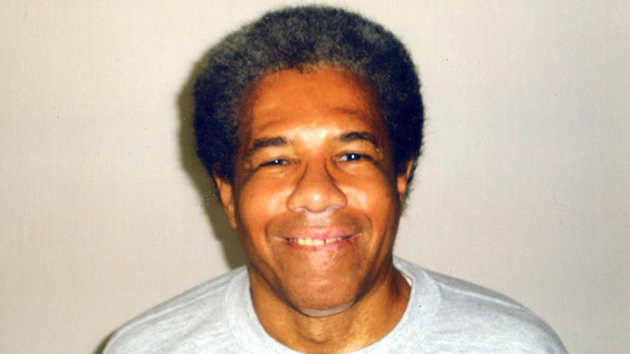

Max Becherer/AP

Albert Woodfox, a cause célèbre in prison reform circles, was freed Friday, on his 69th birthday, from Louisiana custody after a negotiated settlement to end the oldest criminal prosecution in America. He spent nearly 44 years in solitary confinement, mainly at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, commonly called “Angola.”

As far as I know, he holds the record for having been subjected to this punishment for longer than any other prisoner in American penal history. His nearest rival was Herman Wallace, who along with Woodfox was placed in solitary following the 1972 death of Angola guard Brent Miller. Wallace, wracked with cancer, was ordered freed two years ago by a federal court. Outside the prison gates, Carine Williams, one of his lawyers, asked: “Herman, do you know where you are?” The emaciated man looked at her and said, “Yes—I’m free.” He died two days later.

Although the two men were convicted of the murder, they always proclaimed their innocence of the crime that no forensic or physical evidence linked them to. They believed that their Black Panther activism to shield young inmates from the sexual violence that was rampant in Angola at that time was the source of their persecution. Last week, while still maintaining his innocence, Woodfox appeared in Louisiana’s 20th Judicial District Court in St. Francisville to plead “no contest” to lesser charges. “Although I was looking forward to proving my innocence at a new trial, concerns about my health and my age have caused me to resolve this case now and obtain my release,” Woodfox explained in a press release. His attorneys say he’ll now be able to get the medical attention he desperately needs.

The extreme length of solitary confinement endured by Woodfox, Wallace, and fellow prisoner Robert King, popularly known as “The Angola 3,” drew international condemnation. They filed a civil lawsuit in 2000 challenging Louisiana’s use of solitary confinement as cruel and unusual punishment. That fight continues in federal court. “Albert survived the extreme and cruel punishment of 40 plus years in solitary confinement only because of his extraordinary strength and character,” stated George Kendall, the lawyer with white-shoe law firm Squire Patton Boggs who is heading up that fight. “These inhumane practices must stop.”

I know about these “inhumane practices,” because I’ve been there. I spent 44 years in the Louisiana prison system, most of them at Angola, where I served as the editor of America’s only uncensored prison magazine, The Angolite. Twelve of my years at Angola were spent in a cell the size of a typical hotel elevator, stripped of everything but bare essentials, my existence reduced to that of a head of cabbage on a garden row—planted in one spot on earth, forced to spend every day exactly like the last, and the next.

And having spent 12 years like that, I’ll tell you: Life in the vacuum of a cell is spirit-killing, mind-altering, and the zenith in human cruelty. That Woodfox and others like him have survived their experience mentally and emotionally intact is nothing short of miraculous because an isolation cell is designed to break you.

I don’t know what the size of Woodfox’s cells were, but I spent most of my cell years in a 6′ x 8′ space. We were allowed out of our cells into the hallway—one at a time—for only 15 minutes, twice a week, for a shower. There was no rec time, no nothing. We spent years like this, always indoors, with no sunshine. On the patch of floor beside our bunk, there was room enough only for push-ups, sit-ups, and squats, but none of this was sufficient to exercise all of the body’s muscles. Restlessness was bone-deep—a physical ache.

But worse than the physical toll was the toll on our minds, as we wrestled, in isolation, with an empty and senseless existence. Man is a social creature and was never meant to live alone. Yet thousands of prisoners throughout America are, right now, buried alive in steel and concrete tombs, where the only human contact comes when a hand shoves a food tray through a slot in the steel door, or a guard passes by, or a prisoner is taken out to exercise.

We don’t think much about the trivial social interactions that fill our everyday lives—the grocery clerk who wishes us a good day, an elevator passenger who nods good morning, coworkers with whom we exchange small talk, the waitress who greets us with a smile. But these seemingly trivial social relations are part of the glue that holds us together, that lets us know that we have a place in the world. Our interactions with others give us significant feedback about who and what we are—and as we internalize this feedback, it shapes, in large part, how we see ourselves, the possibilities we see for ourselves, and the expectations we set for ourselves. Cut off from normal social interactions, the human mind will make up its own reality. Men become unmoored.

Deprived of the frame of reference that social interaction provides, you lose the sense of yourself as part of a larger whole, the context in which your existence has meaning. You struggle to keep your sanity because in the vacuum of that cell, where there is no meaning, your mind tries to create meaning out of nothing, and this can lead you to confuse fantasy with reality. Besides fighting to stay sane, every day you must justify your existence to yourself, justify why you continue to live like this–which is no life at all–when the rest of the world cares nothing about you and your misery. And it’s worth noting that the vast majority of prison suicides occur in solitary cells, not among the general population—such is the power of isolation. “I’ve seen people go crazy, cutting themselves, hanging themselves. I’ve seen horrors,” Woodfox has said.

The irony of solitary confinement is that it was originally envisioned as a kindness, an 1790 invention of the American Quakers, who wanted to curb the horrors of over crowding in Philadelphia’s Walnut Street jail, and who thought that if criminals were given safety, solitude, and a Bible, they would become penitent and reformed. Instead, it drove them mad. In 1842, the novelist Charles Dickens observed in “Philadelphia and Its Solitary Prison” that the “slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain” made solitary confinement a punishment “which no man has a right to inflict upon his fellow-creature.” By 1890, the US Supreme Court declared solitary confinement to be “an infamous punishment” because of the risk it carries for severe psychological damage to the inmate. Then it looked the other way.

Solitary confinement thrives in America today. No longer gussied up as a misguided “kindness,” it is now deliberately used as the worst punishment penal authorities can get away with. The rest of the civilized world frowns upon it. Mark Donatelli, a nationally renowned criminal defense attorney who has since the 1970s represented prisoners suffering the harsh effects of solitary confinement, says that “the abuse of solitary confinement by the United States has been so widespread and longstanding that the European Court of Human Rights has held up extraditions out of concern that prisoners might suffer torture in violation of international human rights standards.” The European Court is not alone in its alarm. In a 15-page report issued on November 28, 2014, the United Nations Committee Against Torture cited the excessive use of solitary confinement in American prisons and jails as a violation of its guidelines, and recommended a set of dramatic reforms.

It has been little more than a decade since the American mainstream media has awakened to the issue of solitary confinement as a cruel punishment. But it was 21 years ago that I, as editor of The Angolite, requested the identities of Louisiana’s 20 longest cell-confined prisoners and assigned one of my writers to investigate and profile them. Woodfox, who at that time was not much known outside of Angola, gave these thoughtful remarks:

I think now and in some instances, cell confinement for certain periods of time is a necessary evil. Just not for years and years. It’s something like a Jekyll and Hyde situation. Maybe I’ve developed all the emotions and attitudes society and the [Department of Corrections] wanted me to develop—anger, bitterness, the thirst to see someone suffer the way I’m suffering, the revenge factor and all that. But on the other hand, I’ve also become what they didn’t want me to become. I’ve become a well-educated, well-disciplined, highly moral man…It’s sad to say that I had to come to prison to find out there were great African-Americans in this country and in this world, and to find role models that probably contribute more now to my moral principles and social values, when I should have had these things available to me in school.

Not everyone emerges from solitary confinement stronger and smarter than when they entered. That Woodfox has is cause to rejoice, but after 44 years in a box, the difficult but exhilarating work of stepping into a kaleidoscope of a whole new world awaits him. As does his life’s mission—to end the most cruel and evil punishment called solitary confinement.