Liberian President Ellen Johnson SirleafJerome Delay/AP

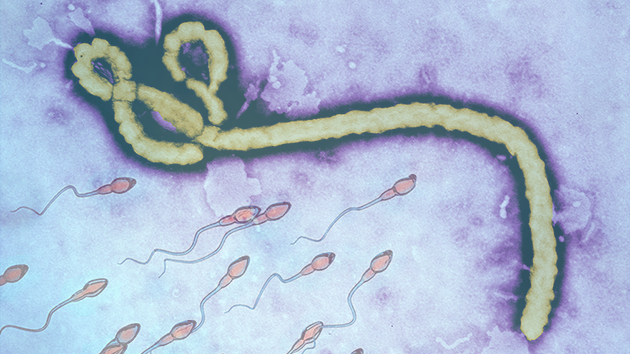

Ebola has already claimed the lives of more than 2,000 people in Liberia. Now, the Liberian president’s critics are warning that her response to the epidemic is threatening to undermine the country’s fragile democratic institutions.

The controversy began back on August 6 when President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf announced a 90-day state of emergency to deal with the crisis. More recently, Sirleaf wrote a letter to the national legislature requesting the legal authority to suspend a number of civil liberties guaranteed by the country’s constitution. If enacted, the measures would give Sirleaf the power to restrict the movement of certain communities by proclamation and even to limit speech that could create “false alarm.” The government would also be able to confiscate private property “without payment of any kind or any further judicial process” in order to protect the public’s health.

The Liberian House of Representatives rejected the proposals in a landslide vote, but the Senate was still debating them as of yesterday.

Even if the Liberian legislature votes against Sirleaf’s request for more power, the government has already taken actions that erode civil liberties in the name of fighting the disease.

Since declaring a state of emergency, Sirleaf’s government has introduced a nationwide curfew, forcing people to stay indoors at night. Against the advice of Ebola experts and Liberian health officials, Sirleaf also ordered the quarantine of an entire slum in Monrovia in an attempt to contain an outbreak in the Liberian capital. (The slum was reopened 10 days later.) This month—with the legislature’s backing—Sirleaf suspended a special Senate election, citing a lack of essential staff and materials.

Press freedoms have also been eroded: When the curfew was first announced, journalists were not included on a list of exempted professions able to move freely around the country at night. (They were added six days later.) In early October, citing privacy concerns, the government announced that reporters could be arrested for speaking with Ebola patients or photographing treatment centers without written permission from the health ministry.

In her recent letter to the legislature, Sirleaf asked for the authority to further restrict freedom of the press. “Because falsehood and negative reporting on the state of the affairs is likely to defeat the national effort in the fight of the Ebola virus, it is important that such be discouraged and prevented,” she wrote. “Accordingly, the Government of Liberia will restrict speeches that will confuse the citizens and residents including the raising of false alarm thereby creating fear during the state of emergency.”

The rule of law has never been strong in Liberia. Almost from its inception, the country was governed by oppressive regimes. But by the time its 14-year civil war ended in 2003, nascent democratic institutions began to take shape. In its latest ratings, the democracy watchdog Freedom House classified Liberia as “partly free.”

Now, some fear, Sirleaf’s proposals are moving the country back in the direction of authoritarian rule.

“In my view, this is dangerous, and it reminds us of the days when the dictators govern Liberia,” Acarous Gray, a member of the Liberian House of Representatives, told the US-funded news agency Voice of America.

Roosevelt Woods, executive director for the Foundation for International Dignity, a Liberian human rights advocacy group, also slammed the president for overreaching. “This is dangerous for our country,” he told a group of journalists last weekend. “Anything that has to do with absolute power that violates human rights is a bad sign for Liberia. [Sirleaf] was elected to bring positive change, to restore hopes and not to dash them.”

The news also poses a dilemma for the United States, which has been one of the most active partners in aiding Liberia’s democratic transition. Over the past decade, the US Agency for International Development spent $271 million on democracy and governance programs in the country—almost a quarter of all its aid to Liberia during that time, according to an agency report.

Because it was dealing with such a weak state, USAID looked for ways to build up Liberia’s capacity to govern itself, while simultaneously trying to develop measures to ensure the government respected its citizens’ basic rights. The strategy USAID chose was to help strengthen the country’s historically abusive executive branch while also training local media and community-based organizations to report on corruption and better inform the public. But that approach has potential drawbacks. “The risk…is that we put too much emphasis on governance and too little on democratic governance,” the agency acknowledged in its report.

Now, with the Ebola response threatening some core freedoms, the agency says it’s up to Liberians to determine how far Sirleaf can go. “Whether and how any steps are taken to restrict any of these rights is an issue for discussion among Liberia’s three branches of government, and between the government and civil society,” a USAID spokesperson said in a statement to Mother Jones. “We hope it will not be necessary for President Sirleaf to take steps to restrict civil liberties.”

But Liberian authorities have already done just that—especially in their dealings with the press. In August, the government used tear gas to shutter the National Chronicle newspaper just hours after the information minister threatened reporters critical of the government’s response to the crisis. (The Chronicle had recently published a series of stories discussing efforts by Sirleaf’s rivals to challenge her government.) Days later, the editor of the Women Voices newspaper reported being harassed and interrogated by police after publishing a story alleging that law enforcement officials had misused funds intended for the Ebola effort.

Free press advocates have expressed concern over the recent developments. “Liberia’s public health crisis must not be used as a pretext for cracking down on the media,” Virginie Dangles, assistant research director for Reporters Without Borders, said in a statement. “On the contrary, the media need to be involved as much as possible, to provide the population with constant information about the state of the epidemic, the government’s response and the preventive measures being adopted.”

The Chronicle and Women Voices incidents and others were detailed in a letter from the Press Union of Liberia to Justice Minister Christiana Tah on September 4. She won’t be able to do anything about it now, however. Tah resigned on October 6, accusing the president of undermining the independence of her office.

“The investments of national and international stakeholders promoting the rule of law [are] being eroded by actions that contradict the values that underpin the fabric of our society,” she wrote in her letter of resignation.