<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/5844354288/in/photolist-oAQ3p3-h5afPL-oTiEq6-gb3cqB-av6umx-gHYFC3-rAnv1C-f2Veuo-gNF8L3-fmjviZ-9bvh7X-9UrQV7-qacmJh-fyjqEN-ehqPY1-myp9DR-q8eEc8-qTskgB-fmzuvA-ehqQfW-rKw7pS-ehk63T-ppGRvp-fmzrZb-nG7paW-bEXejf-bTRZU2-qBswDA-e4rMFU-av6uxZ-dcmShJ-g6RiAt-e4rLrw-bEWKuN-bEWGgy-fmjJnc-ryoZz5-av6uvr-rsAB6z-fmztg9-e4m9QZ-fmjVmR-e4m9nD-e4rNaC-e4mbDK-9DR8Et-e4rKnC-e4m8Zg-e4mcJV-qJCWSH">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

Robert Mercer, a Long Island hedge fund magnate, has made some lavish investments over the years: There’s his 203-foot super yacht, called the Sea Owl. There’s the $2 million model train set he had custom-built in his mansion—and the lawsuit he filed against the builders, saying they’d overcharged him.

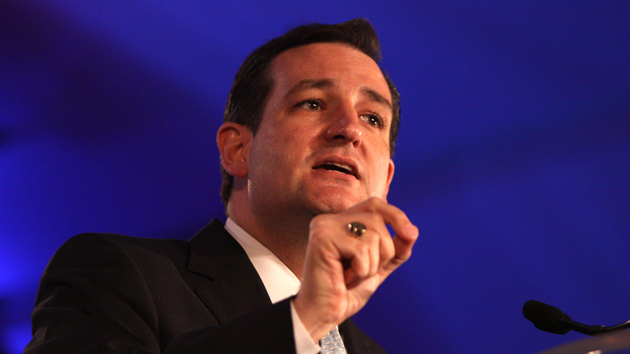

And now there’s the money he’s putting behind Ted Cruz’s presidential ambitions.

Mercer is the main bankroller of a ring of four super-PACs supporting Cruz for president, the New York Times reported Friday. The PACs have collected $31 million in the four weeks since Cruz launched his campaign, giving the freshman Senator’s bid for the Republican nomination a powerful start.

This is not Mercer’s first foray into campaign finance. As Mother Jones previously reported, Mercer is a longtime Republican donor who shares Cruz’s disdain for financial regulation. He has plowed millions into campaigns against lawmakers who have pushed to rein in Wall Street. Rep. Pete DeFazio (D–Ore.), who started an effort to tax high-frequency financial transactions, was the target of a Mercer campaign of more than half-a-million dollars. So was former Rep. Timothy Bishop (D–N.Y.), an ex-SEC prosecutor. In 2012, Mercer shoveled more than $900,000 into an effort to unseat Bishop. While Bishop held onto his seat, Mercer targeted him again in 2014—this time, with success. Also in 2012, Mercer pumped millions into two super PACs, headed by Karl Rove, that flooded the airwaves with ads for Mitt Romney and Republican candidates for Congress. Club For Growth, a free-market focused super PAC, has notched more than a half million from Mercer, too.

Given Mercer’s views, it’s no wonder that he would back the GOP presidential candidate who has mused about abolishing the IRS. But Mercer has felt the sting of financial oversight professionally, too. As Mariah Blake reported for Mother Jones in 2014, for several years, federal agents had been scrutinizing Renaissance, the hedge fund Mercer runs along with a business partner, Peter Brown.

Last year, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations got in on the action. In a hearing with Renaissance executives, its members accused the fund of using complicated financial maneuvers to avoid an estimated $6 billion in taxes. As Blake reported:

Renaissance is notoriously secretive about its investment formula. But documents released by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in July offer some clues about the engine behind its growth. In 1999, Deutsche Bank—which did not respond to requests for comment—approached Renaissance and offered to package all of the Medallion fund’s investments into a portfolio, or “basket,” that was held in the bank’s name. Under this arrangement, Renaissance would still control the trades and reap all the profits (minus the bank’s generous fees). But it didn’t have to pay short-term capital gains taxes on the underlying assets, even if they were only held for a few hours or days. (Short-term gains are taxed at 39 percent for the highest earners; long-term gains are taxed at roughly half that rate.)

“Renaissance profited from this tax treatment by insisting on the fiction that it didn’t really own the stocks it traded—that the banks that Renaissance dealt with, did,” Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), the ranking Republican on the subcommittee, said during the recent hearing. “But, the fact is that Renaissance did all the trading, maintained full control over the account…and reaped all of the profits.”

The company has denied any wrongdoing and the IRS investigation is ongoing.

Despite his outsized giving, Mercer is described by those who know him as quiet and intensely private. But as Bradley Smith, a campaign finance expert, pointed out to the Times, his money will do plenty of talking for him: The cash “sends the message to other donors that Cruz is a serious guy…And that brings in other donors.”