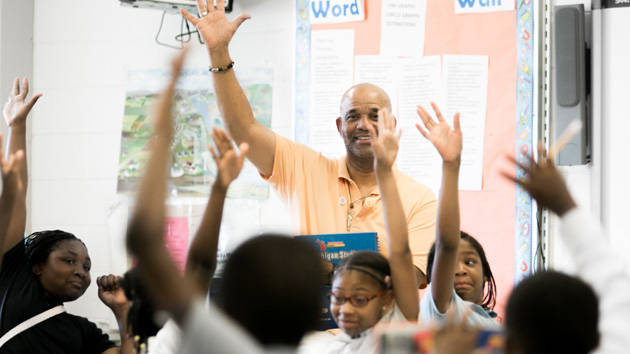

William Weir, an English and social studies teacher, with his students at the Schulze Academy for Technology and the Arts in DetroitImage courtesy of the Bridge Magazine/Brian Widdis

Update 2/2/16: Detroit Public Schools Emergency Manager Darnell Earley announced today that he will resign from his position on February 26, according to WDIV Detroit.

“When I was appointed to this position, Gov. Snyder and I agreed that our goal was for me to be the last emergency manager appointed to DPS,” Earley said in a statement. “I have completed the comprehensive restructuring, necessary to downsizing the central office, and the development of a network structure that empowers the educational leadership of our schools to direct more resources toward classroom instruction.”

“Emergency Manager Darnell Earley has abdicated his role and responsibilities as overseer of the Detroit Public Schools,” said Ivy Bailey, interim president of the Detroit Federation of Teachers in a statement. “As emergency manager, Earley has shown a willful and deliberate indifference to our schools’ increasingly unsafe and unhealthy conditions, and a blatant disrespect for the teachers, school employees, parents and students of our city. Appointing another emergency manager won’t fix Detroit’s education crisis. Now is the time for DPS to have an elected school board that answers to the people of this great city.”

After six years of growing class sizes, pay cuts, the declining quality of student work, and more and more mold, roaches, and rodents in their classrooms, Detroit teachers have had enough. On Thursday, the Detroit Federation of Teachers and several parents filed a lawsuit against the city’s school district, claiming the poor school conditions threaten students’ health and asking a judge to fire Darnell Earley, a state-appointed “emergency manager” who previously worked as an emergency manager for the city of Flint.

A few weeks earlier, teachers staged some of the biggest “sick out” strikes in recent memory. Because it’s against the law for teachers to organize a strike in Michigan, the Detroit educators used their sick days to make their point. During the most recent strike on January 21, 88 of the city’s 104 schools were shut down.

For more than a decade, the system has been struggling with large deficits caused in part by post-industrial middle-class flight from cities and the subsequent decline in school revenues. In 2009, there were about 95,000 students in Detroit’s public schools; last year that number was 48,900. Even though the funding per student has gone up—from $12,935 nine years ago to $17,995 last year, according to Mother Jones calculations—the overall money for the school district is in decline because funding follows the students.

Despite years of cuts and increased class sizes, the “total net deficit” (a budget line that measures shortfalls against assets) has grown from $369 million in 2008 to $763 million in 2014.

Earley is the fourth emergency manager to oversee the Detroit Public School system in almost six years. After Gov. Rick Snyder took office in 2011, he greatly expanded the power of emergency managers. They can now end contracts (including collective bargaining agreements), sell off public assets, abolish or create new ordinances, and decide what authority elected officials—from mayors to city council schools board members—can have over schools. And an emergency manager can make these moves without having to worry about being voted out of office. As Paul Abowd reported for Mother Jones, Michigan’s emergency-manager law is considered by many to be more far-reaching than any other like it in the nation.

A few weeks before the strike, Earley sent a memorandum to all teachers instructing them to report all instances of employees advocating for “work stoppage.”

Under the rule of emergency management. #supportDPSteachers pic.twitter.com/NxIVgiI0Z4

— Detroitteach (@teachDetroit) January 25, 2016

“Teachers call it the ‘snitch memo,'” Margaret Weertz, the editor of the Detroit Teacher, a magazine published by the Detroit Federation of Teachers, told Mother Jones. Despite the memo and a restraining-order request by the district against 23 teachers who took part in the strikes, the protests prompted an inspection of school buildings by Mayor Mike Duggan and a written promise from Earley to take care of the many code violations the inspection uncovered. (Earley’s former work in Flint isn’t helping teachers have faith in their boss and his promises, Weertz added.)

Earley also reportedly failed to meet with teachers in any public forums before the sick outs, says William Weir, a veteran social studies teacher with 19 years of experience in the Detroit Public School system under his belt. Weir tells Mother Jones that none of the four emergency managers he’s worked under “made any real efforts to engage with us.” He added, “The biggest changes and cuts in my school took place under Earley.”

Earley’s office didn’t return repeated phone calls from Mother Jones.

Weir was hired by the Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in 2010 when the school’s scores were at rock bottom. Like much of the Detroit population, 82 percent of the students at Schulze are poor; only 12 percent of the kids’ parents in the neighborhood have at least a bachelor’s degree, according to Bridge Magazine, a nonprofit publication of the Center for Michigan. And yet, even though half of Weir’s students read below grade level and a third of the class has issues that range from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to learning disabilities, a few years ago his students won a statewide award for a research project on the lack of neighborhood grocery stores.

Over the last three years, the Schulze Academy has lost its music, arts, and gym classes, and Weir’s classes grew from 25 students to between 30 and 36 students. Most teachers’ aides are gone, too. And this year, even though Weir is a social studies teacher, the principal asked him to teach English classes. The gym teacher became the social studies teacher.

Because of the school system situation—pay cuts, deteriorating conditions, class sizes—it’s simply difficult for Detroit to attract enough teachers. According to the union, there are 170 vacancies right now. “The English and math tests are the big tests that matter. It was either me or our gym teacher doing English,” Weir explained.

Citing the growing budget deficit, Weir says, “Why should we keep these emergency managers around if they are not doing their main job and the quality of student work is going down?”

Weir believes that Earley and previous emergency managers have added to the deficit by wasting resources on expensive consultants that haven’t increased students’ achievement. “Once we got these managers, we started getting these consultants,” Weir said. Barbara Byrd-Bennett was hired by Earely’s predecessor, Robert Bobb. The Detroit Metro Times reported that Bennett was paid close to $18,000 a month and brought at least six other consultants with her who were collectively paid about $700,000 for nine months of work.

“It’s not that our teachers don’t like professional development,” Weir explained. “But we have all of these successful, experienced teachers right here. Why not pay them to do coaching? They won’t leave like these consultants and they know our kids.”

In the same time, Detroit public school test scores in math and reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the nation’s report card, have remained the worst among large cities since 2009, according to Bridge Magazine.

“These consultants bring expensive books that the principal tells us to take home. And every year there is a new method. And they show you these videos with kids in a middle-class school, with 12 kids in the classroom, and tell us we should teach the same way,” Weir says, “Well, I have 35 kids and about half of them are about three grades behind.”

The consultant-led curriculum, Weir says, “is designed at the grade level and slightly above. Can you imagine being a child who is three grade levels behind? Knowing you’ll be a failure every day you come in?”

“It used to be you’d have a class where five or six kids were behind,” Weir says about the years before the schools started losing students to suburbs and charter schools. “Now you have five or six who are not behind,” he told Bridge Magazine.

About 100 new charter schools have been opened in the Detroit area since mid-’90s taking some of the most motivated and skilled students away from public schools.

Despite all this, Weir—who worked as a police officer before—says teaching is the best job he’s ever had. He wants to be able to meet the kids where they are, he says, providing as much individual tutoring as possible, a difficult task in a classroom with 35 kids and no teacher aides.

Earlier this year, in his first class as an English teacher, he taught the kids a course called “Take a Stand.” Students read standard texts about Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Cesar Chavez, and after weeks of reading and writing, Weir assigned them a research project he had designed himself.

“What would you like to take a stand on?” he asked 35 wiggly, excited 11- and 12-year-olds. “I really miss our gym and music classes,” one student replied. “Why don’t we have them anymore?” another student chimed in.

In the next few weeks, Weir’s students read studies about the cognitive, physical and emotional benefits of music and gym classes. They also researched articles about their school’s financial woes, budget cuts, and emergency managers—and they held a protest in front of their school and wrote letters to their federal, state, and local officials. The state superintendent of Michigan schools, Brian Whiston, responded to students by promising to restore the programs as soon as he can. Emergency Manager Darnell Earley still hasn’t replied.