<a href="https://www.facebook.com/RockTheKasbahMovie/photos/pb.617640091676927.-2207520000.1445283656./859402727500661/?type=3&theater">Rock the Kasbah</a>/Facebook

When noted film director Barry Levinson (Diner, Rain Man, The Natural, Bugsy, Wag the Dog, and many more) first read the script for his new film, Rock the Kasbah, he realized he needed the help of a pop icon: Yusuf Islam—that is, the singer/songwriter formely known as Cat Stevens.

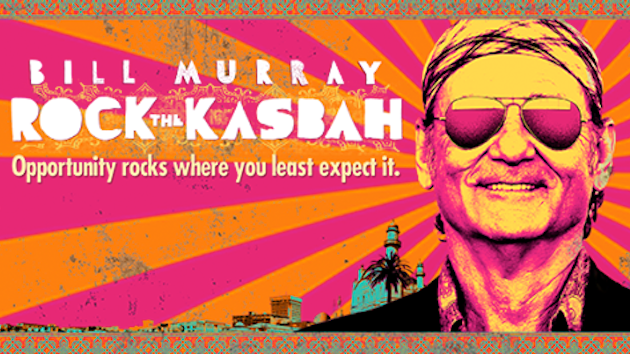

In this comedy (dark at times, sweet at times), which opens this weekend, Bill Murray plays a down-and-way-out LA talent manager who has but one act left in his falling-apart stable, a neurotic bar singer (Zooey Deschanel). Yet somehow he finds a gig for her: USO shows in Afghanistan. And off they jet to the war zone, where soon Murray’s only meal ticket abandons him, and he’s stranded in Kabul with no passport, no money, and no way home. Hijinks—and violence—ensue, as Murray falls into the world of sleazy arms dealers, cynical American mercenaries (including a tough guy played by Bruce Willis), and competing tribal warlords. But this is no adventure flick. It’s a tale of cultural and spiritual bridge-building—with laughs—because Murray, stuck at one point in rural Afghanistan, stumbles into a cave and discovers an Afghan teenage girl (Leem Lubany) singing beautifully. And the song she’s covertly crooning is Cat Stevens’ “Trouble.”

From here on, Murray has a mission: to get this Muslim teen on the Afghan version of American Idol, which has never featured a female performer. The film is based, as they say, on a true story, and the real-life Afghan woman who appeared on this television show, Setara Hussainzada, confronted tremendous opposition from religious and cultural conservatives; she even received death threats and fled Afghanistan for exile in Germany.

Levinson’s film tracks a tale of female empowerment in the Muslim world, while—get this!—being respectful of the society it portrays. Most of the laughs it generates are at the expense of Murray’s character, not cheap gags aimed at the natives. As Levinson put it, he was looking to craft “a humanistic, dramatic comedy that dealt with the Muslim world in Afghanistan.”

The script, penned by Mitch Glazer (Scrooged, Great Expectations) had been knocking about Hollywood for years without being made, even though marquis-name Murray was attached to the project. “It was too foreign some said,” Levinson explains in a blog post. “Too much about that part of the world, not enough action, not a war film, too much about people, and in whispers, too much about Muslims.” (Fahim Fazli, the actor who plays the father of the teenage girl, recently told an interviewer that this was the first time in his 25-year acting career that he wasn’t cast as a terrorist.)

But Levinson, Glazer, and the rest of the film’s team were able to get the movie going on a basement budget (just $15 million)—with the actors pocketing lower-than-usual rates—but they needed the okay of Yusaf Islam. At least, to a certain extent.

Several Cat Stevens songs play a critical role in the movie, so much so that Stevens is something of an unseen co-star. And the film’s climax—slight spoiler alert—makes effective use of his anthemic “Peace Train.” So when Levinson read Glazer’s script and saw that it included these tunes, he asked, “Do we have the rights?” Not yet, he was told.

Usually, it’s not a big deal for a director to obtain the rights to use music in a film. The music supervisor contacts the folks who control the rights to a song and negotiates a deal. But it was not so simple in this case. Yusuf wanted to meet Levinson and Glazer. So on a spring afternoon in New York City, hours before Yusuf was to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Levinson tells Mother Jones, he and Glazer met with the singer at his hotel. There was a bit of apprehension on the filmmakers’ part. If Yusuf said no, they weren’t sure what they would do. “We didn’t know what we could use instead, what would get us there,” Levinson says. The Cat Stevens songs were instrumental to the story. (After all, how many Muslim-Western mega pop stars are there?)

Yusuf had been sent a copy of the script, and shortly after the introductions were done, Levinson and Glazer were relieved: He liked the story and was excited by the prospect of being involved in the project. “He wanted to make sure his music was being used appropriately,” Levinson says. “And he saw exactly what we were trying to do with the whole idea of an Afghan Muslim young woman so taken with his music that she becomes a pop star and remains a Muslim.” Islam gave them a green light. “It was a key element to get into place,” Levinson notes.

“It was our idea to do a film that’s not political or war-related,” Levinson adds. “And he saw it exactly as Mitch Glazer wrote it.” Months later, Levinson, Murray, Willis, Deschanel, and the rest of the cast and crew were filming in Morocco, on a tight 28-day schedule and a slim budget.

Competing with big-budget films, Rock the Kasbah may have a tough time finding its audience. But the Cat Stevens-imbued film is an unconventional attempt to depict this Muslim society in non-Hollywood fashion—while prompting plenty of laughs. (Murray nails the part of the dodgy former LA player who’s living in a derelict motel and incessantly dropping the names of the big-time rockers he supposedly used to run with.) As Afghan American journalist Fariba Nawa notes, “The filmmakers capture the tragedies of my homeland through comical idiosyncrasies. The movie switches from stereotype to kitsch, and it’s the absurdities that reflect the truth…I appreciated seeing Afghanistan through the humanity and smiles of the film’s Afghan characters.” She thinks the film succeeds, avoids the usual Hollywood traps, and depicts Afghanistan “in all of its complexities.” If that’s the case, a piece of the credit goes to Cat Stevens.