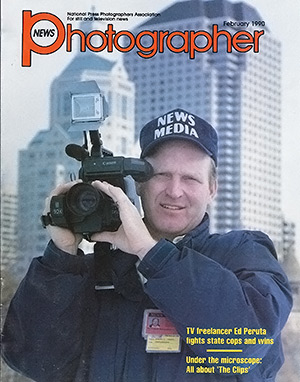

"They can call me a gadfly. They can call me whatever they want to call me." Courtesy of Edward Peruta

“The NRA asked me to keep my mouth shut, but I’ve never run from a fuckin’ interview in my life,” Edward Peruta barks into the phone. The 66-year-old Vietnam vet, ex-cop, public-access TV host, worm farmer, legal investigator, crime scene videographer, and serial litigant has never been one to hold his tongue, and he’s not about to start now that he’s at the center of a high-profile case that could upend California’s gun laws and wind up before the Supreme Court. “I am who I am,” he says. “People know there’s usually a hurricane comin’ if they step on my rights.”

Peruta is the lead plaintiff in Peruta v. County of San Diego, a federal lawsuit that seeks to overturn California’s system of issuing concealed-weapon permits. Currently, the state’s police chiefs and sheriffs may require applicants to show “good cause” for carrying a concealed gun in public. Such discretion is applied arbitrarily and violates the Second Amendment, according to Peruta and his legal team, which is backed by the National Rifle Association.

That argument swayed two judges on the 9th Circuit Court, who ruled in Peruta’s favor in February. For a moment, it seemed that California would join the 37 “shall issue” states that issue concealed-carry permits to anyone who meets basic requirements such as a background check. Then California Attorney General Kamala Harris successfully petitioned the court to reconsider the ruling en banc. Next Tuesday, an 11-judge panel in San Francisco will hear oral arguments in the case.

Both sides of the gun debate are watching Peruta intently. “If the California permitting system were struck down, that could be the difference between tens of thousands of people and a million or more people carrying in public,” predicts Mike McLively, a staff attorney at the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which has filed an amicus brief in support of the current law. Gene Hoffman, chairman of the Calguns Foundation, which is sponsoring a similar case that will be heard alongside Peruta’s, expects the Supreme Court to step in after the 9th rules: “I think they’re gonna take this case whatever direction it goes.” Likewise, the NRA has said Peruta “presents an opportunity for the Supreme Court to settle some Second Amendment issues that desperately need resolving.”

“I’m not a gun advocate,” Peruta says. “I don’t know about all kinds of different guns. But I know how to use one.” What triggered his case is what has set off a lot of his crusades over the years: A public official told him he couldn’t have what he believed he was entitled to by law.

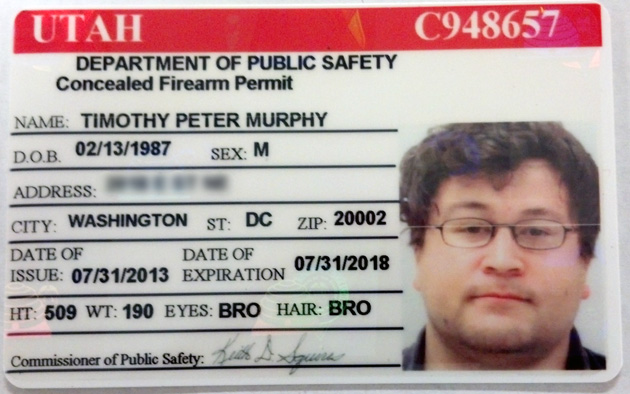

In 2008, Peruta applied for a permit to carry a concealed handgun in San Diego, where he spends part of the year living in his 40-foot Country Coach mobile home. He told the county sheriff’s office that he needed a gun for self-defense in his RV and while working as a legal investigator and spot-news videographer who sells shots of crime scenes and accidents to media outlets. The sheriff’s office denied his application and appeal, finding that he wasn’t a San Diego resident and could not demonstrate any specific threats to his safety. Peruta, who has gun permits in Connecticut, Florida, and Utah, recalls meeting with an administrator in the sheriff’s office: “I asked him where the hell he thought he came from. He asked me what I meant. And I said, ‘Is there a federal court in this town?’ And the rest is history.”

Over the years, Peruta’s refusal to take no for an answer has gained him a reputation in his home state of Connecticut as a bane of bureaucrats and a liberator of public information. But his bluster and hard-charging manner have also earned him some less flattering labels. “What did they call Sam Adams in Boston in 1775?” he snaps. “They can call me a gadfly. They can call me whatever they want to call me.” And his contentious, “colorful” life, which includes a long list of legal scuffles, a brief and turbulent stint as a police officer, and involvement in a securities-fraud case, has led some pro-gun advocates to wonder whether he should be the poster boy for their efforts to ease restrictions on hidden firearms.

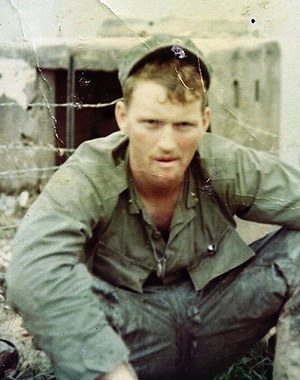

Peruta’s battles began in 1967, when he dropped out of high school and shipped out to Vietnam with the Marine Corps. He fought through the Tet Offensive, got noticed for his impressive marksmanship, and made a vow to keep fighting when he got back stateside. “I have a lot of people that aren’t around anymore,” he says. “They’re still 18, 19, 20 years old, laying in a fuckin’ box in national cemeteries. We all promised each other that we would never, never give up. We would never yield to bad government decisions.”

After coming home to Connecticut, Peruta joined the Wethersfield Police Department in 1969. “I went to the police academy and came out third in my class,” he recalls. “I learned the law. They did teach me how to read the law, how to understand the law, and how to implement the law.” However, he was fired as a patrolman in 1971 before his probationary period was over, and the following year, he unsuccessfully applied to join the force in neighboring Rocky Hill.

Peruta’s thwarted law enforcement career came up again when he moved to Vero Beach, Florida, in the late ’70s. After Peruta complained about the city’s failure to restore his power after a hurricane, the mayor grumbled that he was part of the “2 percent lunatic fringe.” (“I am very proud of that title,” Peruta says.) The mayor also asked the police to secretly look into Peruta’s background, expressing concern that he “might do something erratic at a council meeting with a lot of people present.” According to documents Peruta obtained, the Vero Beach police chief contacted Wethersfield’s then police chief, T. William Knapp, who said Peruta had been “a disorganizing factor on his department.” Knapp also reported that “Peruta wishes to be controversial and take opposite views of others. In plain English, he is an ass, but nothing in his past would indicate that Peruta would engage in any violent action.”

“That’s when I declared war on Vero Beach,” says Peruta, who recalls his righteous grudges against past nemeses in exhaustive detail. (He tells me that the Vero Beach police captain who did the background check was later caught using official equipment to photograph nude women; sure enough, he’s right.) In 1981, Peruta sued Knapp, who happens to be his first cousin, for making “false and malicious” statements about him in the background check; that case, filed in Connecticut, was eventually withdrawn. Peruta also sued Knapp in federal court; that case was dismissed. He also unsuccessfully sued Wethersfield and Rocky Hill for $3 million in damages.

“He sued me two or three times when I was police chief. But I think what’s he’s doing is right,” says Knapp, who served 15 years as Wethersfield’s chief of police before overseeing Connecticut’s police training program. Knapp says Peruta can be intense and abrasive, but stands up for his beliefs: “Eddie Peruta is a champion of the underdog in a variety of cases, not just guns.”

Unemployed and on the hook for for child support, in 1984 Peruta took a job with a Vero Beach firm running what police later termed a “boiler room operation” selling gold- and silver-backed investments. Peruta says he had no idea any laws were being broken. He pleaded no contest to three third-degree felonies with no adjudication of guilt and was sentenced to three years’ probation. Peruta states that he has fully disclosed the case whenever he has applied for firearms permits.

He then returned to Rocky Hill, where he became a fixture of its small-town political scene. “I can’t fart in Connecticut without making the news,” he says. A showdown flared in 1990 after he admitted to the police chief that he had spanked his son. Peruta filed a federal civil rights suit against the chief for initiating child abuse and fraud investigations against him and eventually got a $35,000 settlement. (He says he could have asked for more, but wanted to deprive his lawyer of a bigger contingency fee.) He also took his revenge by forcing the public disclosure of the chief’s 790-page work diary, which was crammed with lurid allegations about local residents and officials. Peruta took another scalp in 1996, after his son was suspended from high school for reportedly smoking pot. Peruta requested the school’s student discipline records; the principal resigned after he was accused of withholding them.

In 1995, Peruta opened a motocross track. When the town and the state tried to shut it down, he responded that the land was in fact a worm farm and that riders were free to collect as many wrigglers as they liked. “As yet, none have exercised their worming rights,” the Hartford Courant observed dryly when the operation was approved after a two-year fight.

Peruta set up a news organization, American News and Information Services, rushing to shoot video of crime scenes and accidents, which he’d sell to media outlets. “I get the flames and the mainstream brick and mortar media gets the ashes,” he boasts. He got tips from cops, but also sparred with them over his right to film in public. He also took to the airwaves as the host of his own public-access cable show. (He still appears on a program called Summary Judgment.) In 1999, he was criticized for putting on a curly black wig during an on-air discussion of the shooting of an unarmed black teen by a white police officer. Peruta publicly apologized while accusing his critics of “racial extortion and intimidation.” In 2000, the local cable provider tried to move Peruta’s 8 p.m. show to a late-night time slot due to his use of profanity; Peruta went to federal court and won.

“He was a gadfly,” recalls Scott Coleman, a computer store owner and fellow activist who clashed with Peruta. “He could be very aggressive and loud. But there is a good side of him; he sticks up for the little guy.” In 1996, the Hartford Courant estimated that Peruta had sued Rocky Hill six times and had lodged 70 freedom of information complaints against the town. Peruta told the newspaper that he was “not a crazy, insane gadfly with no other purpose in life but to harass public officials. There is a reason for what I do.”

Between the time he left the Wethersfield Police Department and the mid-2000s, Peruta says he never owned a gun. “I had no desire,” he says. “I was more involved in watching government and helping people get unjammed.” He first became active in gun rights in 2007, when he became a legal investigator for Rachel Baird, a Connecticut firearms lawyer.

Yet as his focus expanded beyond the First Amendment to the Second, his past followed him. In December 2007, an anonymous user on the OpenCarry.org forum posted a link to a 45-page file called the “Peruta Papers.” It included news articles about Peruta’s various exploits, including the Florida securities case. The file also contained what appeared to be transcripts of documents from his personnel file as a rookie cop in the early ’70s. In a grainy copy of a report filed in 1971, Knapp, then a lieutenant, described responding to a domestic incident that resulted in him temporarily removing Peruta’s service pistol and a snub-nose revolver from his home. In another document, Knapp told the Wethersfield police chief that he did not think that Peruta should be retained as an officer due to his “immaturity” and volatility.

As Peruta’s case against San Diego progressed and started to make headlines, the Peruta Papers popped up again. In January 2010, Hoffman, the chairman of the Calguns Foundation, alluded to the dossier on his group’s busy message board. Hoffman questioned Peruta’s suitability as the public face of an increasingly visible case, citing his apparent “odd separation with law enforcement.” Hoffman continued, “None of it rises to the level that should deny you a right to carry, but it may not make you the best plaintiff to represent gun owners under any intense media scrutiny.” In 2011, Hoffman posted a link to the Peruta Papers, warning, “I think the other side could make some serious hay with these facts.”

Peruta says that while the documents in the Peruta Papers aren’t fake, his “quote unquote personnel file” was part of a “hatchet job” that ended his dream of being a cop. “You can’t believe everything you read—and I was there when the script was written,” he says. He acknowledges that Knapp took his guns and returned them two days later. As for Knapp’s comments about his temperament as a cop, “in 1970, 1971, based on what was going on, that may have been a fair assessment.” He says he lost his job as a patrolman because a vindictive superior wrote him up for failing to shoot an African American man who fled from a traffic stop. More than 40 years later, his anger over the affair hasn’t abated. “It was a fuckin’ lie!”

Knapp, who is close to his cousin despite their past tussles, agrees that the documents don’t tell the whole story of Peruta’s short law enforcement career. Asked if he ever questioned Peruta’s maturity to be an officer, Knapp replies, “I might have said that. I don’t think Eddie would have been a very efficient police officer. He’s very intense and doesn’t particularly care to take orders.” But, he adds, “I never worried about him shooting anybody.”

Peruta declined to provide a copy of his complete personnel file, which he’s had since he sued Knapp for it in 1976. The Wethersfield Police Department says it no longer has it. The Peruta Papers can be traced back to a now-dormant community message board in Rocky Hill, which included a section dedicated to Peruta. Coleman, who ran the site, insists the documents are accurate. He says he received them from “somebody in Wethersfield who didn’t have a love for Peruta.” He claims he can’t recall who it was. While Peruta has never asked that the documents be taken down, he told me, “Anybody who publishes something about me that’s not correct, I have the option to say, ‘Now it’s game time.'”

Hoffman says his concerns about Peruta have eased, though he is relieved that other rejected concealed-carry applicants have joined Peruta v. San Diego. “The NRA has added plaintiffs who are legitimate public interest plaintiffs,” he says, such as a retired doctor who wanted a concealed weapon to protect himself from antiabortion extremists. Despite its financial support for his litigation, the NRA has not profiled Peruta in any of its promotional materials.

Though he’ll go to San Francisco to watch the oral arguments in his case, Peruta says what happens next is out of his hands. The plan after the 9th Circuit Court delivers its ruling is “not my plan, it’s the NRA’s plan.” But he’s busy with new causes, dropping hints about a potential case involving a cop who told him not to film a murder scene and assisting with a defamation lawsuit against Everytown for Gun Safety.

“Do I believe that everybody should have a firearm? Absolutely not. Do I believe that there’s people who should be prohibited? Absolutely.” Yet the way California currently determines who can or can’t carry a gun in public clearly infringes on the Second Amendment, he says. As usual, Peruta is certain that the law is on his side. “You don’t like it?” he booms. “Change the fuckin’ Constitution!”