Acceptance, Carrie Peel’s credit score did, in fact, improve. In mid-2010, her family was able to secure a loan at a much lower rate and buy a used minivan. Around the same time, on the advice of her lawyers, she stopped making payments on the Taurus and sued Credit Acceptance for deceptive practices. Irwin informed the company that his client had no claim on the car, but that if the lender did, here was the address where it could be picked up. Credit Acceptance countersued, claiming that Peel owed restitution for putting 16,000 miles on the vehicle. The company also reported her account as more than 90 days delinquent, which dragged her credit score down to 482. “They were sending a message: ‘There’s a price to taking us on,'” Brown said.

Carrie A. Peel v. Credit Acceptance Corp. (Text)

So Peel’s lawyers made an offer: If Credit Acceptance would pay her $30,000 and provide similar restitution to any borrower in her situation, she’d settle. The company said no. At the subsequent trial, in 2011, jurors found that Credit Acceptance had violated state law; they awarded Peel $1.1 million in compensation and damages, to be split with her lawyers. A Missouri appeals court upheld the verdict. The company “used its superior position to misrepresent to Peel that she owed payments under a void sales contract,” Judge Gary D. Witt wrote, adding that the company’s conduct was “sufficiently reprehensible” to justify the large sum.

Last year, Credit Acceptance revealed in shareholder filings that it was under investigation by the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission for questionable practices related to subprime lending. GM Financial, Santander Consumer USA, and other big subprime players have also come under government scrutiny. But the regulators are up against powerful market forces.

The company Foss built now boasts a profit margin nearly double that of Google, and the kind of growth curve—a $10,000 investment at the end of 2008 would today be worth more than $150,000—that leaves Wall Street drooling. In 2010, the year Peel sued Credit Acceptance, General Motors paid $3.5 billion to acquire the Foss rival AmeriCredit Corp., which became GM Financial. That same year, a private-equity firm called Fortress Investment Group paid $124 million for a controlling interest in the subprime auto lender Springleaf Holdings (an investment now worth an estimated $3.5 billion).

The following year, private-equity giant Blackstone bought another subprime auto lender, and three private-equity behemoths—Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, Centerbridge Partners, and Warburg Pincus—purchased a 25 percent stake in Santander Consumer USA, created after Spain’s Banco SantanÂder acquired yet another Foss rival. These investors more than doubled their money when the new company went public in early 2014. “When you say Santander and Credit Acceptance, you’re talking about companies 1 and 1A, as far as the crappy things they do to people,” said the Center for Responsible Lending’s Kukla.

Even the sharing economy has jumped into the game. At the end of 2013, Uber—whose growing labor force now exceeds 400,000 “active” drivers—partnered with Santander and other subprime lenders in a bid to further expand its pool of freelance drivers. The company abruptly ended its relationship with Santander this past July, but it still works with other lenders, peddling high-interest car leases to prospective Uber drivers with “poor credit or no credit history.”

All of this activity has Bernard Brown worried. He’s convinced that prosecutors and regulators aren’t moving aggressively enough to rein in the dealers and lenders. He’s also worried that guys like him and Irwin are becoming a dying breed. In recent years, auto financiers—like much of corporate America—have added clauses to their contracts that route aggrieved customers to arbitration firms chosen by the lenders and bar them from joining together in class-action lawsuits.

Pity the poor consumer lawyers, you might say—these guys who rake in millions while their plaintiffs get a few grand each. And yet, how many ripped-off customers have the ability to fly solo in court, or in arbitration, against a powerful corporation? In a world of slow-moving regulatory agencies, a class-action lawsuit functions as both a subprime buyer’s last line of defense and a powerful check on corporate misbehavior.

Now that class actions are largely off the table, lawyers are leaving the field in droves. The once-annual National Association of Consumer Advocates‘ auto fraud conference is now held every other year because there are only half as many attorneys pursuing auto fraud as there were a decade ago. Even with all the reverse redlining, the dishonest dealer tactics, and the booming sales of high-priced loans to millions of Americans who are barely getting by, said Ira Rheingold, the association’s executive director, “this is an area of the law that is actually diminishing.”

Perhaps the biggest scandal of all, though, is that we’ve come to accept as normal the crippling rates auto financiers can legally impose on people. Subprime lenders routinely milk their customers for close to the maximum amount a given state allows. Even with her Taurus as collateral that could be reclaimed and sold, the company Foss founded charged Carrie Peel 24 percent interest—about what she’d have paid for a straight cash advance on a subprime credit card. It charged that much simply because it could. Were it not for the dealer’s title games, the Peels would have had no recourse. They would have been just one more working-class family saddled with a very expensive ride.

This article was reported with the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute, where Gary Rivlin is a fellow.