Update, 8/5/15: The Justice Department has indicted Paul world operatives Dimitri Kesari, John Tate, and Jesse Benton on numerous charges including making false statements, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice in connection with the alleged scheme to payoff then-Iowa state senator Kent Sorenson for his endorsement of Ron Paul’s 2012 presidential bid. Read the indictment here.

On December 26, 2011, a week before Iowa’s first-in-the-nation presidential caucuses, an influential Republican state senator named Kent Sorenson and his wife, Shawnee, arrived at a steak house in Altoona, a suburb of Des Moines. A goateed Mr. Clean look-alike, Sorenson was a hot commodity. His deep ties to the state’s evangelical leaders and home-schooling activists made his endorsement highly sought after by GOP presidential hopefuls, particularly the second-tier contenders who had staked their campaigns on a strong Iowa showing. Sorenson had picked his horse early, signing on as Michele Bachmann’s Iowa chairman in June 2011—a coup for the Minnesota congresswoman’s upstart campaign.

Joining the Sorensons was a bespectacled political operative named Dimitri Kesari, the deputy campaign manager of Rep. Ron Paul’s 2012 presidential bid. As caucus day neared, Ron Paul’s campaign was surging in the polls but needed a late boost if he wanted to meet his goal of finishing in the top three.

That’s where Sorenson came in.

When the state senator left to use the restroom, Kesari produced a $25,000 check—drawn from the account of Designer Goldsmiths, a jewelry store run by his wife—and gave it to Shawnee Sorenson. Two days later, Kent Sorenson left a Bachmann campaign event, drove straight to a Ron Paul rally, and declared that he had defected.

As it turned out, Paul’s inner circle had been secretly negotiating for months to lure Sorenson away from the Bachmann campaign. In an October memo to Paul campaign manager John Tate, a Sorenson ally outlined the state senator’s demands, which included an $8,000-a-month payment for nearly a year, another $5,000-a-month check for a colleague of Sorenson’s, and a $100,000 donation to Sorenson’s political action committee. The memo explained that these payments would not only secure Sorenson’s support in the near term but also help to “build a major state-based movement that will involve far more people into a future Rand Paul presidential run.” Kesari’s $25,000 check, in other words, amounted to more than a down payment on an endorsement for Ron Paul; it was an investment in Rand Paul 2016.

The Kentucky senator officially declared his candidacy on Tuesday. With the 2016 Iowa caucuses nine months away, this scheme could become a liability for the latest Paul presidential enterprise. The Sorenson deal exploded into public view in 2013, thanks to a pair of whistleblowers from the Ron Paul and Bachmann campaigns, and the episode now hangs over Rand Paul and his inner circle like a dark cloud.

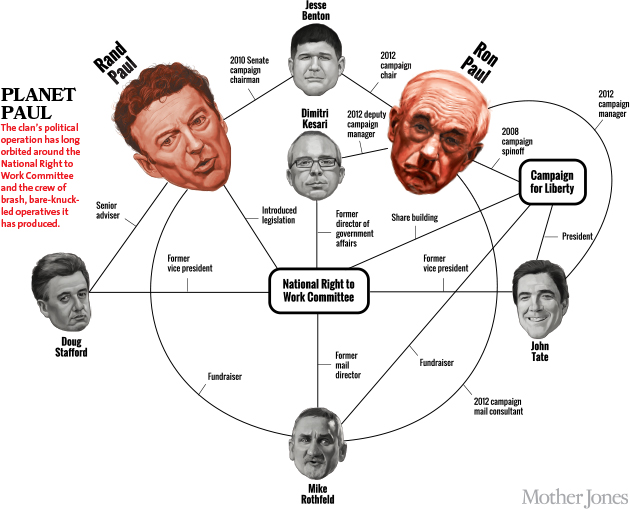

The Sorenson scandal has sparked state and federal investigations. After resigning his seat in 2013, Sorenson pleaded guilty last year to two criminal charges for which he faces up to 25 years in prison. The episode involves central figures in the Paul family’s political apparatus, including Kesari and Jesse Benton, who served in senior roles on Rand and Ron Paul’s recent campaigns. (Benton is also married to Ron Paul’s granddaughter and Rand’s niece.) And it has pulled back the curtain on the roguish band of advisers, political organizers, and fundraisers whose sometimes sketchy tactics have fueled Rand Paul’s political ascent. This crew—call it Paul World—reflects the damn-the-rules, libertarian worldview of the candidate himself. But as Paul may find out, the brash operatives largely responsible for his political rise could end up posing a major threat to his presidential ambitions.

“It’s a strange universe,” says a conservative strategist who’s well acquainted with members of the Pauls’ inner circle. “You’ve got the real Star Wars cantina identified—Hammerhead, Greedo—and let’s be honest, a lot of these guys would not have work in the mainstream, even in the tea party.”

Many of the central players in Paul World hail from the National Right to Work Committee, the leading anti-union group where these operatives spent their formative political years. Doug Stafford, who is Rand Paul’s Karl Rove, is a former NRTWC vice president. John Tate, Ron Paul’s former campaign manager, worked with Stafford at the NRTWC; he is now the president of Campaign for Liberty, the political group founded by the elder Paul. Kesari—described by someone who knows him as “like Radar from M*A*S*H“—previously led the NRTWC’s government affairs department. Mike Rothfeld headed the committee’s direct-mail operation in the late ’80s and early ’90s; he now runs the fundraising firm of choice for Rand Paul’s PAC, as well as the NRTWC and Campaign for Liberty.

Thanks in large part to this crew, Rand Paul has broken into the political mainstream, a feat never achieved by his father. But some of the operatives who have formed the backbone of his machine have at times thought little of stretching the rules to win elections and acquire power. And their past tactics may come back to haunt Paul during what could be the most important campaign of his political career.

Of the GOP‘s current presidential hopefuls, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker is most closely associated with an anti-union agenda, due to his 2011 law curbing collective bargaining for the state’s public-sector unions. But the Republican whose policy stances pose the most direct threat to labor is Rand Paul. In the eyes of the National Right to Work Committee, one former NRTWC staffer told me, “he is the golden child.”

After Paul was sworn into the Senate in 2011, one of the first pieces of legislation he cosponsored was the National Right-to-Work Act, the committee’s holy grail. The bill—also championed by Ron Paul—would make every state in the union a so-called right-to-work state and eviscerate organized labor as we know it. (Twenty-five states currently have such laws, banning unions from collecting dues from nonmembers to pay for representing those workers and bargaining on their behalf.) Since 2013, Paul has twice more introduced the legislation. (The bill never has gotten out of committee.)

He has frequently lent his name to NRTWC fundraising emails and petitions drumming up support for the bill and the group. Days after Paul took office, an NRTWC email blast went out under his name spelling out his intentions: “They snickered when I said I came to the US Senate to change Congress,” it reads. “But their laughter stopped when I sponsored the National Right to Work Act to free US workers from forced unionization and break Big Labor’s multi-billion dollar political machine forever.”

Paul has credited John Tate, a former NRTWC vice president, with playing a “crucial role” in assembling his 2010 Senate campaign, including introducing Paul to Stafford, now his closest adviser. NRTWC donated $7,500 to that campaign and deployed field staffers and other personnel to Kentucky to support Paul during his primary fight against establishment-backed Trey Grayson. In an email sent the day after Paul’s primary upset, an NRTWC staffer congratulated the committee’s field organizers: “What a week of History, and you get to say you were a part of it. Nice job!”

Just as the libertarian-leaning Pauls have worn the Republican label with unease, the 60-year-old NRTWC hasn’t always played well with the conservative movement or the GOP. (The mantra inside NRTWC, says an ex-staffer from the 1990s, was: “We’re Right-to-Work. We hate everybody.”) The group’s origins on the far right (its longest-serving president, Reed Larson, was affiliated with the John Birch Society) and fixation solely on defeating labor unions created a cultlike atmosphere in which even allies on the right were viewed with suspicion. “There has been a culture from the beginning of isolation and hyper-self-reliance,” says a former NRTWC senior staffer. “It’s the hermit kingdom of the conservative movement.”

Still, throughout the ’80s and ’90s, the committee gained respect for its brutally efficient political operation. It was one of the first outside groups to create an in-house phone bank to influence elections around the country, an operation that proved so successful that NRTWC spun it off into a stand-alone firm named Liberty Phone Center, Inc. Mike Rothfeld, a heavily caffeinated, hard-charging mentor to a generation of Virginia political consultants, cut his teeth running NRTWC’s direct-mail shop; he went on to form his own fundraising firm, Saber Communications, the Paul World’s go-to consultancy. (A born-again Southerner whose office features a mural of Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart, Rothfeld is no libertarian: He once referred to Ron Paul’s most die-hard supporters as “cwazy wabbits.”)

Over the years, NRTWC has served as a training ground for operatives drawn to the group’s zealous focus and its bare-knuckled style. Former staffers say NRTWC instilled a cutthroat, survival-of-the-fittest mentality in its employees. One former staffer from the 1990s recalls that the group hired nine people for only five or six positions, pitting the new hires against each other to see who came out on top. The group was also notorious for its low pay—until the early 2000s, midlevel staffers got less than $20,000 a year and worked overtime to eke out a living.

To earn extra cash, NRTWC staffers also moonlighted for political candidates who supported the right-to-work cause—a practice supported by the top brass—often spending lunch breaks and evenings helping candidates with their mail programs or fundraising pitches.

The near-religious devotion to the cause, the hard-ass attitude, and the freelancing all melded to create a win-at-all-costs approach that sometimes saw NRTWC, a tax-exempt nonprofit, disregard campaign laws banning outside groups from coordinating with candidates and officeholders. “They treated the rules as guidelines,” the ex-staffer from the ’90s says.

The circuitous path to the Kent Sorenson debacle leads, of all places, through a dilapidated meth house on the outskirts of Denver. That’s where boxes of files and bank records belonging to Western Tradition Partnership, an energy-company-funded Montana nonprofit created to fight environmentalists, were discovered and handed over to Montana’s Commissioner of Political Practices. As the commissioner later concluded, these files indicated that Western Tradition Partnership and its leader, an operative named Christian LeFer, had possibly broken the law by directly coordinating with candidates for Montana’s Legislature.

LeFer was a key cog in the right-to-work movement. Internal NRTWC emails depict him as the committee’s man on the ground in Montana, where, in addition to Western Tradition Partnership, he ran Montana Citizens for Right to Work. NRTWC funded LeFer’s group to the tune of $217,600 in 2010 and $56,500 in 2011, tax records show. After the meth house documents came to light, LeFer and his wife, Allison, sued to reclaim them, but a state judge dismissed their suit in October 2013, and the documents remained in the hands of a federal grand jury investigating Western Tradition Partnership.

Two thousand miles away, at his home in rural Virginia, a former NRTWC staffer and Ron Paul aide named Dennis Fusaro watched the drama unfolding in Montana with growing alarm. Fusaro knew all too well who LeFer was—in 2009 and 2010, Fusaro worked for NRTWC in Iowa and had been included on many email chains with LeFer. He feared the Montana investigation could spark a probe of NRTWC activities. Fusaro says he tried to bring his complaints to NRTWC leadership, but was rebuffed. (NRTWC did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

So, in what Fusaro says was an effort to save his own skin, he went public, eventually releasing to conservative bloggers a trove of emails, memos, and other records showing potentially illegal coordination between the NRTWC and a host of GOP candidates. But the biggest bombshell he dropped had to do with Kent Sorenson, whom Fusaro knew well from his days as an NRTWC operative in Iowa. Fusaro had been included on Paul campaign correspondence about securing Sorenson’s endorsement. Attached to one of those emails was the three-page memo outlining Sorenson’s demands for joining Ron Paul’s presidential campaign; its publication in August 2013 fueled the criminal investigation that eventually brought Sorenson down.

Fusaro’s documents also laid bare how NRTWC may have overstepped the rules banning outside groups from coordinating with political candidates. (We’ll spare you the legalese, but coordination is a campaign finance no-no because it provides a way to circumvent contribution limits to political campaigns.) Fusaro’s documents show NRTWC was involved in creating and sending out mailers on behalf of dozens of Republican candidates for the Iowa Legislature in 2010. Mailers ostensibly authored by candidates or their spouses were written on NRTWC computers and later approved by the candidates. In some cases, candidates instructed NRTWC on the mix of Republican and independent voters that should receive their mailers. Helping oversee this NRTWC mail program were two Paul World fixtures: Doug Stafford and Dimitri Kesari. (Stafford, emails obtained by Mother Jones show, also worked on Rand Paul’s 2010 Senate campaign while he was an NRTWC employee. Stafford declined to comment.)

Not only did Fusaro’s documents show evidence of coordination, but on their 2010 tax forms NRTWC and a Midwestern affiliate told the IRS they didn’t plan to get involved in any political work that year. Marcus Owens, a tax lawyer who from 1990 to 2000 ran the IRS division that oversees tax-exempt groups, says that filing false tax reports “could not only be a civil problem but a criminal one.”

While it is unclear whether Fusaro’s documents have prompted IRS scrutiny of NRTWC, they caused a world of hurt for Kent Sorenson. Nearly three years after his dramatic switch to the Ron Paul campaign, Sorenson pleaded guilty to covering up payments from both the Paul and Bachmann campaigns—her campaign was secretly paying him as well—and to obstructing an investigation into the payments. Sorenson never ultimately cashed Kesari’s jewelry store check, but he admitted to receiving payments totaling $73,000, which an Iowa Senate ethics investigation all but concluded came from the Paul campaign.

Had the Sorenson saga ended there, Rand Paul and his presidential team could probably breathe easy. But on February 19, a Justice Department lawyer requested a delay in sentencing Sorenson because the feds were “making progress” on a “larger investigation” into the scandal. This prompted conservative radio host Steve Deace to tweet: “Asteroid coming. Impact could produce potentially large blast radius.” The DOJ did not say who else was in its crosshairs, but emails and internal documents show that Benton and Kesari both played roles in the deal. Sorenson, for his part, isn’t holding anything back. “He’s cooperating and answering their questions about all the information that he knows,” says F. Montgomery Brown, Sorenson’s attorney.

In the meantime, Paul World has lawyered up. Ron Paul’s 2012 campaign has shelled out $364,000 in legal fees since August. Reached on his cellphone, Kesari said he wouldn’t comment and hung up; Benton and his lawyer did not respond to repeated interview requests. At least publicly, Rand Paul has said little to suggest he’s worried about the legal headaches that may ensnare Paul World fixtures. In December—before the Justice Department’s latest announcement but after emails showed Jesse Benton’s involvement in the Sorenson deal, prompting Benton’s resignation as Sen. Mitch McConnell’s 2014 campaign manager—Paul defended Benton to the Hill newspaper as an “honest” political operative who would be “welcome” on his 2016 team. “He’ll help us,” Paul said.

But as Rand Paul launches his presidential campaign, questions linger about how long his cadre of advisers and operatives will last under the merciless glare of the national stage. “They are in such a bubble in this Rand Paul universe, and I think the bubble’s going to pop real quick in the heat of the primaries,” says the conservative strategist familiar with the Pauls and their allies. “They are not ready for prime time.”