Gene J. Puskar/AP Photo

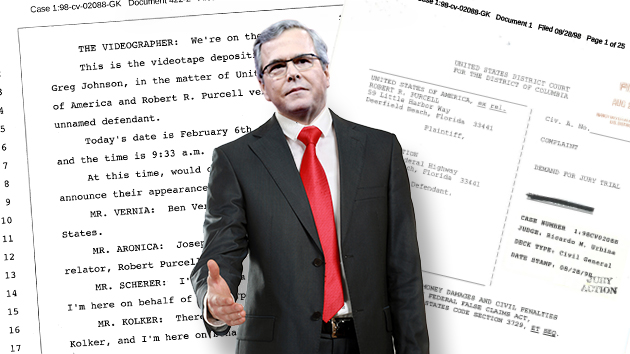

It was 2002, Gov. Jeb Bush was up for reelection, and the Florida Department of Children and Families (DCF) was in chaos. News had recently broken that a five-year-old Miami girl in state care had disappeared—and no one had noticed her absence for more than a year. Police had recently found a child welfare worker passed out drunk in her car with a kid in the back seat. A two-year-old boy was beaten to death on the same day a caseworker claimed to have visited him. The department head had quit amid a series of controversies. Bush needed a replacement, one that signaled that he had a plan to restore order to the scandal-plagued agency. But his choice to fill the job, Jerry Regier, a Christian conservative culture warrior who had served in Bush’s father’s presidential administration, soon landed in a controversy of his own involving spanking.

Regier held a range of hardline religious views and supported the use of corporal punishment against children. He was the founding president of Family Research Council, the social conservative group that has denounced homosexuality and defended the rights of parents to physically discipline their children. (FRC was co-founded by James Dobson, an influential psychologist who, starting in the 1970s, wrote numerous parenting books touting the value of using a switch or belt on defiant children.)

Regier’s hiring offers a window into how Bush governed in Florida. Though Bush is seen as a moderate in the current GOP field of presidential contenders, as Florida’s chief executive he routinely catered to social conservatives on numerous fronts. His administration wasn’t so different from that of his brother George W. Bush, who installed Christian conservatives in positions of power, mingled religion with public policy, and made faith-based governance a centerpiece of his presidency. Bush’s campaign did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

When Bush announced that he had selected Regier for the top DCF post, Democratic critics erupted in protest. They pointed out that Regier was listed as a co-author of a 1989 paper that cited Bible verses—”He who withholds his rod hates his son—as justification for spanking children. It said the Bible gives parents the right to “enforce obedience through discipline, including corporal punishment,” and that such “Biblical spanking may cause temporary and superficial bruises or welts that do not constitute child abuse.”

The paper, titled “The Christian World View of the Family,” was published by the Coalition on Revival, a Reconstructionist evangelical religious organization with the aim of bringing government policy into alignment with its view of the Bible. This outfit also attacked the “radical feminist movement” for convincing men to “relinquish their Biblical authority in the home.”

Regier denied any role in writing the paper, saying that he had just been a member of a committee that issued it. He claimed he had quit the organization after the paper was published when he learned of the group’s extreme views. And he said that he had asked the Coalition on Revival to remove his name from the paper, which the outfit eventually did. (His name is still on the group’s website today, as a member of its original steering committee, the same group that had helped to draft such papers as the one endorsing spanking.)

The other listed co-author of the spanking paper was psychologist George Reker, another founding member of the Family Research Council. Rekers was also a pioneer in the so-called “ex-gay” movement. In the 1970s, he had been engaged in a discredited research project at UCLA that employed spanking to encourage supposedly feminine-acting young boys to go straight. (In 2012, the Miami New Times caught Rekers returning from a European vacation with a young gay escort he’d hired off Rentboy.com.) When critics attack Regier’s appointment to DCF, Rekers insisted that Regier had not had written the spanking paper.

Yet Jay Grimstead, the head of the Coalition on Revival, told the Orlando Sentinel that the controversial paper was one of 17 that the family-life committee, co-chaired by Regier, produced over three years. “Mr. Regier, as far as I know, was one of the editors on this,” Grimstead told the Sentinel.

Reporters unearthed other clips in Regier’s portfolio that suggested extreme religious views, including an article in a defunct magazine that, as the Miami Herald reported, encouraged the use of “manly” discipline of kids. “Most men have been so intimidated by theories on child rearing that they discipline tentatively and often only as a last resort,” Regier wrote, according to the Herald. “The Bible is not at all uncertain about the value of discipline ‘Although you smite him with the rod, he will not die.'” In another article published in a religious magazine called Eternity, Regier endorsed forcing unwed mothers to live with their parents in order to receive welfare benefits and eliminating no-fault divorce.

“It was clear that he had an extremely ultraconservative background,” recalled Nan Rich, who was the Senate Democratic leader in the Florida legislature at the time.

As more and more information was reported about Regier’s views, Bush continued to stick by him. At one point, Bush emailed the then-head of the Family Research Council, Ken Connor, telling him that the press was blowing Regier’s writings out of proportion and targeting him because of his religious beliefs. “I am no longer amazed at the anti-Christian feelings in the press,” Bush wrote.

Regier’s beliefs weren’t so far from Bush’s own. In 1994, as Bush mounted an unsuccessful bid for Florida governor, Bush had supported what critics called the “Spankers Bill of Rights,” legislation that would have shielded parents who spanked their kids from child abuse investigations, so long as the welts and bruises they inflicted were not “significant.” Such measures were strongly backed by Christian conservatives. The Florida legislature passed the bill, but then-Democratic Gov. Lawton Chiles vetoed it. In 1995, Bush published a book called Profiles in Character in which he endorsed paddling students in public school. He suggested that corporal punishment could prevent school shootings.

In an email to Mother Jones, Regier says that in his early life spanking “was a culturally accepted practice,” but he now says he recognizes that “public opinion has evolved considerably in the past 3-4 decades.” He said he never promoted spanking while at the DCF, Family Research Council, or elsewhere. He reiterated that he did not write the Coalition on Revival article that endorsed spanking.

Before Jeb Bush tapped Regier for the DCF job, Regier had served in the cabinet of Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating (R) as health and human services secretary. As a member of the faith-based movement to bring religion into the government, in this post he helped the state divert millions of dollars in federal funding for the poor into marriage promotion programs, many of which were faith-based. (After the state spent more than $70 million to fight divorce and encourage marriage, its divorce rate went up.) Oklahoma state senator Gene Stipe (D) told the Miami Herald in 2002 that Regier was “good at fighting problems that don’t exist.”

In Florida, Regier brought his faith-based approach to the child welfare agency. At one point, according to Florida news reports, he tried to implement a “character-building” program for agency employees that had ties to a fundamentalist minister. In 2003, he enlisted a private company to create an “Adopt-a-Worker” program in which religious congregations would be assigned a child welfare employee to pray for. He encouraged social workers to counsel people accused of child abuse to get married.

In his email to Mother Jones, Regier says that his religious beliefs also led him to involve churches in recruiting foster families and adoptive parents, “an approach in the mainstream of child welfare practice,” and he promoted the religious ideas of “loving and helping ones neighbor, taking care of the widows and orphans and serving the less fortunate.”

Under Regier, and with support from Bush, DCF lawyers once asked a judge to appoint a guardian for the fetus of a severely developmentally disabled girl who had been raped while a ward of the state. (The agency was turned down.) And Regier hired an anti-gay activist, whom he had met at a Family Research Council meeting, as an agency lawyer.

But it wasn’t Regier’s religious views that led to his downfall in Florida. It was a contracting scandal. While heading DCF, Regier was charged with overseeing the privatization of the foster care program and other parts of the safety net. No other state had gone quite so far in its rush to privatize government services as Florida, and Jeb Bush believed that the private sector was the key to fixing the state’s broken child welfare system. Millions of contracting dollars were in play as a result.

Bush’s privatization initiative turned into a feeding frenzy for lobbyists and companies looking to cash in. A blistering July 2004 report by the state’s chief inspector general alleged that DCF had engaged in cronyism by doling out no-bid contracts and that Regier and members of his staff had improperly received perks from lobbyists and others with business before the agency.

Regier resigned a month after the IG report was issued, and Bush continued to support him until the very end. Regier told Mother Jones that while at DCF, he made significant progress in reforming Florida’s troubled child welfare system. Under his leadership, the number of adoptions went up and the backlog of abuse investigations dropped. He said the IG’s investigation had been politically motivated and “fueled a media frenzy that derailed careers, smeared reputations and caused resignations.” He says much of the media coverage was erroneous and points to a subsequent Florida Department of Law Enforcement investigation that cleared him of breaking any laws. He notes that the Florida Ethics Commission also took no action against him.

That Department of Law Enforcement investigation did note “the relationships between DCF management and their vendors may have given the perception of impropriety.” It concluded that Regier did not personally benefit financially from any of the policy decisions he made related to his agency’s contracts.

After the contracting scandal, Regier landed on his feet. He even got a promotion, thanks to another member of the Bush clan. In 2005, President George W. Bush appointed him as a deputy assistant secretary in the US Department of Human Services.