A man in Sparks, Okla., works to clean up damage from an earthquake in 2011.AP

Oklahomans have always had to deal with tornadoes, wildfires, and ice storms. But now residents of the Sooner State are facing a new threat: damaging earthquakes.

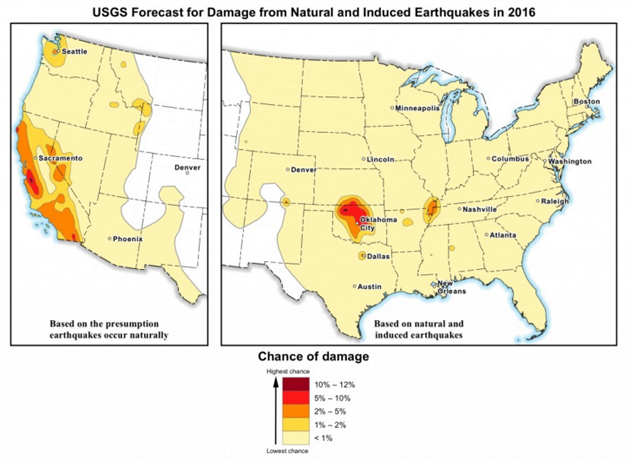

For the first time, the US Geological Survey has included “human-induced” earthquakes in its seismic hazard forecast. These man-made tremors are most often attributed to the injection wells in which oil and gas companies dispose of wastewater from hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking.” The USGS seismologists estimate that some 7 million people in the central and eastern United States now live in areas at risk of a damaging earthquake.

“By including human-induced events, our assessment of earthquake hazards has significantly increased in parts of the US,” said Mark Petersen, who leads the agency’s National Seismic Hazard Mapping Project, in a statement.

The risk is most acute in parts of central Oklahoma and southern Kansas, the epicenter of a fracking boom. According to the new report, the chances of a damaging earthquake (defined as level 6 or greater on the Modified Mercalli Intensity scale) in these areas now range from 5 percent to 12 percent in the next year. Level 6 is considered the threshold at which earthquakes become more than a matter of a few smashed dishes and jolted nerves, causing structural damage in the form of cracked walls and chipped plaster.

However, the researchers say damaging tremors linked to injection wells are unlikely to pack the punch of the strongest earthquakes on the West Coast. The largest earthquake ever in Oklahoma was a magnitude 5.6 on the Richter scale in 2011 centered near the town of Prague, about 40 miles east of Oklahoma City. (A level six MMI corresponds to roughly 5.0 on the Richter scale.) Located near several active injection wells, the trembler injured two people and destroyed more than a dozen homes.

Other hubs of human-induced seismicity identified in the USGS report include the Dallas area, which has seen more than 180 earthquakes since 2008; central Arkansas; and the Raton Basin along the New Mexico-Colorado border. An additional area of natural earthquake activity visible on the map lies along the New Madrid fault west of Nashville.

Typically, the USGS releases hazard forecasts with a 50-year outlook. They are used as guidance for local building codes and engineering design strategies in quake-prone areas. But the new report looks just one year ahead, a decision the researchers say is due to the highly variable risk of human-induced earthquakes from year to year.

In the past six years, that danger has spiked. From 1973 to 2008, the central United States saw an average of 24 earthquakes each year with a magnitude of 3.0 or greater (earthquakes weaker than that are not typically felt). The rate increased steadily between 2009 and 2015, averaging 318 earthquakes per year and reaching 1,010 in 2015. The tremors haven’t abated this year, the USGS says; through mid-March, there have been 226 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or larger in the central United States.

Still, it’s possible the earthquake risk could diminish with similar speed, the researchers note, given that unlike tectonic plates, industrial practices can be regulated. In an interview with the Oklahoman, Tom Robins, the state’s deputy energy secretary, noted that recent efforts to rein in wastewater injection are not yet reflected in the USGS data. That includes a call from regulators earlier this month for a 40 percent reduction in wastewater injection volume.