Once again, the Obama administration has set its sights on American companies that stash untaxed revenue abroad. Its 2016 budget, unveiled earlier this week, proposes to stick a one-time “transition toll charge” of 14 percent on the more than $2 trillion in corporate earnings parked overseas, regardless of whether they’re brought back stateside. The estimated $280 billion in tax revenue would be earmarked for upgrading highways and infrastructure.

The proposed one-time tax is aimed at just one of the various loopholes and maneuvers that domestic businesses use to offshore their profits, beyond the reach of Internal Revenue Service. The best known trick is so-called tax inversions: US companies can move their headquarters abroad, avoiding the taxman while keeping executives stateside, scoring government contracts, and taking full advantage of public benefits for employees. Walgreens, which makes a quarter of its money from Medicaid and Medicare, proposed moving to Switzerland last year, only to change plans following a public outcry.

With business as usual, inversions could cost nearly $20 billion in runaway taxes over the next 10 years. President Obama has slammed inversions, yet Congress looks unlikely to touch the maneuver anytime soon. While business groups have balked at the White House’s latest international tax proposal, some Republicans have said they’ll consider it. Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) even called it “constructive.”

A look at how US companies take their money and run—for the border:

Foreign Affairs

Inversions aren’t the only way to dodge the taxman. Foreign profits aren’t taxed until they are “repatriated,” so companies can hoard earnings in subsidiaries or divisions abroad. (Ireland just shut down the “double Irish” offshoring trick used by Apple, Google, Twitter, and Facebook.) Between 2008 and 2013, American firms held more than $2.1 trillion in profits overseas—that’s as much as $500 billion in unpaid taxes.

Accumulated offshore profits at end of 2013:

|

General Electric: $110 billion |

|

Microsoft: $76.4 billion |

|

Pfizer: $69 billion |

|

Apple: $54.4 billion |

|

Exxon Mobil: $48 billion |

|

Citigroup: $43.8 billion |

|

Google: $38.9 billion |

|

Goldman Sachs: $22 billion |

|

Walmart: $19 billion |

|

McDonald’s: $16 billion |

Over There

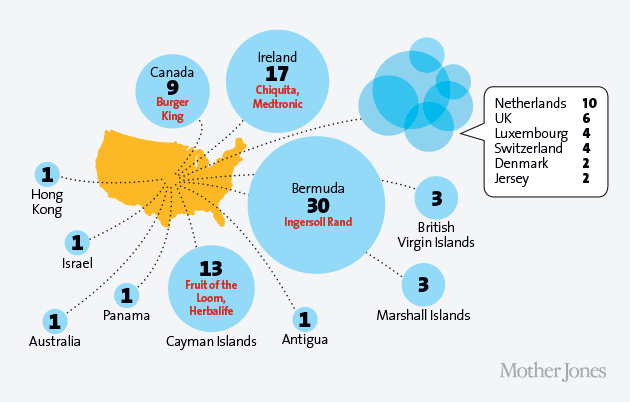

More than 100 companies have renounced their US citizenship since 1983, most in the past decade. Where they’ve gone:

A Man, a Plan, an Inversion

Tax inversion was pioneered in 1983, when the construction company McDermott International changed its address to Panama to avoid paying more than $200 million in taxes. The tax lawyer who masterminded the “Panama Scoot” was later immortalized in an operetta performed for his colleagues. (Big hat tip to Businessweek for tracking it down.) Sample verse:

The feds will be screaming,

But you will be beaming

‘Cause we’ll never pay taxes,

We’ll never pay taxes,

Never pay taxes again!

Have It Your Way, Eh

Last year, Burger King obtained the Canadian doughnut chain Tim Hortons and announced plans to move its HQ to the Great White North. Here’s what the fast-food giant stands to gain:

|

Avoiding $400 million to $1.2 billion in US taxes over the next four years. |

|

Major shareholders could avoid as much as $820 million in capital-gains taxes. |

|

Its low-wage employees would still receive more than $350 million in federal benefits and tax credits. |

There’s No Place Like Home

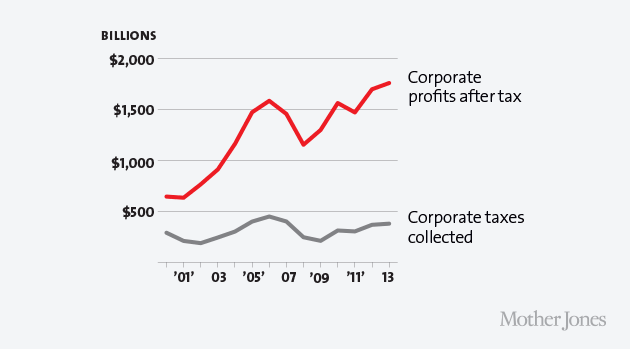

Few big companies actually pay the 35 percent corporate tax rate. Profits are up 21 percent since 2007, while corporate America’s total tax bill has dropped 5 percent.

Wings icon by James Cottell/The Noun Project; money bag icon by gira Park/The Noun Project