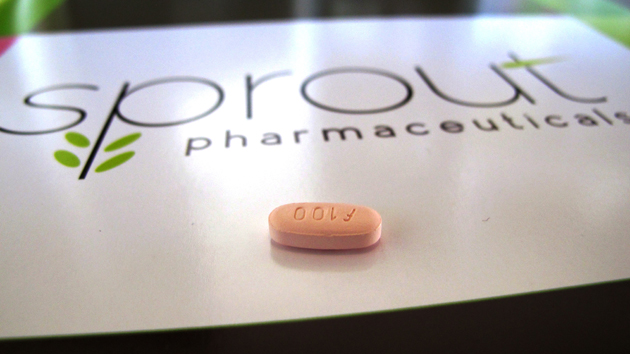

The new libido booster for women goes on sale October 17.Allen G. Breed/AP

The path to market for the first-ever women’s libido drug began in 2010 when Dr. Irwin Goldstein chased a pharmaceutical executive around a Miami medical conference.

“Irwin is famous for chasing people around with his MacBook,” says Cindy Whitehead, the CEO of Sprout Pharmaceuticals and Goldstein’s quarry that day. “And you’re always a little scared of what he’s going to show you on video.”

Goldstein is one of the top researchers in the budding field of sexual medicine. But on this occasion, he showed Whitehead videos of his patients—clothed—as they relinquished samples of a drug they had been receiving through clinical trials. The drug was a female libido booster called flibanserin, and the pharmaceutical giant that owned it was shutting down the clinical trials. The women looked dejected. Several of them cried.

For Whitehead, it was an “aha” moment. The encounter sent Sprout on a quest to obtain the rights to flibanserin and a five-year saga of costly clinical trials, aggressive lobbying, and fraught regulatory meetings that ended last month when the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug for sale under the brand name Addyi.

For others, the moment was another case of Goldstein’s expert leveraging of his ties to the pharmaceutical industry. To these critics, Goldstein’s work raises the same controversy that is dogging flibanserin: Is he advancing the frontiers of medicine, or the bottom line of the pharmaceutical industry?

The criticisms of Goldstein are tied to the combative lobbying campaign for Addyi’s approval and doubts about the drug’s effectiveness. The FDA declined twice to allow flibanserin on the market, in 2010 and 2013, saying the drug’s risks outweighed the payoff. Women on flibanserin experienced only 0.7 more satisfying sexual events a month than women taking a placebo, according to daily questionnaires the women completed. (They did report feeling more sexual desire in monthly surveys.) The side effects include nausea, dizziness, fainting, and severely low blood pressure, and they increase in frequency and severity in combination with alcohol. The risk is great enough that women using flibanserin, which must be taken daily, are advised not to drink at all.

When Sprout put flibanserin before the FDA for a third time, an outside group with connections to Sprout mounted a paid lobbying effort to paint the FDA’s decision-making as sexist because the agency had previously approved many drugs to treat sexual difficulties in men. Some prominent women’s groups found the campaign ludicrous and trivializing of feminism. But this time, Sprout was successful.

Many sex researchers dispute the idea that women’s sexual difficulties can be solved with drugs. They argue that women’s sexual issues are much harder to diagnose than a disorder like erectile dysfunction, which has obvious physical signs. In the case of flibanserin, experts are alarmed by the effort to define low sexual desire as a medical disorder, as there is no consensus on what constitutes normal sexual desire. One prominent drug-marketing researcher called the process “a classic case of disease branding.”

“Most people in the field who are not involved in drug development—researchers and clinicians—would agree that these terms are very fluid and unsatisfying,” Leonore Tiefer, a sex researcher and psychiatrist at the New York University School of Medicine, says of diagnoses like female sexual dysfunction, “and that we still lack a really comprehensive understanding of sexual desire.”

Goldstein, who is now a consultant for Sprout, is the leading voice for the opposite point of view. “There are women whose lives are completely devastated by this condition,” he says. “I see these women every day. Before [Addyi], we had no treatment options for women besides talk therapy.” After the FDA approved the drug, he told the health care industry news site MedCity News, “If you have a broken leg, a broken toe, or a broken libido, you can now go to a doctor and get help.”

Sexual medicine is not on the roster of the American Board of Medical Specialties’ many dozen recognized specialties or subspecialties. Goldstein has spent much of his 30-year-plus career taking pains to ensure that it someday could be. Through Goldstein’s efforts, the field of sexual medicine now includes a handful of medical societies, a well-regarded journal that Goldstein edited for 11 years, and a training program for students and physicians. Goldstein has received grants for decades from the National Institutes of Health, mostly for the study of male sexual dysfunction. “He’s truly been a visionary in moving this forward,” Whitehead says.

But Goldstein’s many ties to the pharmaceutical industry have led Tiefer and others to argue that Goldstein expanded the field of sexual medicine in coordination with drug companies, sometimes right as those companies were developing new treatments for sex disorders. And they see his role in defining female sexual dysfunction as a prime example.

Many of the first meetings Goldstein convened on female sexual dysfunction were dominated by members of the pharmaceutical industry and sex researchers with connections to the industry. His early awareness campaign for the disorder included a presentation at a free conference for medical and science reporters underwritten by three drug companies with sexual dysfunction drugs in the works; a biomedical ethicist at McGill University labeled this “an extreme [case] of entrepreneurialism in clinical trial research.” A research team overseen by Goldstein produced materials for a training program that has introduced female sexual dysfunction to hundreds of doctors throughout the country. Ray Moynihan, a journalist who has written extensively about the role of drug companies in publicizing female sexual dysfunction, reported that the training program is funded by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer. Goldstein has consulted for several of the world’s largest drug companies, and today he receives several thousand dollars a year as a consultant to Pfizer on Viagra.

“He worked very hard to organize doctors, mainly with links to drug companies, to really get behind this diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction,” says Thea Cacchioni, a sociologist at the University of Victoria in Canada who studies the medicalization of women’s health. “It was a very clever move, a kind of pre-organizing of the market. You don’t have a drug yet for women, but let’s make sure there’s a label, a diagnosis that the drug would treat.”

Sue Goldstein, an executive with several leading sexual medicine organizations and Irwin’s wife, called the assertion that the field of sexual medicine emerged with the help of the drug industry a “fabrication.” She notes that many of Irwin’s critics do not have medical science credentials, and that Tiefer ran a political campaign of her own, against the approval of flibanserin.

“Irwin has been treating people with sexual dysfunction for 35 years, long before there were any pharmaceuticals in the field,” she says. “There is no reason we would be interested in helping their bottom line.” As to the Pfizer grant, she notes, “Most educational programs are underwritten by unrestricted educational grants.” She adds that at a meeting in 1999 where 700 physicians and researchers voted to create the first society devoted to sexual medicine, the majority had no ties to drug companies. Goldstein himself, she says, had no ties with any pharmaceutical companies working in female sexual dysfunction at that time.

That large gathering, however, was the product of several smaller, private meetings at which industry ties were apparent. One of these, convened by Goldstein in 1998, resulted in a mini-manifesto that defined female sexual dysfunction and recommended treating it as a medical condition. At the time, Pfizer was running clinical trials to study Viagra in women. A New York Times reporter said the research was prompting a difficult question: “What is the female problem that Viagra or some drug like it would solve?” Eighteen of the 19 authors of the paper defining female sexual dysfunction disclosed ties to drugmakers.

Starting in 1999, Moynihan reported, Goldstein organized three annual conferences on female sexual dysfunction with up to 20 corporate sponsors, including Pfizer. (A doctor working for Pfizer told Moynihan that the company’s role was passive.)

The definition of female sexual dysfunction is still hotly contested. But the disorder has gained acceptance from several major medical groups and, critically, the FDA. “The FDA strives to protect and advance the health of women, and we are committed to supporting the development of safe and effective treatments for female sexual dysfunction,” Janet Woodcock, the agency’s director of drug research, said in the announcement of Addyi’s approval. Stephanie Faubion, the director of the Women’s Health Clinic at the Mayo Clinic and a supporter of the effort to bring the drug to market, has greeted the new drug with cautious approval, saying, “While this drug has several potential side effects, so do many antidepressants that are given to women routinely.”

Goldstein is not cagey about his web of ties to pharmaceutical companies, nor does he see them as harmful. “Serving as a consultant to pharmaceutical companies helps me ensure that the research they’re performing or results they’re interpreting match what we in the field understand about women’s sexual function,” he says. “I’m seeking the best possible treatment options that might be available to my patients.” Government grants for the study of women’s sexual health, he says, have dried up. “Thankfully,” he adds, “the private sector was still interested in having research performed.”

He finds the notion that he formed institutions to pre-organize the market for flibanserin “preposterous,” noting that researchers first identified the specific subset of female sexual dysfunction that the drug is intended to treat 40 years ago. “I just cannot understand—it just makes me a tiny bit crazy—how something that actually helps women’s lives would be so criticized,” Goldstein says. “They have another agenda.” In the past, pharmaceutical executives have said explicitly what they think is driving that agenda: the fear that drugmakers will find a pharmacological solution to a sexual disorder that is currently monopolized, treatment-wise, by psychologists.

Goldstein’s profile rose in connection with the 1998 FDA approval of Viagra, Pfizer’s breakthrough erectile dysfunction drug. Goldstein was instrumental in the clinical trials. Once the drug was approved, the company began a media blitz in which Goldstein was a central figure, although Sue Goldstein says he was not paid by Pfizer to do interviews.

Goldstein stood apart for his willingness to promote new uses for Viagra. He told USA Today and the New York Times that he was prescribing Viagra to women. A fellow Pfizer consultant called this practice “irrational,” because there was not much evidence that Viagra caused arousal in women, and there had been no safety studies. (Four years later, a Pfizer-led study concluded that Viagra was useless to women.)

Goldstein also suggested that Viagra could be used to prevent future erectile dysfunction. “People take aspirin to prevent heart attacks,” he told Reuters. “Is Viagra the aspirin of the penis? We think it is.” Several years later, before a large audience of prescribing doctors, Goldstein said he had given hundreds of men Viagra as a preventative measure. Goldstein said the practice was backed by good evidence—in contrast to Pfizer, which said there was no evidence one way or the other.

As flibanserin began to look promising, Goldstein rallied the institutions he helped launch to spread awareness about the specific disorder the drug was designed to treat: hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), a subset of female sexual dysfunction. Before Sprout obtained the rights to flibanserin, the drug was under development by the German pharmaceutical giant Boehringer Ingelheim. The company relied on Goldstein as an investigator in some of its clinical trials. At the same time, Goldstein took to the pages of his journal, the Journal of Sexual Medicine, to urge doctors to begin discussing HSDD with women in more patient-friendly terms.

Then, in 2010, the FDA denied approval for flibanserin. Boehringer Ingelheim decided to shelve the drug, with no apparent plans to sell the rights. That’s when Goldstein grabbed his camera.

The move was pure Goldstein, according to Tiefer. “His skills and his energy are legendary,” she says. “He’s every place. I can picture him with a drink in his hand meeting everybody in the room at every meeting that I’ve ever gone to.”

Now a consultant to Sprout, Goldstein continued to provide institutional support for the approval fight. In October 2014, as the FDA prepared to consider flibanserin, the agency selected female sexual dysfunction as the subject of one of its public education hearings. (Previous subjects for these hearings included HIV, lung cancer, and sickle cell disease.) One of the medical societies Goldstein helped establish urged its members to recruit their patients to speak at the hearings. Even the Score, the lobbying effort that made the feminist case for Addyi, used undisclosed donations to help the patients travel to the hearings. Several of the patients who testified were Goldstein’s.

Sue Goldstein says Irwin’s patients were heavily represented because their San Diego clinic is one of very few that focus only on sexual dysfunction, and because his passion on the issue is contagious. She says his campaigning comes from a personal place.

“The bottom line is that I am a woman with HSDD,” she says. In addition to testifying at the 2014 hearings, she interviewed women with the condition for a self-published book and oversaw clinical trials for the drug. “Over and over and over, I saw the destruction, not only to the women themselves, to their relationships, to their hopes. I had women crying in my office when the flibanserin trial ended, because they thought, this is going to be the end of my relationship. And it’s hard for someone who’s never experienced HSDD to appreciate it.”

Irwin Goldstein adds that many of the women at the hearings came at great personal cost, missing a parent’s funeral or a son’s first birthday party.

Tiefer and PharmedOut, a project of the Georgetown University Medical School that opposes overdiagnosis, sent the FDA letters cosigned by hundreds of medical professionals opposing the drug’s approval. PharmedOut called pressure to approve the drug an “unprecedented and unwarranted manufacturer-funded public relations campaign.”

Flibanserin was ultimately approved by an 18-6 vote with the agency’s strongest warning label. Only specially trained physicians may prescribe it.

In the wake of the approval, Goldstein is playing a similar role to the one he played during Pfizer’s Viagra victory lap, expounding on future uses for the drug, which goes on sale October 17. He was cited in the New York Times as saying he would not necessarily refuse the drug to casual drinkers, although Goldstein says his position was oversimplified.

“Everybody makes their own personal decision on risk-benefit,” he says. “Sex is something that is so important to a relationship. It’s where intimacy happens, it’s where bonding happens, and if that’s not part of a relationship, that’s a big issue, especially in a man. Men just give up on this thing. So if a woman came to my office, and she said, I read the package insert, and I’m aware of the risk, and I’m aware of the benefits, in my personal life, I need to do something,” then, he says, he would prescribe the drug.

Sprout, meanwhile, has been acquired by a Canadian drug company, Valeant, for $1 billion. Goldstein is electrified at the possibilities for all that new capital. “We’re dying to get this approved in menopause,” he says. “There are a ton of studies I’d love to do.”

Whitehead agrees. “It’s super exciting to imagine the possibilities of future study,” she says. “Irwin of course would be among others who would continue to research in this category.”

She adds, “Were it not for Irwin Goldstein, I don’t think I would have taken on this drug.”

This story has been updated.