Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.)<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&searchterm=bad%20math&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=149938643">alphaspirit</a>/Shutterstock

Update, Wednesday, January 7, 2015: On Tuesday, the House implemented dynamic scoring. The Senate is expected to follow suit.

When Republicans took control of both houses of Congress earlier this month, they won an important new power: They can change how Congress does math.

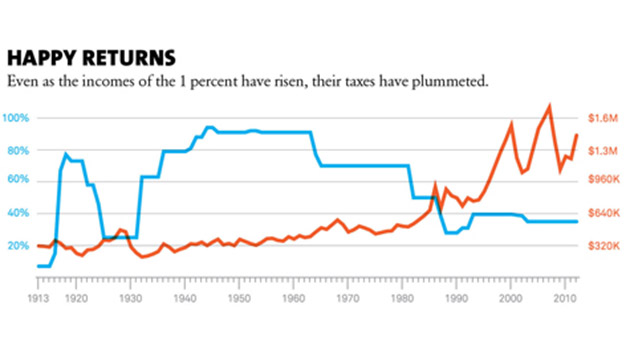

Seriously. Republicans, led by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), their budget guru, are considering altering the way Congress calculates the costs of tax cuts—a move that could make big tax cuts for the rich appear less costly than they really are.

Here’s how it would work. In January, Republicans will be in charge of Congress. And that includes the Joint Committee on Taxation, which calculates how tax laws affect revenue, and the Congressional Budget Office, which produces official budget projections. Right now, when the CBO and the JCT calculate the impact of tax laws on government income, they consider how Americans might alter their behavior in response to tax rate changes. But these tax-math bodies do not evaluate how tax legislation could affect economic growth—largely because those sorts of impacts are hard to predict. Republicans have long claimed that tax cuts lead to greater economic activity that inexorably yields more tax revenues—a point much disputed. But Ryan, who in January will head up the House Ways and Means committee (which has jurisdiction over tax reform), and his fellow GOPers are looking to enshrine this Republican belief into the hard and fast calculations of Capitol Hill’s number-crunchers.

Last week, in an interview with the Washington Post, Ryan said he will push to make sure that the two congressional budget scorekeepers use this accounting method—known as “dynamic scoring”—when evaluating GOP tax reform legislation. Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), who will chair the Senate finance committee starting in January, said last week that he was open to implementing the change.

Ryan and Hatch can implement dynamic scoring by simply ordering the two budget scorekeepers to accept this budgeting method. Not only that, Republicans can require the CBO and JCT to use very optimistic assumptions about how tax cuts affect the economy—that is, how tax cuts influence people’s motivation to work, the moves of the Federal Reserve, and household and business decisions on savings and investment. Budget analysts then can plug those assumptions into several models estimating economic growth, and GOPers will be able to cherry-pick the model that produces the best numbers for them. “The risk is that a Congress that is politically motivated takes the most unrealistic models and plugs in highly rosy assumptions,” says Chye-Ching Huang, a budget expert at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

If Republican legislators don’t want to intervene directly in the JCT’s and CBO’s calculations, they have another option: They can install directors at the CBO and JCT who will use the kind of assumptions the GOP favors. Neither congressional Dems nor President Barack Obama can prevent that.

Republicans have pushed for this budget-math readjustment since the Reagan days. And for years, policy wonks have debated the merits of dynamic scoring. Kenneth Kies, a GOP-nominated former director of the JCT, told the Washington Examiner last week that this accounting device falls “somewhere between pure mathematics and theology.” Because this arcane tweak can make tax cuts for the wealthy appear to cost the government less than they actually do, it is extremely appealing to Republicans. If they make this change, they could argue that new tax cuts for the well-to-do would partly pay for themselves—and wave the JCT-CBO seal of approval to justify their claim. Democrats contend that dynamic scoring is a gimmick designed to allow Republicans to chop taxes for the rich without paying the political cost.

Ryan’s office did not respond to a request for comment.