Chris Carlson/AP

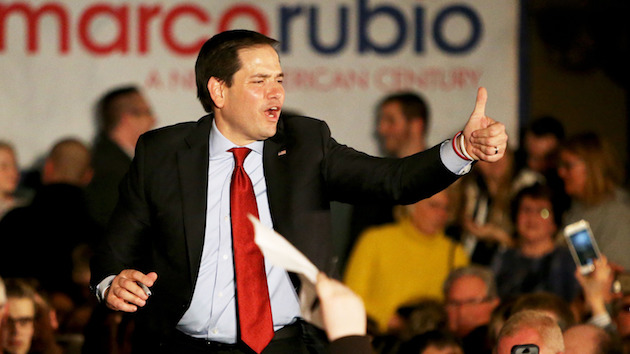

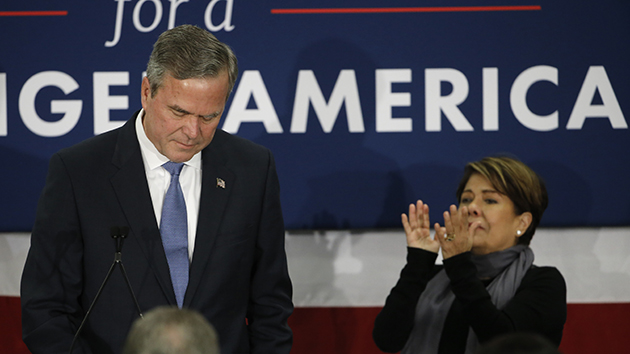

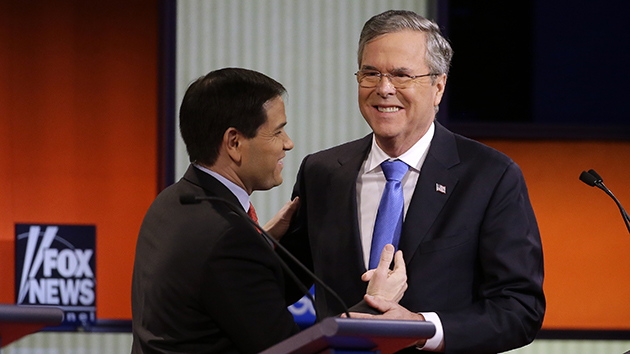

The day before the South Carolina primary, Politico Magazine ran a story titled “How Marco Slew His ‘Mentor.'” Sure enough, Jeb Bush came in a dismal fourth place in South Carolina, behind Marco Rubio’s second-place finish, and he dropped out of the race that night. But this coming Tuesday, Bush may have the last laugh.

Rubio’s flickering campaign hopes depend entirely on Tuesday’s primary in Florida, which both Rubio and Bush call home. Along with the other contests on Tuesday, it’s the first winner-take-all primary of the race, with the top vote-getter claiming the state’s 99 delegates and everyone else leaving empty-handed. If Rubio loses there to Donald Trump, his campaign is effectively over. Polls suggest a tightening race, and if it does end up close, it could very well be Bush who throws the contest to Trump.

When Bush dropped out of the race on February 20, absentee and mail-in voters in Florida had already received their ballots, and some 300,000 Republicans had already filled them out and returned them. According to one veteran Florida pollster, that’s likely to include more than enough Bush votes to topple his former protégé if Rubio and Trump find themselves within a percentage point or two of each other on Tuesday.

“The most interesting story of the year in Florida will be if Marco comes within 25,000 votes of Trump,” says Steven Vancore, president of the market research group ClearView Research. That, he says, would mean Rubio likely could have won Florida if Bush had dropped out of the race earlier.

Here’s his explanation: Bush ended his campaign on the night of February 20. By the time ballots mailed by February 20 reached the county election supervisors, nearly 304,000 Republicans’ primary ballots had been collected. At the time Bush dropped out, he was polling around 9 percent in Florida. That’s about 27,000 votes for Bush. Of course, Bush could have underperformed his poll numbers, particularly if some of his supporters were holding off on voting as they waited to see if he would stay in the race. On the other hand, Bush supporters were likely regular, seasoned voters—just the type to send their ballots in early.

Twenty-seven thousand voters represent less than 1.5 percent of likely Republican voters in Florida, where about 2 million people are expected to vote in the GOP primary. On the other hand, if there’s a state that tends to defy the odds and select winners by razor-thin margins, it’s Florida.

While not every vote for Bush would have gone to Rubio, it’s likely Rubio would have gotten a substantial share. Before he dropped out, Bush played the role of Trump’s greatest critic, and many of Bush’s supporters are likely in the #NeverTrump camp, which means they’ll now likely cast a strategic vote for Rubio. And despite the attacks Rubio and Bush exchanged during the 2016 primary, the two were former political allies and both members of the Republican establishment in a year when establishment-aligned voters have been dismayed by the rise of Trump and Ted Cruz.

John “Mac” Stipanovich, a Tallahassee lobbyist and longtime Bush supporter, is evidence of Vancore’s theory. Stipanovich is rooting for Rubio, and if Trump becomes the nominee he plans write in his aunt’s name on his November ballot. But he won’t be voting for Rubio on March 15. “I already voted for Jeb when he was still in the race, absentee,” he says. He put his ballot in the mail on February 12.

“People are concerned that votes cast for Bush prior to his suspending his campaign could affect the outcome, probably none more than Senator Rubio’s team,” Florida Republican pollster Alex Patton says in an email. “It appears the race is tightening as we move into the next week, and if it ends up Senator Rubio loses Florida by less than a point then I am sure people will assign blame whether deserved or not.”

On Monday, a Monmouth University poll showed Trump’s lead over Rubio reduced to 8 points, as well as evidence that Rubio was performing very well among early voters, although new polls out Wednesday suggest Trump’s lead may be growing again. As Patton puts it, “in a state with a record of very close elections, everything matters.”