Ron Sachs/ZUMA

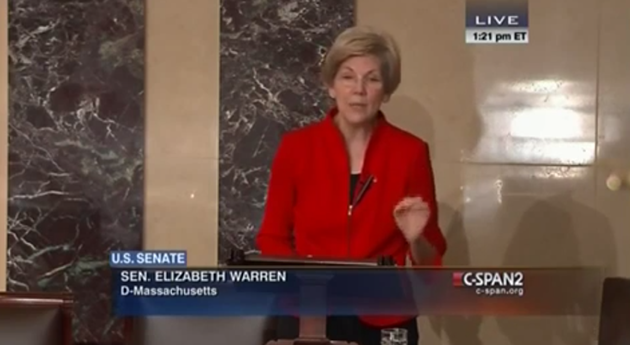

On Tuesday evening, lawmakers released the text of the massive spending bill that Congress must approve to avoid a government shutdown. Buried on page 615 of that 1,603-page piece of legislation is a provision entirely unrelated to government funding that a few lawmakers managed to sneak into the bill without any public debate during last-minute negotiations. It’s a Wall Street giveaway—written by Citigroup—that would allow banks to engage in more types of risky trading with taxpayer-backed money. Progressive Democrats and their allies have since launched an all-out campaign to strike the Citi-written provision from the spending bill. Elizabeth Warren railed against the provision on the Senate floor Thursday afternoon, warning, “A vote for this bill is a vote for taxpayer bailouts of Wall Street.” As of Thursday afternoon, it was unclear whether House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) could secure enough votes to pass the spending bill containing this measure and send it to the Senate. (Update: The bill passed the House.)

Here are the problems with the Citigroup-drafted provision, according to Michael Greenberger, a former derivatives regulator at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission who is now a law professor at the University of Maryland.

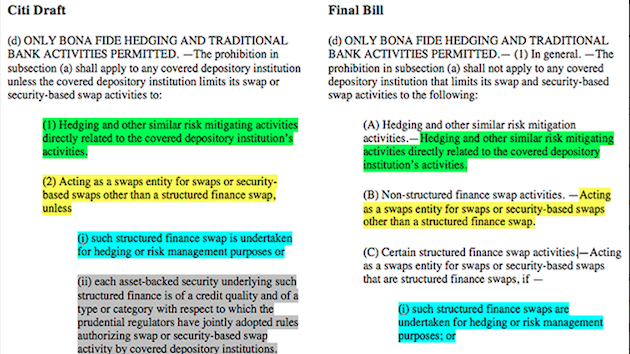

What is so bad about this provision? If Congress okays this measure, taxpayers could be on the hook in the event of another financial crisis. This provision guts the so-called push-out rule created by the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform act. This rule forbids banks from trading certain derivatives—complicated financial instruments with values derived from underlying variables, such as crop prices or interest rates. Instead, banks would have to shift these high-risk trades into separate nonbank affiliates that aren’t insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and are less likely to receive taxpayer bailouts. If the Citi-written measure becomes law, the largest FDIC-insured banks in the country will be able to make a wider range of these risky trades.

What will happen if there’s another financial crisis? If there’s an economic downturn triggered by derivatives trading gone bad, banks will be able to count on a taxpayer bailout—just like they received in 2008. “It’s very dangerous,” Greenberger says. “If [banks] lose on this type of trading and that causes a disruption in the markets, the taxpayer will be confronted with whether to let the banks fail or bail them out to the tune of trillions of dollars.”

Could taxpayers be at risk even in boom times? Yep. In 2012, JPMorgan Chase lost $6 billion on a bad trade that has come to be known as the London Whale. “JPMorgan was essentially gambling with FDIC-insured money, secure in the knowledge that major losses would be borne by the public while profits would stay in the bank,” David Dayan wrote in Salon last year. JPMorgan, it turned out, was able to withstand that loss without a bailout, but a lot of other US banks couldn’t, Greenberger explains: “You could have a trade that loses a lot more than $6 billion by a rogue trader, in which case taxpayers have to foot the bill.”

How were lawmakers able to sneak this into the big appropriations bill? It’s common for lawmakers to force bills through Congress by attaching them to larger must-pass legislation. The practice is part of the wheeling and dealing that allows Republicans and Democrats to come to agreement on major legislation. But, Greenberger says, “putting these substantive provisions in appropriations bills is very, very dangerous stuff…If you want a controversial provision in there that you couldn’t get in under regular order, this is the way to do it.” He adds, “Then the president has problems vetoing it because the government will shut down. It’s a bad way to do business.”

If Congress approves this measure, what does it mean for economic populism? “Economic populism is alive and well,” Greenberger maintains. “It’s just that nobody in leadership wants to take advantage of it, whether they’re Republican or Democrat.” Lawmakers from both sides of the aisle worked to push the Citi-written provision into the spending bill.