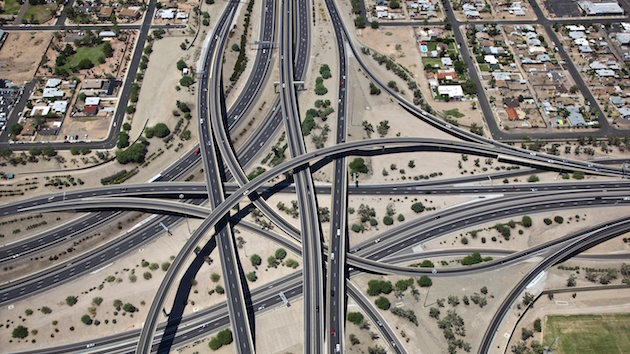

An aerial view of Phoenix, Arizona<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-82854472/stock-photo-aerial-view-of-the-mini-stack-in-phoenix-arizona.html?src=lxy8cJkJd_vP2tn-O3nLyw-1-31">Tim Roberts Photography</a>/Shutterstock

Last week, 19 Democratic governors wrote to Congress, begging House and Senate leaders to address an issue concerning “no less than the economic wellbeing of our nation and the safety of our citizens.” Their dramatic language referred to federal funding for transportation infrastructure projects. Roads, bridges, ports, and transit systems have endured “decades of under-investment and neglect,” the governors wrote, and they want Congress to finally pass long-term legislation to change course.

Federal spending on transportation infrastructure is primarily administered through the Highway Trust Fund (HTF), a fund established in 1956 that receives most of its revenue from federal sales taxes on gasoline and diesel. But to keep dispensing new grants and loans to the states through the fund, the Department of Transportation needs authorization from Congress—and it’s had a hard time getting it.

Authorization for new spending from the HTF expires on Thursday. Two days before the deadline, the House of Representatives passed a temporary measure on Tuesday to keep federal money flowing into the HTF until November 20. The measured was approved by the Senate on Wednesday and is now awaiting President Obama’s signature.

But this means yet another battle over federal spending on transportation projects is still to come. The situation is no anomaly; the three-week patch comes on the heels of a three-month bill and is the 36th short-term funding measure Congress has passed since 2009.

“States need long-term certainty in order to make these key investments in significant transportation projects,” the governors wrote. “Short-run, patchwork solutions by Congress will not do.”

Why is a long-term federal funding bill so important? Why hasn’t Congress passed one yet? And when the governors talk about high stakes, what exactly do they mean? Here are the answers.

Why are the governors upset? The last time Congress passed a transportation bill that guaranteed funding for more than two years was in 2005. Since then, legislators have passed short-term measures that have barely kept the HTF afloat. At the same time, federal funding to the states has held steady at 2005 levels, about $50 billion per year, even as the wear and tear on roads and highways rises.

For the states, this series of short-term fixes means that a key source of funding for transportation infrastructure has become limited and unreliable, causing delays in major state projects. Just last week, the Georgia Department of Transportation announced that it would put off bids for 34 projects worth a combined $123 million “due to federal funding uncertainty.” Tennessee, Arkansas, Wyoming, and North Dakota have also postponed projects. The total value of state highway projects that have been delayed this year now stands at about $2 billion, according to the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

Without federal funds, states are increasingly devising their own financing scheme. Several are raising state gas taxes or vehicle sales taxes; others are hiking assorted registration fees or expanding local governments’ ability to raise funds for infrastructure through taxes and fees. All told, 21 states have approved plans to increase their transportation revenues since 2012, according to data compiled by Transportation for America, a transport advocacy group.

Why is that a problem? There is nothing inherently wrong with states increasing their investment in infrastructure, according to Emil Frankel, a surface transportation expert who served as assistant secretary for transportation policy at the department of transportation from 2002 to 2005. But the federal government has an important role in making sure that adequate investment in transportation reaches poorer and less populated areas. “Typically there is a redistributive effect with the federal programs, taking from states with more resources and giving them to states that don’t have those resources,” Frankel says. “That’s one of the reasons the federal government should stay in the business.”

Also, state efforts are only partly filling the funding gap. A report issued by AASHTO this year found that highways and bridges alone are facing an investment backlog of $740 billion, which will only continue to climb as funding lags.

Why doesn’t Congress act? For years, Congress has not been able to settle on a source of long-term funding for America’s roads, bridges, and mass transit systems, despite widespread agreement that the infrastructure system needs more resources. The HTF is expected to spend $52 billion on highways and transit programs this year while earning just $39 billion. Recently, this gap has been filled by regular infusions from the General Fund, where all federal taxes are pooled, but these bailouts are not a long-term solution: Every infusion requires legislation from Congress, prompting new legislative skirmishes.

Why not raise the gas tax? Transportation advocates have repeatedly called on Congress to raise the federal gasoline tax, which could wean the fund off its dependence on periodic bailouts from the General Fund. The gas tax has remained at 18.4 cents a gallon since 1993, but its purchasing power has been eroded by inflation while more fuel-efficient vehicles have cut spending on gas per mile traveled. Raising the gas tax is popular among economists as well. Harvard professor and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers wrote this month that a gas tax hike of 40 cents would ultimately pay for itself, as drivers would earn back what they spend on the tax through reduced car repair and operating costs.

But politicians on both sides of the aisle are reluctant to back a move so unpopular with constituents, and Republican leaders in the House and Senate have insisted that a gas tax hike is politically unfeasible, leaving lawmakers scrambling to come up with alternate sources of funding. The Senate in July passed a six-year transportation bill that would draw funding from such unusual sources as the sale of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the government’s emergency oil supply. The House rejected the proposal and is now considering a bill that would spend $325 billion on transportation projects over six years but does not say where the money will come from. Neither bill offers a long-term plan: The current Senate bill contains only three years of funding, while the bill in the House would require Congress to pass new legislation after three years to continue spending.

How much money are we talking about? “The absolute minimum level of investment America’s transportation needs—just to keep our traffic from getting worse and our bridges and transit systems from breaking down—is $400 billion over 6 years,” Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx wrote in a blog post in September. To improve and expand the system would cost significantly more. A report published by the Council of Foreign Relations in 2012 found that proper maintenance of highways and the transit system would require up to a 60 percent increase in federal investment, while expanding the system to accommodate the nation’s growing needs would require at least doubling it. But neither the House nor the Senate bills come close to that figure.

What does this mean in terms of our safety? Are our bridges falling down? Not yet, but that doesn’t mean that stagnant funding hasn’t had an impact. “It’s been more incremental and kind of insidious,” Frankel says. “There are safety issues, derailments, congestion grows. It’s a slow, steady deterioration of service and of the quality and condition of facilities. But people don’t notice much until they eventually fail.” A 2013 report by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) found that 32 percent of America’s major roads were in “poor or mediocre condition” and 42 percent of its urban highways were congested.

What’s more, just because the problems are taken for granted, that doesn’t mean that the cost isn’t high. The wear and tear of deteriorating roads costs drivers $109 billion a year, or about $516 per motorist, according to transportation research group TRIP. ASCE has estimated that, if current trends continue, the cost the average user bears for inadequate and deteriorating infrastructure will rise from $130 per year in 2010 to $912 by 2020 and $2,972 by 2040.

Who does this deadlock affect? Everyone, but especially the poor and middle class. The bottom 90 percent of Americans by income spend $1 in every $7 they earn on transportation—nearly twice as much as those in the top 10 percent, the White House said in a report last year.

It is perhaps not surprising that there is broad general support for increasing federal investment. A poll conducted last year for the American Public Transportation Association, a transit advocacy group, found that nearly 68 percent of respondents supported increasing federal investment in mass transit; another poll by the Wall Street Journal and NBC News last November found that more than 70 percent of Americans want Congress to increase spending on road and highway projects.

Have the presidential candidates weighed in? Transportation has been low on the list of priorities so far this election cycle. The topic was barely touched in the first Democratic debate earlier this month, and not at all in the two prior Republican debates, but some candidates have offered proposals. Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton is calling for the establishment of a national infrastructure bank to help fund projects, while Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont earlier this year introduced a bill to spend $1 trillion on transportation infrastructure over five years.

“A $1 trillion investment in infrastructure could support 13 million decent-paying jobs and make our country more efficient, productive, and safer,” Sanders said, adding that this investment would be less than the amount spent on the Iraq War. He did not, however, say where the money should come from.

Few Republicans have raised the topic, with the exception of Donald Trump. Trump said in an interview with the Guardian earlier this month that he disagrees with his opponents’ antipathy toward federal spending on railroads. “We have to spend money on mass transit,” Trump said. “We have to fix our airports, fix our roads also in addition to mass transit, but we have to spend a lot of money…China and these other countries, they have super-speed trains. We have nothing. This country has nothing.”

What happens if Congress does nothing? If Congress fails to authorize new funding in November, the HTF will remain above zero until June 2016—but its decline could force the DOT to slow states’ reimbursements, Foxx said in September. Such a failure appears unlikely: After passing 36 short-term funding bills in six years, lawmakers would most likely be able to pass one more. The more important question is whether Congress will be able to extract itself from the now-familiar rhythm of short-term patches and stagnant funding. The urgency of doing so only grows with each passing year. According to TRIP, vehicle travel rose 39 percent between 1990 and 2013, while the mileage of the roads bearing that surging traffic grew by only 4 percent. In other words, the longer we wait, the harder it will be to fix it.