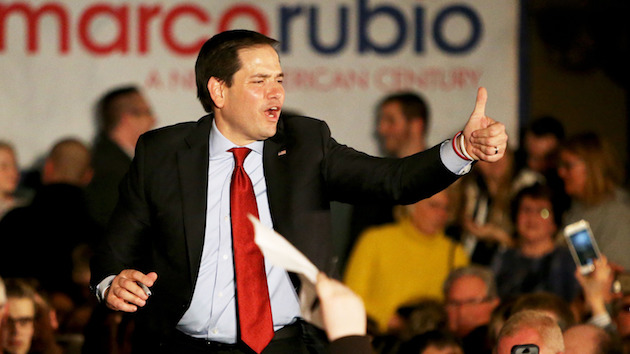

David Joles/ZUMA

Last week’s Republican presidential debate had just begun when Marco Rubio launched into his first of many broadsides against front-runner Donald Trump for the hiring practices in his real estate empire. “Even today,” the senator from Florida said, “we saw a report in one of the newspapers that Donald, you’ve hired a significant number of people from other countries to take jobs that Americans could have filled.” He repeated the attack again on the eve of Super Tuesday this week, saying at a rally in Atlanta that Trump had recently hired foreign workers in Florida. “I know Americans are qualified to do those jobs, because those are the jobs my parents did, working in a hotel,” Rubio said.

The critique didn’t appear to have much of an effect: Trump dominated the primaries and caucuses on Tuesday, winning seven states while Rubio came away with just one. And Rubio might want to think twice before employing that line of attack again, since he’s as vulnerable to it as anyone.

It’s not that Rubio has staffed his Senate office with cheap foreign labor. (As Trump retorted during the debate last week, “I’ve hired tens of thousands of people over at my job. You’ve hired nobody.”) But Rubio has been unwavering in his support for guest worker visas that some companies exploit to replace American workers with foreign ones. As Rubio continues to hammer Trump for hiring foreign workers to do jobs that Americans can do, he is actually highlighting one of his own weaknesses as he faces the populist, nationalist frenzy that Trump has whipped up.

Rubio’s work on the Senate’s “Gang of Eight” immigration bill in 2013 has been a stumbling block throughout his campaign for the Republican presidential nomination because of his support for the bill’s path to citizenship or, as the right wing calls it, “amnesty.” Less discussed is the fact that Rubio led the charge to expand a business-friendly guest worker visa program known as H-1B. He even brought in an old friend who was a partner at a corporate immigration firm—and whose clients stood to benefit from the guest worker program—to lead his office’s work on the bill.

Under the federal H-1B program, which began in 1990, the government provides a set number of temporary visas for foreigners to work in the United States. The visas are intended for high-skilled workers whom companies need in order to compete, and they’re popular in the technology sector and among big businesses. But critics say the program is prone to abuse by companies seeking cheaper sources of labor. Offshore outsourcing firms dominate the H-1B game, and many H-1B visa holders take their skills back to their home countries, with just a small fraction remaining in the United States and applying to become permanent residents. India’s former commerce minister once called H-1B the “outsourcing visa.”

Rubio’s recent attacks on Trump focus on low-skilled labor rather than the high-skilled workers who are eligible for H-1B visas. But the criticism Rubio is now lobbing at Trump uses the same basic logic as the critiques of the H-1B program that Rubio has fought hard to expand—that foreign workers are taking away American jobs.

Rubio’s stance on H-1B puts him at odds with his leading opponents. In the heat of the presidential campaign, Ted Cruz reversed his support for a politically toxic H-1B expansion. Trump, in spite of his questionable hiring practices, actually included reforms to the H-1B program in his six-page immigration reform plan released last summer that would encourage firms to hire American workers—reforms that Rubio pushed back against during the Gang of Eight negotiations.

For the sake of efficiency, and to allow senators to work on their pet issues, each of the Gang of Eight members ended up focusing primarily on one aspect of the bill. Republican Sens. John McCain and Jeff Flake of Arizona, for example, took on the issue of border security. Rubio took the lead on H-1B visas.

Much of the work on the bill was hammered out by the senators’ staffers. Instead of using one of his own staffers to negotiate on his behalf, as the other senators did, Rubio brought in a longtime friend from Miami, Enrique Gonzalez. Before stepping aside to work on the Gang of Eight bill, Gonzalez had been an attorney at one of the nation’s largest immigration firms, which helps corporations bring in foreign workers through the H-1B program.

Heading into the negotiations, Rubio and Gonzalez were firmly aligned with the tech industry, which supported an H-1B expansion. (Tech executives can play a big role in financing political campaigns; one of them, the world’s fifth-richest person, is a top donor to the effort to elect Rubio.) According to people with knowledge of the negotiations, Gonzalez pushed for more H-1B visas while resisting measures to discourage companies from using guest workers instead of American ones. The main opposition came from Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), who had been pushing legislation since 2007 to reform H-1B in order to rein in abuse.

“So the question was, was there a compromise that we were going to be able to get that would raise the number of visas but be more protective of American workers?” explained one Democratic staffer involved in the negotiations. At the start, the negotiations included strong new worker protections that pleased Durbin and his allies in the labor movement. But after each round of negotiations, the bill became “less and less American-worker friendly.”

Rubio was adamant that the bill suit the needs of the tech industry. “All Sen. Rubio ever said was, we need tech to be really behind this,” recalled one staffer. Meanwhile, the other Republican senators working on the bill “very clearly deferred to Rubio and his staffer,” according to another staffer. To show their appreciation, tech executives ran an ad in support of Rubio’s work on the bill while it was being debated in the Senate.

By the time the bill had passed the Senate, negotiations over H-1B visas had taken more time than any other piece of the bill, including the higher-profile path to citizenship and border security provisions. And the tech industry had largely won the day. (The bill later stalled when the more conservative House leadership declined to take it up.)

According to a labor union official familiar with the negotiations, when Gonzalez came on board, “the tenor of the negotiations really changed, and the final bill ended up losing a lot of the advances we had made before Enrique came on board.” But a staffer involved in the negotiations argues that Gonzalez was simply doing what was needed to achieve Rubio’s goal of winning tech industry support. “He was just the mouthpiece for what would have just been expressed by some other mouthpiece,” the staffer says. The Rubio campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Gonzalez’s role in the negotiations raised eyebrows because of his previous job as an immigration lawyer. Gonzalez said he severed all ties with his firm in order to work for Rubio, and Rubio’s office took extra steps to make sure there were no ethics violations. But Gonzalez still advocated provisions that would benefit the industries that he used to represent. By the fall of 2013, just a few months after the bill had passed the Senate, he had returned to his old firm.

The day before the Gang of Eight unveiled its bill, Gonzalez emailed new language to at least one other negotiator for two new provisions he wanted to insert into the bill at the last minute. The language, which made it into the final bill, would have made it easier for both utility companies and cruise liners to hire foreign workers on a temporary basis—and, as CNN reported, would have helped his former clients, which included the utility Florida Power & Light and the cruise line Carnival. “It was clear it was very, very important to him to get it into the bill,” recalled one of the staffers who was in the final staff meeting.

Gonzalez has denied any conflict of interest in his work on the bill. But if Rubio continues hammering Trump for bringing in foreign labor, he may not be able to dodge his own record of advocacy for helping companies hire workers from abroad.